1.3: Moments

- Page ID

- 50570

A moment (also sometimes called a torque) is defined as the "tendency of a force to rotate a body". Where forces cause linear accelerations, moments cause angular accelerations. In this way moments, can be thought of as twisting forces.

The Vector Representation of a Moment:

Moments, like forces, can be represented as vectors and have a magnitude, a direction, and a "point of application". For moments however a better name for the point of application is the axis of rotation. This will be the point or axis about which we will determine all the moments.

Magnitude:

The magnitude of a moment is the degree to which the moment will cause angular acceleration in the body it is acting on. It is represented by a scalar (a single number). The magnitude of the moment can be thought of as the strength of the twisting force exerted on the body. When a moment is represented as a vector, the magnitude of the moment is usually explicitly labeled. though the length of the moment vector also often corresponds to the relative magnitude of the moment.

The magnitude of the moment is measured in units of force times distance. The standard metric units for the magnitude of moments are Newton-meters, and the standard English units for a moment are foot-pounds.

\[ M = F * d \]

\[ \text{Metric:} \,\, N * m \]

\[ \text{English:} \,\, lb * ft \]

Direction:

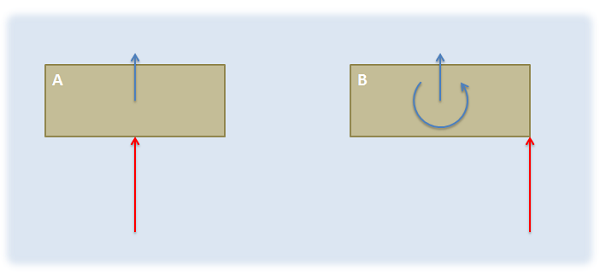

In a two-dimensional problem, the direction can be thought of as a scalar quantity corresponding to the direction of rotation the moment would cause. A moment that would cause a counterclockwise rotation is a positive moment, and a moment that would cause a clockwise rotation is a negative moment.

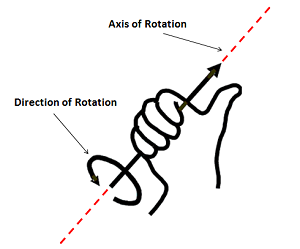

In a three-dimensional problem, however, a body can rotate about an axis in any direction. If this is the case, we need a vector to represent the direction of the moment. The direction of the moment vector will line up with the axis of rotation that moment would cause, but to determine which of the two directions we can use along that axis we have available we use the right hand rule. To use the right hand rule, align your right hand as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) so that your thumb lines up with the axis of rotation for the moment and your curled fingers point in the direction of rotation for your moment. If you do this, your thumb will be pointing in the direction of the moment vector.

If we look back to two-dimensional problems, all rotations occur about an axis pointing directly into or out of the page (the \(z\)-axis). Using the right hand rule, counterclockwise rotations are represented by a vector in the positive \(z\) direction and clockwise rotations are represented by a vector in the negative \(z\) direction.

Axis of Rotation:

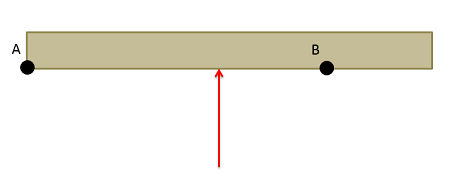

In engineering statics problems we can choose any point/axis as the axis of rotation. However, the choice of this point will affect the magnitude and direction of the resulting moment, and the moment is only valid about that point.

Though we can take the moment about any point in a statics problem, if we are adding together the moments from multiple forces, all the moments must be taken about a common axis of rotation. Moments taken about different points cannot be added together to find a "net moment."

Additionally, if we move into the subject of dynamics, where bodies are moving, we will want to relate moments to angular accelerations. For this to work, either we will need to take the moments about a single point that does not move (such as the hinge on a door) or we will need to take the moments about the center of mass of the body. Summing moments about other axes of rotation will not result in valid calculations.

Calculating Moments:

To calculate the moment that a force exerts on a body, we will have two main options: scalar methods and vector methods. Scalar methods are generally faster for two-dimensional problems where a body can only rotate clockwise or counterclockwise, while vector methods are generally faster for three-dimensional problems where the axis of rotation is more complex.