15.7: Common Hilbert Spaces

- Page ID

- 23197

Common Hilbert Spaces

Below we will look at the four most common Hilbert spaces (Section 15.4) that you will have to deal with when discussing and manipulating signals and systems.

\(\mathbb{R}^n\) (real scalars) and \(\mathbb{C}^n\) (complex scalars), also called \(\ell^{2}([0, n-1])\)

\(\boldsymbol{x}=\left(\begin{array}{c}

x_{0} \\

x_{1} \\

\dots \\

x_{n-1}

\end{array}\right)\) is a list of numbers (finite sequence). The inner product (Section 15.4) for our two spaces are as follows:

- Standard inner product \(\mathbb{R}^n\):

\begin{align}

\langle\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle &=\boldsymbol{y}^{T} \boldsymbol{x} \nonumber \\

&=\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} x_{i} y_{i}

\end{align} - Standard inner product \(\mathbb{C}^n\):

\[\begin{align}

\langle\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle &=\overline{\boldsymbol{y}^{T}} \boldsymbol{x} \nonumber \\

&=\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} x_{i} \bar{y}_{i}

\end{align} \nonumber \]

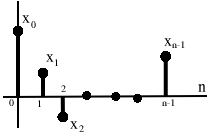

Model for: Discrete time signals on the interval \([0,n−1]\) or periodic (with period \(n\)) discrete time signals. \[\left(\begin{array}{c}

x_{0} \\

x_{1} \\

\dots \\

x_{n-1}

\end{array}\right)\nonumber \]

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)

\( f \in L^2 ([a,b])\) is a finite energy function on \([a,b]\)

Inner Product

\[\langle f, g\rangle=\int_{a}^{b} f(t) \overline{g(t)} \mathrm{d} t \nonumber \]

Model for: continuous time signals on the interval \([a,b]\) or periodic (with period \(T=b−a\)) continuous time signals

\(x \in \ell^{2}(\mathbb{Z})\) is an infinite sequence of numbers that's square-summable

Inner product

\[\langle x, y\rangle=\sum_{i=-\infty}^{\infty} x[i] \overline{y[i]} \nonumber \]

Model for: discrete time, non-periodic signals

\(f \in L^{2}(\mathbb{R})\) is a finite energy function on all of \(\mathbb{R}\).

Inner product

\[\langle f, g\rangle=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(t) \overline{g(t)} \mathrm{d} t \nonumber \]

Model for: continuous time, non-periodic signals

Associated Fourier Analysis

Each of these 4 Hilbert spaces has a type of Fourier analysis associated with it.

- \(L^2([a,b])\) → Fourier series

- \(\ell^{2}([0, n-1])\) → Discrete Fourier Transform

- \(L^{2}(\mathbb{R})\) → Fourier Transform

- \(\ell^{2}(\mathbb{Z})\) → Discrete Time Fourier Transform

But all 4 of these are based on the same principles (Hilbert space).

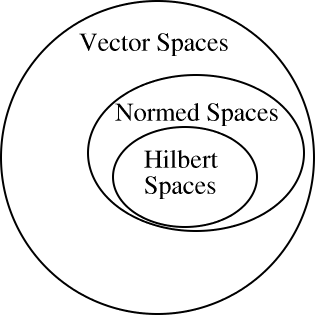

Important Note

Not all normed spaces are Hilbert spaces

For example: \(L^1(\mathbb{R})\), \(\|f\|_{1}=\int|f(t)| d t\). Try as you might, you can't find an inner product that induces this norm, i.e. a \(\langle\cdot, \cdot\rangle\) such that

\[\begin{align}

\langle f, f\rangle &=\left(\int(|f(t)|)^{2} \mathrm{d} t\right)^{2} \nonumber \\

&=\left(\|f\|_{1}\right)^{2}

\end{align} \nonumber \]

In fact, of all the \(L^p(\mathbb{R})\) spaces, \(L^2(\mathbb{R})\) is the only one that is a Hilbert space.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Hilbert spaces are by far the nicest. If you use or study orthonormal basis expansion (Section 15.9) then you will start to see why this is true.