1.2: Types and Number Representation

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 82834

Types and Number Representation

C Standards

Although a slight divergence, it is important to understand a bit of history about the C language.

C is the common languge of the systems programming world. Every operating system and its associated system libraries in common use is written in C, and every system provides a C compiler. To stop the language diverging across each of these systems where each would be sure to make numerous incompatible changes, a strict standard has been written for the language.

Officially this standard is known as ISO/IEC 9899:1999(E),

but is more commonly referred to by its shortened name

C99. The standard is maintained by the

International Standards Organisation (ISO) and the full standard

is available for purchase online. Older standards versions such

as C89 (the predecessor to C99 released in 1989) and ANSI C are

no longer in common usage and are encompassed within the latest

standard. The standard documentation is very technical, and

details most every part of the language. For example it

explains the syntax (in Backus Naur form), standard

#define values and how

operations should behave.

It is also important to note what the C standards does not define. Most importantly the standard needs to be appropriate for every architecture, both present and future. Consequently it takes care not to define areas that are architecture dependent. The "glue" between the C standard and the underlying architecture is the Application Binary Interface (or ABI) which we discuss below. In several places the standard will mention that a particular operation or construct has an unspecified or implementation dependent result. Obviously the programmer can not depend on these outcomes if they are to write portable code.

GNU C

The GNU C Compiler, more commonly referred to as gcc, almost completely implements the C99 standard. However it also implements a range of extensions to the standard which programmers will often use to gain extra functionality, at the expense of portability to another compiler. These extensions are usually related to very low level code and are much more common in the system programming field; the most common extension being used in this area being inline assembly code. Programmers should read the gcc documentation and understand when they may be using features that diverge from the standard.

gcc can be directed to adhere

strictly to the standard (the

-std=c99 flag for example)

and warn or create an error when certain things are done that

are not in the standard. This is obviously appropriate if you

need to ensure that you can move your code easily to another

compiler.

Types

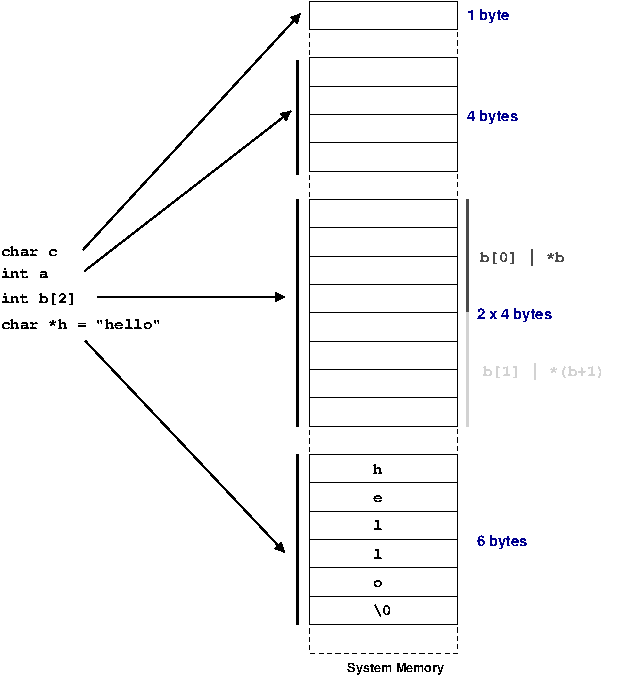

As programmers, we are familiar with using variables to represent an area of memory to hold a value. In a typed language, such as C, every variable must be declared with a type. The type tells the compiler about what we expect to store in a variable; the compiler can then both allocate sufficient space for this usage and check that the programmer does not violate the rules of the type. In the example below, we see an example of the space allocated for some common types of variables.

The C99 standard purposely only mentions the smallest possible size of each of the types defined for C. This is because across different processor architectures and operating systems the best size for types can be wildly different.

