5.2: Water for School Use in La Yuca, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

- Page ID

- 11943

In 2010, Practivistas Chiapas (the summer abroad program) was mandated by the California State University system to move out of Mexico because of the drug war. In search of new locations, I landed in Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. The Dominican Republic shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti. My first night there was filled with what have become sounds of comfort for me: the streams of music, especially bachata (a Dominican bitter-yet-romantic couples dance music), from every colmado (very social corner stores) and the clack of dominoes.

Walking around the city, I met many interesting locals and one angry Spaniard. He told me how Dominicans didn’t care about the environment. I told him that I was going to an event being held by the local 350.org group the next morning. The event was to raise awareness for climate change, especially from the viewpoint of an island country that will be heavily affected by sea-level rise. The event was a great success and DR was the only island country to be satellite photographed for the global 350.org event (Figure 5-3). At the event, I got to know Colectivo Revark, a non-profit founded by the intrepid local architects Wilfredo Mena Veras, Abel Castillo Reynoso, and Joel Mercedes Sanchez. We eventually became close friends and colleagues but first, we built a relationship based on trust, work, and dancing. Colectivo Revark had just held an “Architecture for Earthquake Disaster Relief” competition, called Sismos 2.0. We worked together to judge the submittals. After that successful experience, we built the relationship from afar (I returned to the US), and started working on developing the Practivistas Dominicana Program.

The next year, in 2011, we returned to work with Colectivo Revark and study at Universidad Iberoamericana (UNIBE) under the care of the Director of Architecture, Elmer Gonzalez. Outside of the university, Colectivo Revark was our community liaison and was critical in all the community engagements—yet our community engagement in La Yuca almost did not happen.

La Yuca is one of the most financially poor urban barrios in the center of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. La Yuca contains one school, whose schoolyard also serves as the hub of activities for children. You can touch the walls of houses on both sides of the narrow streets as you make your way through the serpentine labyrinth of the neighborhood. If a moped is coming through, you need to press yourself out of the way. The neighborhood bustles with constant activity and noise, including the comforting endemic rhythms of bachata and dominoes. Overhead, masses of makeshift grid electricity extend into the crevices of every home. These floating balls of electrical spaghetti are worked on by many people of La Yuca as repurposed wires burn out in spectacular light shows and need to be replaced.

The story we first heard from a beautiful ninety-year-old abuela is that La Yuca was originally a temporary home settled by the workers who built much of the surrounding parts of the city, and then the workers didn’t leave. There have been many attempts to push La Yuca and its inhabitants out of the city, but La Yuca has prevailed.

Colectivo Revark and UNIBE helped set up our first community meeting with the junta de vecinos (city council) of La Yuca. During that first community meeting, the reception was low energy and the junta de vecinos seemed mostly uninterested in working together. It was only after the pastor understood what we were proposing and restated it with eloquence, that the engagement happened. He reiterated that we were not there as a charity organization. We were not there with a “solution.” We were not there to drop something off and take pictures. We were there to work and learn together. We were there to seek solutions together. And we were there so that we could all gain knowledge, capacity, and build a better future together.

After that initial meeting, we decided to have a meeting open to the entire community where we could identify our top needs and resources. Some top needs included clean water (some people were spending over 40% of their income on water), more school space (there are more students than can fit in the school), electricity (11% of Santo Domingo re-appropriates their electricity), and jobs (incomes are often just a couple of dollars a day).

The open community meeting was loud and fruitful, especially due to the deep support of the town mayor, Osvaldo de Aza Carpio. We brainstormed dozens of available resources and top needs. Then we prioritized the top needs into just a few and broke off into small groups to brainstorm solutions to those top needs... but suddenly, the previously loud meeting became quiet. With the help of our community partner Colectivo Revark, I realized that an assumption I had made was about to weaken the community meeting. When working in a rural environment, I keep in mind that many of the participants may not be comfortable writing in front of others. I missed that that might be true as well in the urban environment of Santo Domingo. Quickly we changed the break-off groups so that one person, someone we knew would be comfortable writing in front of people, was writing in each group. The noise and cacophony of creation came back up and the results led to years of engagement.

