10.2.3: 3 Herbicide Resistance

- Page ID

- 48525

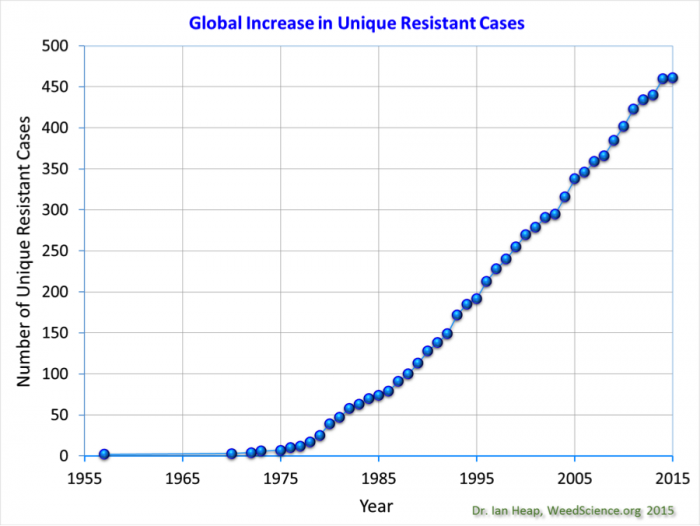

Although integrated pest management was introduced in the 1980s, the number of weeds that have evolved resistance to new herbicides continues to grow (See Figure 8.2.8 below).

Figure 8.2.8.: Global Increases in Unique Resistant Cases. Credit: Dr. Ian Heap, International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds

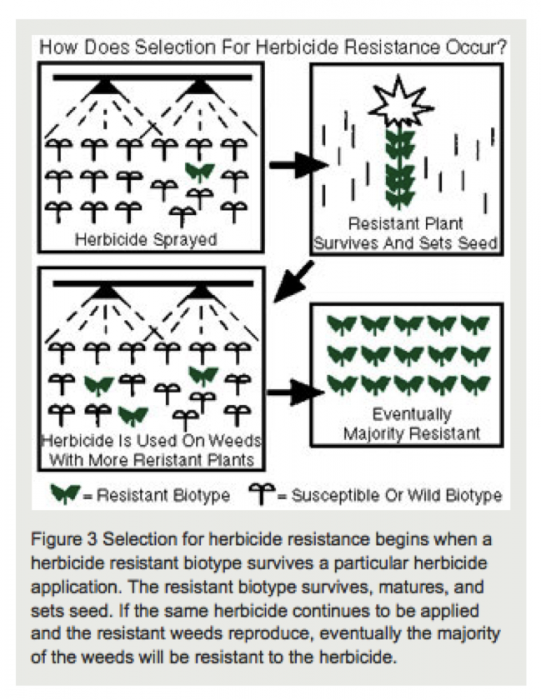

Similar to other pests, weeds evolve resistance when exposed to the same strong selective force, such as an application of the same herbicide over consecutive years. When the same herbicide is applied numerous times to a field, susceptible weeds are killed, leaving resistant individuals to reproduce and dominate the population, as illustrated in figure 8.2.9 below.

Figure 8.2.9.: Selection for herbicide resistance begins when an herbicide resistant biotype survives a particular herbicide application. The resistant biotype survives, matures, and sets seed. If the same herbicide continues to be applied and the resistant weeds reproduce, eventually the majority of the weeks will be resistant to the herbicide. Credit: J. L. Gunsolus. Weed Science, Department of Agronomy and Plant Genetics. Herbicide-resistant weeds.

Integrated Weed Management

Integrated weed management (IWM) is an IPM approach for weeds that can provide long-term weed control of weeds by integrating multiple control strategies. Some weed scientists have described IWM as utilizing “many little hammers” as opposed to continuously employing one “big hammer” such as an herbicide (Liebman & Gallandt, 1997). Weed control tactics fall into the IPM control categories that you learned about for insect control in Module 8.1. Examples of weed control practices include the following:

- Cultural control practices are management practices humans can employ to prevent weed establishment and maintain vigorous crop growth. Examples include: crop rotation with crops of different life cycles and seeding densities, planting certified seed that is managed to have minimal weed contamination, planting adapted crop varieties, adjusting row spacing, population density, and timing for a competitive crop and successful crop establishment, maintaining soil health and fertility, and using practices that prevent weed establishment such as cover crops and mulching.

Figure 8.2.10.: Straw mulch to suppress weeds in garlic. Credit: Heather Karsten

Figure 8.2.11.: Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum L. ) cover crop planted mid-season to smother weeds, produce organic matter and provide habitat for beneficial insects. Credit: Anna Santini

Figure 8.2.12.: Crop rotation of summer annual row crops such as corn (first photo) with densely seeded perennial alfalfa (second photo), and/or densely planted winter annual wheat and spring oats (third photo, wheat is on the right, oats are on the left). Credit: Heather Karsten

- Mechanical or physical weed control includes practices such as plowing, cultivation, hoeing, targeted hand-weeding, and flaming.

Figure 8.2.13.: This flex tine cultivator is used to control weeds when they are very small. Credit: Heather Karsten

Figure 8.2.14.: Rotary harrow for weed cultivation. Credit: Heather Karsten

- Biological control: conserving or introducing herbivorous insects, grazing or browsing animals, or plant pathogens to reduce weed populations. Biological control of weeds is typically used on extensive rangeland where other more labor intensive or expensive methods are not cost effective.

- Chemical control: the application of herbicides, or the use of herbicide-resistant crops with herbicide applications to control weeds

- Genetic resistance: selecting crop varieties that are well adapted to an environment and competitive with weeds. Herbicide-resistant crops may also be considered a form of genetic resistance.