To be completely safe programmers need to never assume the size of any of their variables, however a functioning system obviously needs agreements on what sizes types are going to be used in the system. Each architecture and operating system conforms to an Application Binary Interface or ABI. The ABI for a system fills in the details between the C standard and the requirements of the underlying hardware and operating system. An ABI is written for a specific processor and operating system combination.

| Type | C99 minimum size (bits) | Common size (32 bit architecture) |

|---|---|---|

char

| 8 | 8 |

short

| 16 | 16 |

int

| 16 | 32 |

long

| 32 | 32 |

long long

| 64 | 64 |

| Pointers | Implementation dependent | 32 |

Above we can see the only divergence from the standard is

that int is commonly a 32 bit

quantity, which is twice the strict minimum 16 bit size that the

C99 requires.

Pointers are really just an address (i.e. their value is an address and thus "points" somewhere else in memory) therefore a pointer needs to be sufficient in size to be able to address any memory in the system.

64 bit

One area that causes confusion is the introduction of 64 bit computing. This means that the processor can handle addresses 64 bits in length (specifically the registers are 64 bits wide; a topic we discuss in Chapter 3, Computer Architecture).

This firstly means that all pointers are required to be a 64 bits wide so they can represent any possible address in the system. However, system implementers must then make decisions about the size of the other types. Two common models are widely used, as shown below.

| Type | C99 minimum size (bits) | Common size (LP64) | Common size (Windows) |

|---|---|---|---|

char

| 8 | 8 | 8 |

short

| 16 | 16 | 16 |

int

| 16 | 32 | 32 |

long

| 32 | 64 | 32 |

long long

| 64 | 64 | 64 |

| Pointers | Implementation dependent | 64 | 64 |

You can see that in the LP64 (long-pointer 64) model

long values are defined to be

64 bits wide. This is different to the 32 bit model we showed

previously. The LP64 model is widely used on UNIX

systems.

In the other model,

long remains a 32 bit value.

This maintains maximum compatibility with 32 code. This model

is in use with 64 bit Windows.

There are good reasons why the size of

int was not increased to 64

bits in either model. Consider that if the size of

int is increased to 64 bits

you leave programmers no way to obtain a 32 bit variable. The

only possibly is redefining

shorts to be a larger 32 bit

type.

A 64 bit variable is so large that it is not generally required to represent many variables. For example, loops very rarely repeat more times than would fit in a 32 bit variable (4294967296 times!). Images usually are usually represented with 8 bits for each of a red, green and blue value and an extra 8 bits for extra (alpha channel) information; a total of 32 bits. Consequently for many cases, using a 64 bit variable will be wasting at least the top 32 bits (if not more). Not only this, but the size of an integer array has now doubled too. This means programs take up more system memory (and thus more cache; discussed in detail in Chapter 3, Computer Architecture) for no real improvement. For the same reason Windows elected to keep their long values as 32 bits; since much of the Windows API was originally written to use long variables on a 32 bit system and hence does not require the extra bits this saves considerable wasted space in the system without having to re-write all the API.

If we consider the proposed alternative where

short was redefined to be a

32 bit variable; programmers working on a 64 bit system could

use it for variables they know are bounded to smaller values.

However, when moving back to a 32 bit system their same

short variable would now be

only 16 bits long, a value which is much more realistically

overflowed (65536).

By making a programmer request larger variables when they know they will be needed strikes a balance with respect to portability concerns and wasting space in binaries.

Type qualifiers

The C standard also talks about some qualifiers for

variable types. For example

const means that a variable

will never be modified from its original value and

volatile suggests to the

compiler that this value might change outside program

execution flow so the compiler must be careful not to re-order

access to it in any way.

signed and

unsigned are probably the two

most important qualifiers; and they say if a variable can take

on a negative value or not. We examine this in more detail

below.

Qualifiers are all intended to pass extra information

about how the variable will be used to the compiler. This

means two things; the compiler can check if you are violating

your own rules (e.g. writing to a

const value) and it can make

optimisations based upon the extra knowledge (examined in

later chapters).

Standard Types

C99 realises that all these rules, sizes and portability

concerns can become very confusing very quickly. To help, it

provides a series of special types which can specify the exact

properties of a variable. These are defined in

<stdint.h> and have the

form qtypes_t where

q is a qualifier,

type is the base type,

s is the width in bits and

_t is an extension so you

know you are using the C99 defined types.