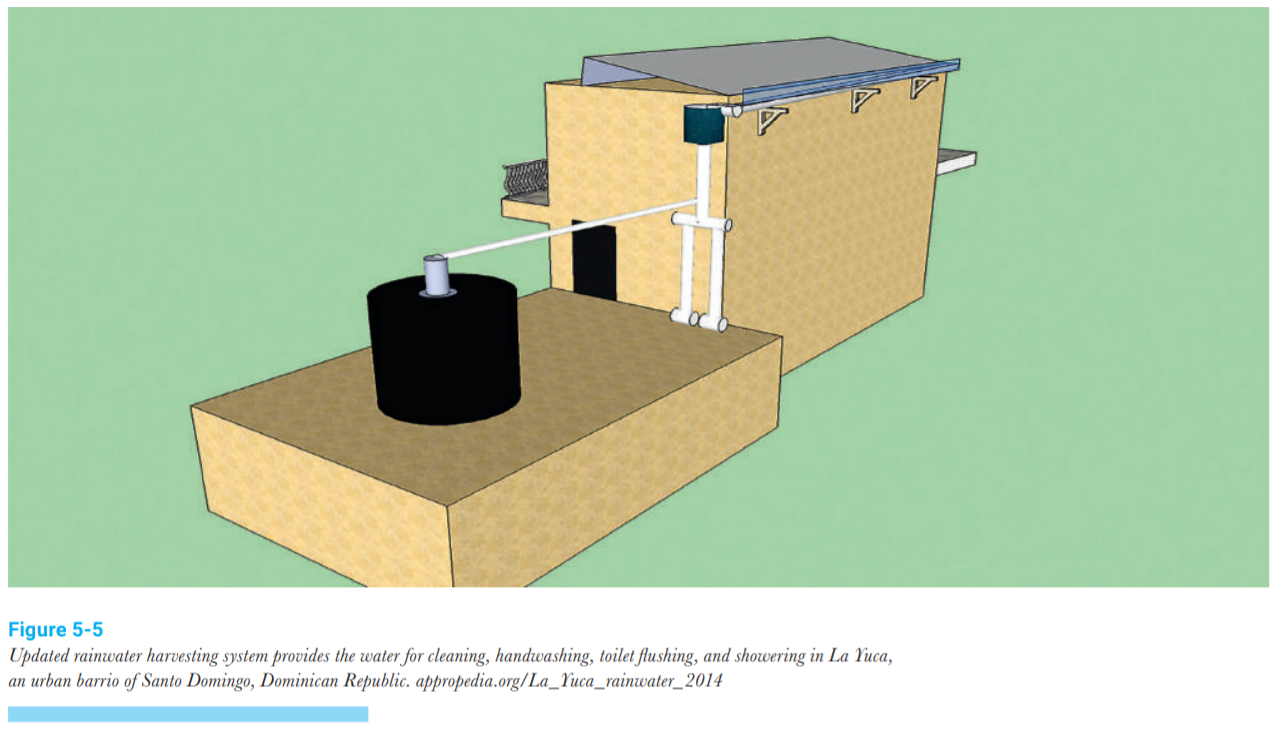

Together we decided to create a wind and solar renewable energy system, a schoolroom from plastic bottles (a style called ecoladrillo), and a rainwater harvesting system on top of the new schoolroom we were building together. The school was currently ordering two trucks worth of water per month, which was expensive and was only enough water to clean the school and to flush the toilet manually at night. The school had no water for hand washing in the toilet nor anywhere else (a major health indicator).

Together we built a 2000-liter rainwater harvesting system that also included additional storage in an existing cistern; however, the rainwater project at the grade school in La Yuca took a few years of iteration to get right. The first year, it caught water . . . but the water wasn’t really trusted by the users because the slow-sand filter looked too “rural” to the users. Therefore, we replaced the slow-sand filter with more urban-looking canister filters.

Another problem was that the original gutter system, which consisted of PVC sliced open and pressed over the edge of the corrugated roof, was too flat and was getting clogged, causing it to sag and leak. In 2014, we replaced the PVC with a new, more conventional K-type gutter, which fixed the sagging and leaking problem (Figure 5-4). We also added a fabricated splash guard to protect the very close neighbors from splashing during heavy rains.