2.2: Point Forces as Vectors

- Page ID

- 50573

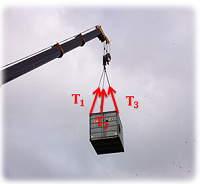

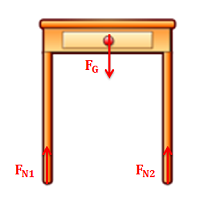

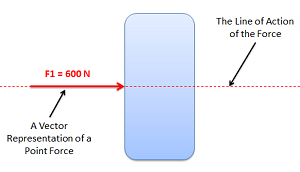

A point force is any force where the point of application is considered to be a single point. In reality, most forces are technically surface forces, where the force is applied over an area, but when the area is small enough (in comparison to the bodies being analyzed) it can often be approximated as a point force. Because point forces can be represented as a single vector (rather than a field of vectors for distributed forces), they are much easier to work with in engineering analysis. For this reason, point forces are used in place of distributed forces in engineering analysis whenever possible. Below are some examples of where it is appropriate to use point forces.

.png?revision=1)

In addition to the magnitude, direction, and point of application of the point force, another important term to understand is the line of action of the force. The line of action of a force is the line along which the force acts. Given the direction and point of application, one can find the line of action, but this term will be important in discussing concurrent forces and in the principle of transmissibility.

Force Vector Representation:

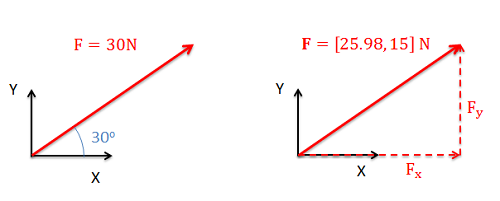

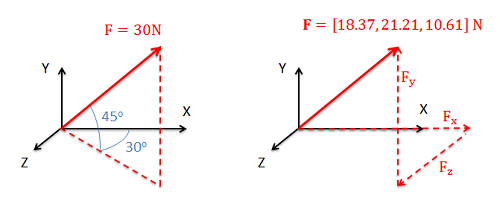

When vectors are drawn to form free body diagrams, the magnitude and direction are usually given in one of two formats:

- Overall magnitude and angle(s) to indicate direction (often called magnitude and direction form).

- Magnitudes in each of the coordinate directions (often called component form).

In either format we will need two values to fully define a force vector in a 2D system (either a magnitude and a single angle or a magnitude in each of the two coordinate axes), and three values to fully define a force vector in a 3D system (either a magnitude and two angles or a magnitude in each of the three coordinate axes). Below are some examples of force vectors in both representations.

Changing Force Vector Forms:

Because the two different forms of the vector are equivalent, we can switch between representations without changing the problem. Often in engineering problems, it will initially be easier to write the force in magnitude and angle form, but later, analysis will be easier if forces are written in component form. To switch from magnitude and direction form to component form you will use right triangles and trigonometry to determine the component of the overall magnitude in each direction. This is a simple vector decomposition, and more information on this process can be seen on the vector decomposition page. To switch back from component form into magnitude and direction form you simply use the reverse of this initial process.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The tension force on the box below is given in magnitude and direction form. Redraw the diagram with the tension force given in component form.

.png?revision=1)

- Solution

-

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Worked solution to example problem \(\PageIndex{1}\), provided by Dr. Jacob Moore. YouTube source: https://youtu.be/ZERURXWnlDg.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

The force acting on the cantilever beam shown below is given in component form. Redraw the diagram with the force given in magnitude and direction form.

![A cantilever beam attached to a wall, with a force with the components [-300, -250] N being applied to the free end.](https://eng.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/41503/P2_(1).png?revision=1)

- Solution

-

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Worked solution to example problem \(\PageIndex{2}\), provided by Dr. Jacob Moore. YouTube source: https://youtu.be/M3UjDfZzRHY.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

The force shown below is given in magnitude and direction form. Redraw the diagram with the force vector given in component form.

.png?revision=1)

- Solution

-

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Worked solution to example problem \(\PageIndex{3}\), delivered by Dr. Jacob Moore. YouTube source: https://youtu.be/DroNv0TxnyA.