So for example uint8_t

is an unsigned integer exactly 8 bits wide. Many other types

are defined; the complete list is detailed in C99 17.8 or

(more cryptically) in the header file. [3]

It is up to the system implementing the C99 standard to provide these types for you by mapping them to appropriate sized types on the target system; on Linux these headers are provided by the system libraries.

Types in action

Below in Example 2.3, “Example of warnings when types are not matched” we see an

example of how types place restrictions on what operations are

valid for a variable, and how the compiler can use this

information to warn when variables are used in an incorrect

fashion. In this code, we firstly assign an integer value

into a char variable. Since

the char variable is smaller,

we loose the correct value of the integer. Further down, we

attempt to assign a pointer to a

char to memory we designated

as an integer. This

operation can be done; but it is not safe. The first example

is run on a 32-bit Pentium machine, and the correct value is

returned. However, as shown in the second example, on a

64-bit Itanium machine a pointer is 64 bits (8 bytes) long,

but an integer is only 4 bytes long. Clearly, 8 bytes can not

fit into 4! We can attempt to "fool" the compiler by

casting the value before assigning it;

note that in this case we have shot ourselves in the foot by

doing this cast and ignoring the compiler warning since the

smaller variable can not hold all the information from the

pointer and we end up with an invalid address.

1 /* * types.c */ 5 #include <stdio.h> #include <stdint.h> int main(void) { 10 char a; char *p = "hello"; int i; 15 // moving a larger variable into a smaller one i = 0x12341234; a = i; i = a; printf("i is %d\n", i); 20 // moving a pointer into an integer printf("p is %p\n", p); i = p; // "fooling" with casts 25 i = (int)p; p = (char*)i; printf("p is %p\n", p); return 0; 30 }

1 $ uname -m i686 $ gcc -Wall -o types types.c 5 types.c: In function 'main': types.c:19: warning: assignment makes integer from pointer without a cast $ ./types i is 52 10 p is 0x80484e8 p is 0x80484e8 $ uname -m ia64 15 $ gcc -Wall -o types types.c types.c: In function 'main': types.c:19: warning: assignment makes integer from pointer without a cast types.c:21: warning: cast from pointer to integer of different size 20 types.c:22: warning: cast to pointer from integer of different size $ ./types i is 52 p is 0x40000000000009e0 25 p is 0x9e0

Number Representation

Negative Values

With our modern base 10 numeral system we indicate a

negative number by placing a minus

(-) sign in front of it.

When using binary we need to use a different system to

indicate negative numbers.

There is only one scheme in common use on modern hardware, but C99 defines three acceptable methods for negative value representation.

Sign Bit

The most straight forward method is to simply say that one bit of the number indicates either a negative or positive value depending on it being set or not.

This is analogous to mathematical approach of having a

+ and

-. This is fairly logical,

and some of the original computers did represent negative

numbers in this way. But using binary numbers opens up some

other possibilities which make the life of hardware designers

easier.

However, notice that the value

0 now has two equivalent

values; one with the sign bit set and one without.

Sometimes these values are referred to as

+0 and

-0 respectively.

One's Complement

One's complement simply applies the

not operation to the positive number to

represent the negative number. So, for example the value

-90 (-0x5A) is represented by ~01011010 =

10100101[4]

With this scheme the biggest advantage is that to add a negative number to a positive number no special logic is required, except that any additional carry left over must be added back to the final value. Consider

| Decimal | Binary | Op |

|---|---|---|

| -90 | 10100101 | + |

| 100 | 01100100 | |

| --- | -------- | |

| 10 | 100001001 | 9 |

| 00001010 | 10 |

If you add the bits one by one, you find you end up with a carry bit at the end (highlighted above). By adding this back to the original we end up with the correct value, 10

Again we still have the problem with two zeros being represented. Again no modern computer uses one's complement, mostly because there is a better scheme.

Two's Complement

Two's complement is just like one's complement, except

the negative representation has one

added to it and we discard any left over carry bit. So to

continue with the example from before,

-90 would be

~01011010+1=10100101+1 =

10100110.

