16.4: The Queue ADT

- Page ID

- 15164

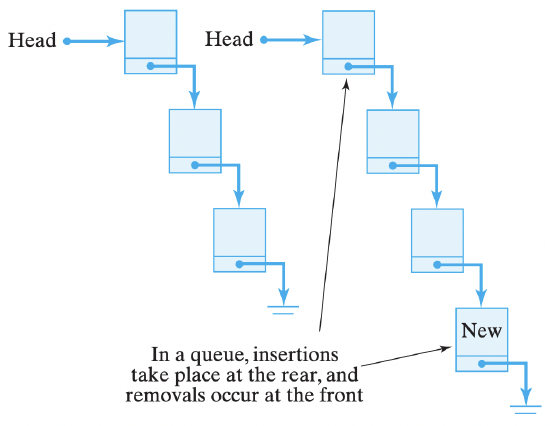

A queue is a special type of list that limits insertions to the end of the list and removals to the front of the list. Therefore, it enforces first-in–first-out (FIFO) behavior on the list. Think of the waiting line at the salad bar. You enter the line at the rear and you leave the line at the front (Fig. 16.24).

The queue operations are conventionally called enqueue, for insert, and dequeue, for remove, respectively. Thus, the queue ADT stores a list of data and supports the following operations:

- Enqueue—insert an object onto the rear of the list.

- Dequeue—remove the object at the front of the list.

- Empty—return true if the queue is empty.

Queues are useful for a number of computing tasks. For example, the ready, waiting, and blocked queues used by the CPU scheduler all use a FIFO protocol. Queues are also useful in implementing certain kinds of simulations. For example, the waiting line at a bank or a bakery can be modeled using a queue.