This means there is a slightly odd symmetry in the

numbers that can be represented; for example with an 8 bit

integer we have

2^8 =

256 possible values; with our sign bit

representation we could represent -127 thru 127 but with

two's complement we can represent -127 thru 128. This is

because we have removed the problem of having two zeros;

consider that "negative zero" is (~00000000

+1)=(11111111+1)=00000000 (note

discarded carry bit).

| Decimal | Binary | Op |

|---|---|---|

| -90 | 10100110 | + |

| 100 | 01100100 | |

| --- | -------- | |

| 10 | 00001010 |

You can see that by implementing two's complement hardware designers need only provide logic for addition circuits; subtraction can be done by two's complement negating the value to be subtracted and then adding the new value.

Similarly you could implement multiplication with repeated addition and division with repeated subtraction. Consequently two's complement can reduce all simple mathematical operations down to addition!

All modern computers use two's complement representation.

Sign-extension

Because of two's complement format, when increasing the size of signed value, it is important that the additional bits be sign-extended; that is, copied from the top-bit of the existing value.

For example, the value of an 32-bit

int

-10 would be represented

in two's complement binary as

11111111111111111111111111110110.

If one were to cast this to a 64-bit long

long int, we would need to ensure that

the additional 32-bits were set to

1 to maintain the same

sign as the original.

Thanks to two's complement, it is sufficient to take the top bit of the exiting value and replace all the added bits with this value. This processes is referred to as sign-extension and is usually handled by the compiler in situations as defined by the language standard, with the processor generally providing special instructions to take a value and sign-extended it to some larger value.

Floating Point

So far we have only discussed integer or whole numbers; the class of numbers that can represent decimal values is called floating point.

To create a decimal number, we require some way to represent the concept of the decimal place in binary. The most common scheme for this is known as the IEEE-754 floating point standard because the standard is published by the Institute of Electric and Electronics Engineers. The scheme is conceptually quite simple and is somewhat analogous to "scientific notation".

In scientific notation the value

123.45 might commonly be

represented as

1.2345x102.

We call 1.2345 the

mantissa or

significand,

10 is the

radix and

2 is the

exponent.

In the IEEE floating point model, we break up the

available bits to represent the sign, mantissa and exponent of

a decimal number. A decimal number is represented by

sign × significand ×

2^exponent.

The sign bit equates to either

1 or

-1. Since we are working in

binary, we always have the implied radix of

2.

There are differing widths for a floating point value -- we examine below at only a 32 bit value. More bits allows greater precision.

| Sign | Exponent | Significand/Mantissa |

|---|---|---|

| S | EEEEEEEE | MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM |

The other important factor is bias

of the exponent. The exponent needs to be able to represent

both positive and negative values, thus an implied value of

127 is subtracted from the

exponent. For example, an exponent of

0 has an exponent field of

127,

128 would represent

1 and

126 would represent

-1.

Each bit of the significand adds a little more precision

to the values we can represent. Consider the scientific

notation representation of the value

198765. We could write this

as

1.98765x106,

which corresponds to a representation below

| 100 | . | 10-1 | 10-2 | 10-3 | 10-4 | 10-5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | . | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

Each additional digit allows a greater range of decimal

values we can represent. In base 10, each digit after the

decimal place increases the precision of our number by 10

times. For example, we can represent

0.0 through

0.9 (10 values) with one

digit of decimal place, 0.00

through 0.99 (100 values)

with two digits, and so on. In binary, rather than each

additional digit giving us 10 times the precision, we only get

two times the precision, as illustrated in the table below.

This means that our binary representation does not always map

in a straight-forward manner to a decimal

representation.

| 20 | . | 2-1 | 2-2 | 2-3 | 2-4 | 2-5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | . | 1/2 | 1/4 | 1/8 | 1/16 | 1/32 |

| 1 | . | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.0625 | 0.03125 |

With only one bit of precision, our fractional precision

is not very big; we can only say that the fraction is either

0 or

0.5. If we add another bit

of precision, we can now say that the decimal value is one of

either 0,0.25,0.5,0.75. With

another bit of precision we can now represent the values

0,0.125,0.25,0.375,0.5,0.625,0.75,0.875.

Increasing the number of bits therefore allows us greater and greater precision. However, since the range of possible numbers is infinite we will never have enough bits to represent any possible value.

For example, if we only have two bits of precision and

need to represent the value

0.3 we can only say that it

is closest to 0.25; obviously

this is insufficient for most any application. With 22 bits

of significand we have a much finer resolution, but it is

still not enough for most applications. A

double value increases the

number of significand bits to 52 (it also increases the range

of exponent values too). Some hardware has an 84-bit float,

with a full 64 bits of significand. 64 bits allows a

tremendous precision and should be suitable for all but the

most demanding of applications (XXX is this sufficient to

represent a length to less than the size of an atom?)

1 $ cat float.c

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

5 {

float a = 0.45;

float b = 8.0;

double ad = 0.45;

10 double bd = 8.0;

printf("float+float, 6dp : %f\n", a+b);

printf("double+double, 6dp : %f\n", ad+bd);

printf("float+float, 20dp : %10.20f\n", a+b);

15 printf("dobule+double, 20dp : %10.20f\n", ad+bd);

return 0;

}

20 $ gcc -o float float.c

$ ./float

float+float, 6dp : 8.450000

double+double, 6dp : 8.450000

25 float+float, 20dp : 8.44999998807907104492

dobule+double, 20dp : 8.44999999999999928946

$ python

Python 2.4.4 (#2, Oct 20 2006, 00:23:25)

30 [GCC 4.1.2 20061015 (prerelease) (Debian 4.1.1-16.1)] on linux2

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> 8.0 + 0.45

8.4499999999999993

35 A practical example is illustrated above. Notice that

for the default 6 decimal places of precision given by

printf both answers are the

same, since they are rounded up correctly. However, when

asked to give the results to a larger precision, in this case

20 decimal places, we can see the results start to diverge.

The code using doubles has a

more accurate result, but it is still not

exactly correct. We can also see that

programmers not explicitly dealing with

float values still have

problems with precision of variables!

Normalised Values

In scientific notation, we can represent a value in

many different ways. For example,

10023x10^0 =

1002.3x101 =

100.23x102. We

thus define the normalised version as

the one where 1/radix <= significand <

1. In binary this ensures that the

leftmost bit of the significand is always

one. Knowing this, we can gain an extra bit of

precision by having the standard say that the leftmost bit

being one is implied.

| 20 | . | 2-1 | 2-2 | 2-3 | 2-4 | 2-5 | Exponent | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | . | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2^0 | (0.25+0.125) × 1 = 0.375 |

| 0 | . | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2^-1 | (0.5+0.25)×.5=0.375 |

| 1 | . | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2^-2 | (1+0.5)×0.25=0.375 |

As you can see above, we can make the value normalised by moving the bits upwards as long as we compensate by increasing the exponent.

Normalisation Tricks

A common problem programmers face is finding the

first set bit in a bitfield. Consider the bitfield

0100; from the right the

first set bit would be bit

2 (starting from zero, as

is conventional).

The standard way to find this value is to shift

right, check if the uppermost bit is a

1 and either terminate or

repeat. This is a slow process; if the bitfield is 64

bits long and only the very last bit is set, you must go

through all the preceding 63 bits!

However, if this bitfield value were the signficand of a floating point number and we were to normalise it, the value of the exponent would tell us how many times it was shifted. The process of normalising a number is generally built into the floating point hardware unit on the processor, so operates very fast; usually much faster than the repeated shift and check operations.

The example program below illustrates two methods of

finding the first set bit on an Itanium processor. The

Itanium, like most server processors, has support for an

80-bit extended floating point type,

with a 64-bit significand. This means a

unsigned long neatly fits

into the significand of a long

double. When the value is loaded it is

normalised, and and thus by reading the exponent value

(minus the 16 bit bias) we can see how far it was

shifted.

1 #include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

5 // in binary = 1000 0000 0000 0000

// bit num 5432 1098 7654 3210

int i = 0x8000;

int count = 0;

while ( !(i & 0x1) ) {

10 count ++;

i = i >> 1;

}

printf("First non-zero (slow) is %d\n", count);

15 // this value is normalised when it is loaded

long double d = 0x8000UL;

long exp;

// Itanium "get floating point exponent" instruction

20 asm ("getf.exp %0=%1" : "=r"(exp) : "f"(d));

// note exponent include bias

printf("The first non-zero (fast) is %d\n", exp - 65535);

25 }

Bringing it together

In the example code below we extract the components of

a floating point number and print out the value it

represents. This will only work for a 32 bit floating point

value in the IEEE format; however this is common for most

architectures with the

float type.