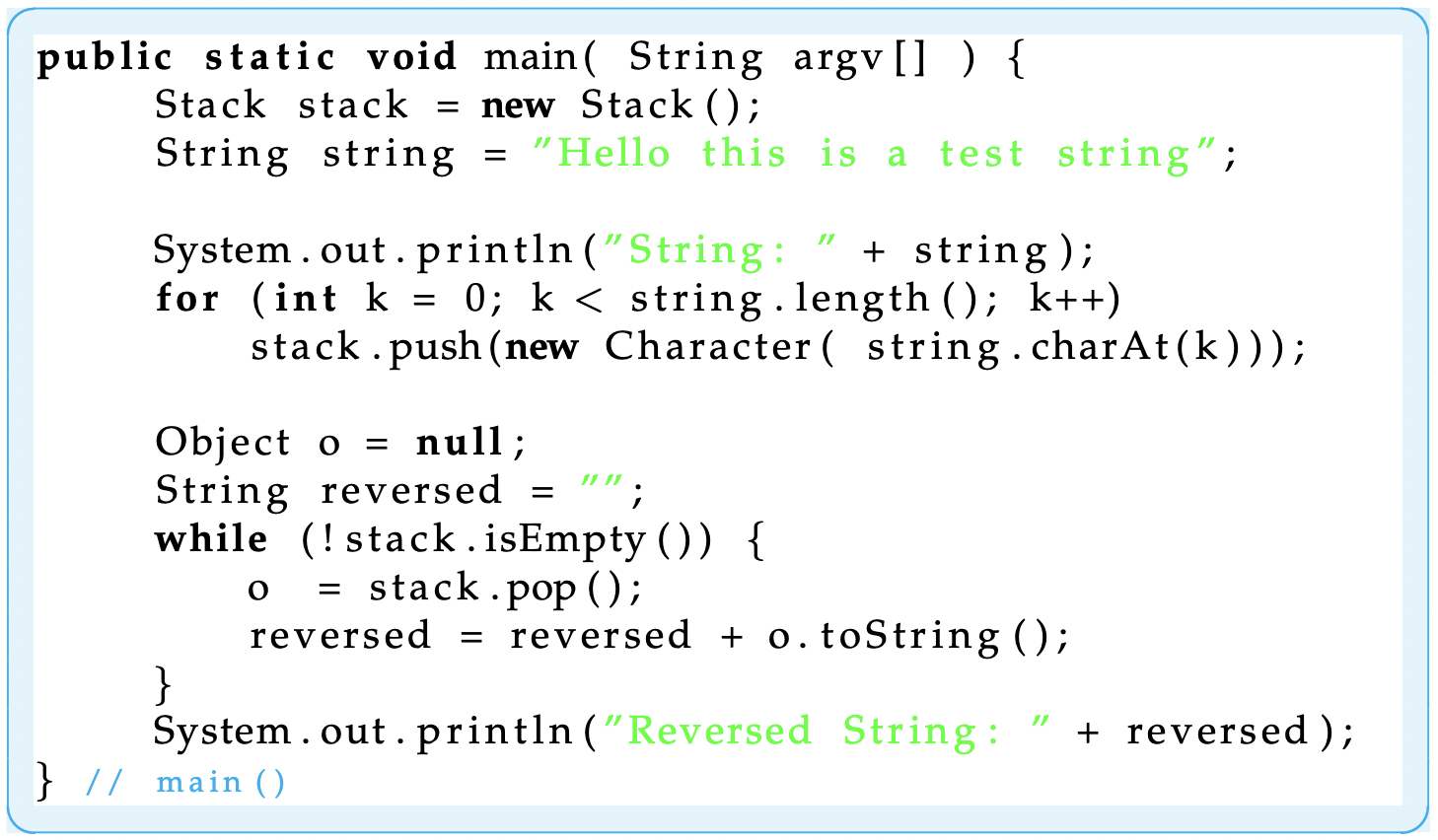

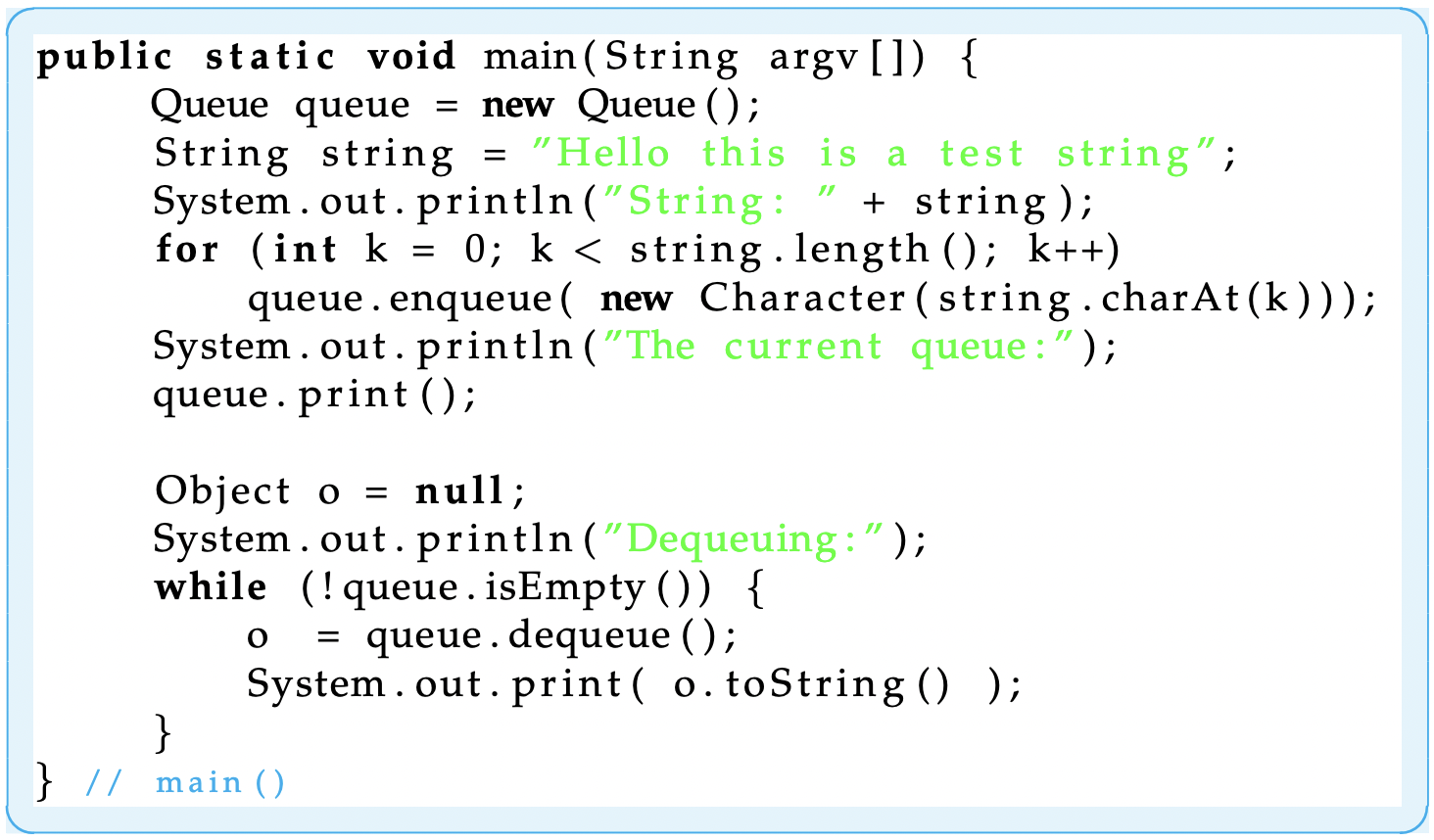

Figure 16.23: A method to test the

Figure 16.23: A method to test the Stack ADT, which is used here to reverse a String of letters. queue is a list that permits insertions at the rear and removals at the front only.

queue is a list that permits insertions at the rear and removals at the front only.16.4.1 The Queue Class