1 #include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> #include <stdlib.h> 5 /* return 2^n */ int two_to_pos(int n) { if (n == 0) return 1; 10 return 2 * two_to_pos(n - 1); } double two_to_neg(int n) { 15 if (n == 0) return 1; return 1.0 / (two_to_pos(abs(n))); } 20 double two_to(int n) { if (n >= 0) return two_to_pos(n); if (n < 0) 25 return two_to_neg(n); return 0; } /* Go through some memory "m" which is the 24 bit significand of a 30 floating point number. We work "backwards" from the bits furthest on the right, for no particular reason. */ double calc_float(int m, int bit) { /* 23 bits; this terminates recursion */ 35 if (bit > 23) return 0; /* if the bit is set, it represents the value 1/2^bit */ if ((m >> bit) & 1) 40 return 1.0L/two_to(23 - bit) + calc_float(m, bit + 1); /* otherwise go to the next bit */ return calc_float(m, bit + 1); } 45 int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { float f; int m,i,sign,exponent,significand; 50 if (argc != 2) { printf("usage: float 123.456\n"); exit(1); 55 } if (sscanf(argv[1], "%f", &f) != 1) { printf("invalid input\n"); 60 exit(1); } /* We need to "fool" the compiler, as if we start to use casts (e.g. (int)f) it will actually do a conversion for us. We 65 want access to the raw bits, so we just copy it into a same sized variable. */ memcpy(&m, &f, 4); /* The sign bit is the first bit */ 70 sign = (m >> 31) & 0x1; /* Exponent is 8 bits following the sign bit */ exponent = ((m >> 23) & 0xFF) - 127; 75 /* Significand fills out the float, the first bit is implied to be 1, hence the 24 bit OR value below. */ significand = (m & 0x7FFFFF) | 0x800000; /* print out a power representation */ 80 printf("%f = %d * (", f, sign ? -1 : 1); for(i = 23 ; i >= 0 ; i--) { if ((significand >> i) & 1) printf("%s1/2^%d", (i == 23) ? "" : " + ", 85 23-i); } printf(") * 2^%d\n", exponent); /* print out a fractional representation */ 90 printf("%f = %d * (", f, sign ? -1 : 1); for(i = 23 ; i >= 0 ; i--) { if ((significand >> i) & 1) printf("%s1/%d", (i == 23) ? "" : " + ", 95 (int)two_to(23-i)); } printf(") * 2^%d\n", exponent); /* convert this into decimal and print it out */ 100 printf("%f = %d * %.12g * %f\n", f, (sign ? -1 : 1), calc_float(significand, 0), two_to(exponent)); 105 /* do the math this time */ printf("%f = %.12g\n", f, (sign ? -1 : 1) * 110 calc_float(significand, 0) * two_to(exponent) ); return 0; 115 }

Sample output of the value

8.45, which we previously

examined, is shown below.

8.45$ ./float 8.45 8.450000 = 1 * (1/2^0 + 1/2^5 + 1/2^6 + 1/2^7 + 1/2^10 + 1/2^11 + 1/2^14 + 1/2^15 + 1/2^18 + 1/2^19 + 1/2^22 + 1/2^23) * 2^3 8.450000 = 1 * (1/1 + 1/32 + 1/64 + 1/128 + 1/1024 + 1/2048 + 1/16384 + 1/32768 + 1/262144 + 1/524288 + 1/4194304 + 1/8388608) * 2^3 8.450000 = 1 * 1.05624997616 * 8.000000 8.450000 = 8.44999980927

From this example, we get some idea of how the inaccuracies creep into our floating point numbers.

[3] Note

that C99 also has portability helpers for

printf. The

PRI macros in

<inttypes.h> can be

used as specifiers for types of specified sizes. Again see

the standard or pull apart the headers for full

information.

[4] The

~ operator is the C

language operator to apply

NOT to the value. It is

also occasionally called the one's complement operator, for

obvious reasons now!