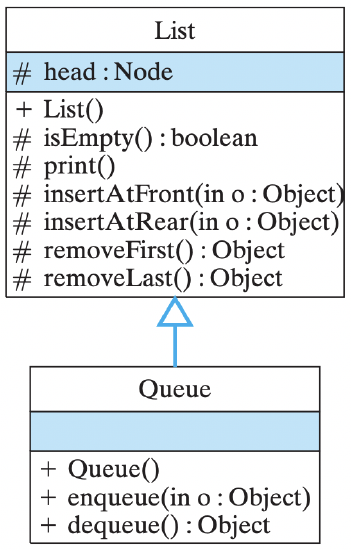

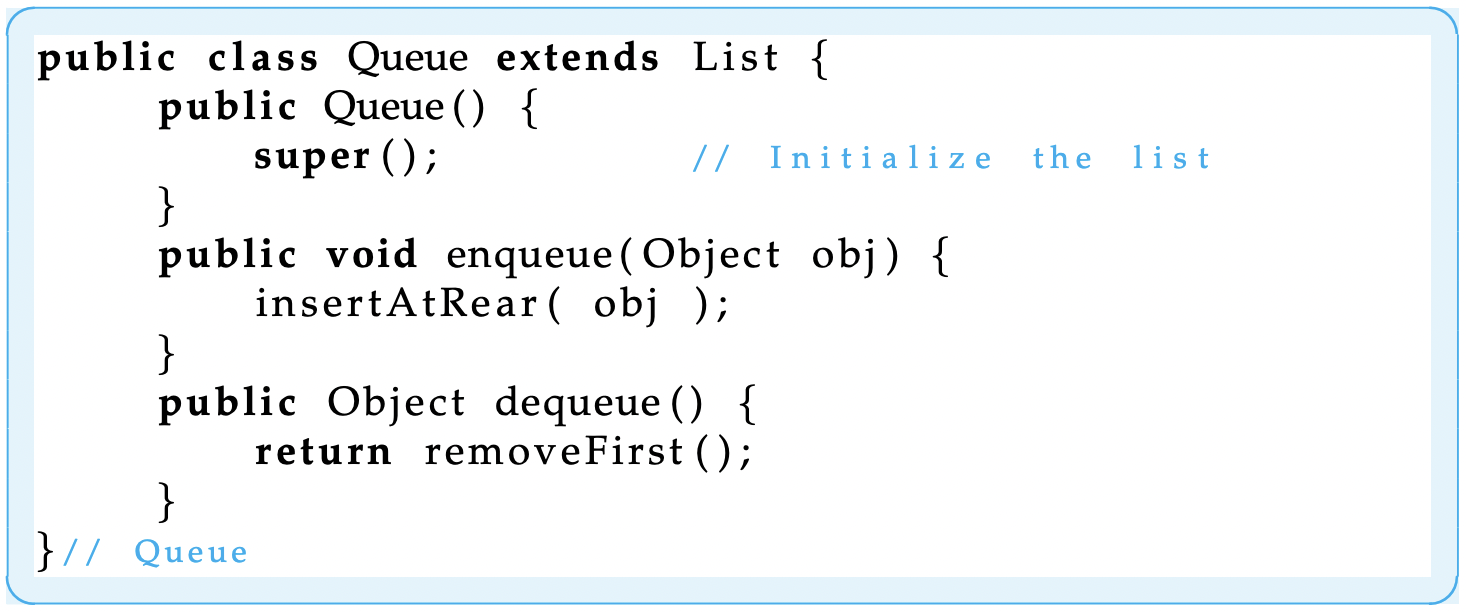

Figure 16.25: The Queue’s enqueue() and dequeue() methods can use the List’s insertAtRear() and removeFirst() methods, respectively.

Figure 16.26: The Queue ADT.

Figure 16.27: A method to test the Queue ADT. Letters inserted in a queue come out in the same order they went in.

JAVA EFFECTIVE DESIGN

ADTs.

ADTs encapsulate and manage the difficult tasks involved in manipulating the data structure. But because of their extensibility, they can be used in a wide range of applications.

SELF-STUDY EXERCISE

Exercise 16.10

Define a peekLast() method for the Queue class. It should take no parameters and return an Object. It should return a reference to the Object stored in the last Node of the list without removing it.

Special Topic: The LISP Language

One of the very earliest computer languages, and the one that’s most often associated with artificial intelligence (AI), is LISP, which stands for LISt Processor. LISP has been, and still is, used to build programs for human learning, natural language processing, chess playing, human vision processing, and a wide range of other applications.

The earliest (pure) versions of LISP had no control structures and the only data structure they contained was the list structure. Repetition in the language was done by recursion. Lists are used for everything in LISP, including LISP programs themselves. LISP’s unique syntax is simple. A LISP program consists of symbols, such as 5 and x, and lists of symbols, such as (5), (1 2 3 4 5), and ((this 5) (that 10)), where a list is anything enclosed within parentheses. The null list is represented by ().

Programs in LISP are like mathematical functions. For example, here’s a definition of a function that computes the square of two numbers:

( define (square x) (∗ x x))

The expression (square x) is a list giving the name of the function and its parameter. The expression (* x x) gives the body of the function.

LISP uses prefix notation, in which the operator is the first symbol in the expression, as in (* x x). This is equivalent to (x * x) in Java’s infix notation, where the operator occurs between the two operands. To run this program, you would simply input an expression like (square 25) to the LISP interpreter, and it would evaluate it to 625.

LISP provides three basic list operators. The expression (car x) returns the first element of the (nonempty) list x. The expression (cdr x) returns the tail of the list x. Finally, (cons z x) constructs a list by making z the head of the list and x its tail. For example, if x is the list (1 3 5), then (car x) is 1, (cdr x) is (3 5), and (cons 7 x) is (7 1 3 5).

Given these basic list operators, it is practically trivial to define a stack in LISP:

(define (push x stack) (cons x stack))

(define (pop stack) (setf stack(cdr stack)) (car stack))

The push operation creates a new stack by forming the cons of the element x and the previous version of the stack. The pop operation returns the car of the stack but first changes the stack (using setf) to the tail of the original stack.

These simple examples show that you can do an awful lot of computation using just a simple list structure. The success of LISP, particularly its success as an AI language, shows the great power and generality inherent in recursion and lists.