6.1.3: Types of Listening

- Page ID

- 75169

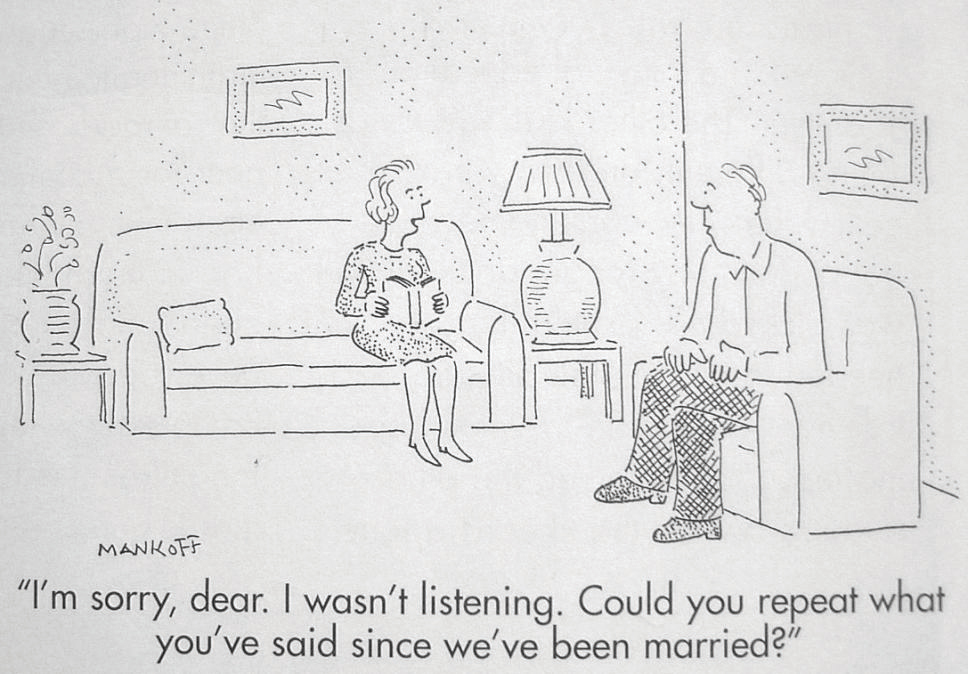

I’d invited my wife to accompany me to a professional conference in Portland. Since I was going to be making a presentation there, my colleague and co-presenter Sally was with us for the trip down and back.

Driving along the Interstate, Sally and I talked shop. What about our supervisor? Yak yak yak. What about our faculty union? Yak yak yak. And our plans for next year? Yak yak yak.

After 20 minutes of chatter with Sally, I realized that what we were discussing might not mean much to my wife. Being the considerate guy that I am, I paused and looked over at her.

“Sorry we’ve been talking so much about work. Thanks for listening.”

“I’m not listening,” she replied.

Preferences, Purposes, and Types of Listening

People speak for various reasons and with various goals in mind. Likewise, the ways we listen vary according to our preferences and purposes. Several theorists have identified types of listening which can help us understand our own behavior and that of others.

Galanes and Adams, Galanes, G., & Adams, K. (2013). Effective group discussion: Theory and practice. New York: McGraw-Hill. wrote that people fall into four possible orientation categories as they listen to one another in groups. People-oriented listeners, also known as “relational listeners,” direct themselves toward detecting and preserving positive emotional features of a relationship. For instance, best friends are probably people who practice nonjudgmental listening in an effort to understand and support each other. In a group, people-oriented listeners may share their feelings openly and strive to defuse anger or frustration on the part of other members.

Action-oriented listeners, by comparison, prefer to focus on tasks that they and their fellow communicators have set for themselves. (Think back to chapter 1, where we differentiated between the “task” and “relationship” sides of group interaction). Action-oriented listeners will generally retain and share details and information which they believe will keep a group moving.

Content-oriented listeners are those who care particularly about the specifics of a group’s discussions. They tend to seek, provide, and analyze information that has been gathered through research. What they primarily choose to hear and to share with others, thus, is material that they consider to be factual.

Time-oriented listeners concern themselves above all with how a group’s activities fit into a calendar or schedule. They may listen and watch especially for signs that other group members want to accelerate the pace of the group’s activities. Their preference is usually for short, concise messages rather than extended ones.

In the real world, few people fit neatly and completely into a single category within Galanes and Adams’s typology of listeners. Instead, each of us embodies a mixture of the four preferences depending on the topic a group is dealing with, the developmental stage of the group, and other factors.

Like Galanes and Adams, Waldeck, Kearney, and PlaxWaldeck, J. H., Kearney, P., & Plax, T. (2013). Business & professional communication in a digital age. Boston: Wadsworth. proposed four purposes which they believe people have in mind as they listen to others. First, we may want to acquire information. Students listening to class lectures are pursuing this purpose. Second, we may listen in order to screen and evaluate what we hear. For instance, we may have the radio on continuously but listen especially for and to stories and comments which are relevant to our work or study. Third, we may listen recreationally, to relax and enjoy ourselves. Perhaps we listen to music or watch and listen to video images on a mobile device, or we might attend a concert of music we enjoy. Finally, just as Galanes and Adams indicated, we may listen because it helps other people or ourselves from the standpoint of our relationships. When we listen attentively to friends, classmates, or work colleagues, we demonstrate our interest in them and thereby develop positive feelings in them about us.

Beebe and Masterson, Beebe, S.A., & Masterson, J.T. (2006). Communicating in small groups; Principles and practices (8th ed.). Boston: Pearson. cited Allan Glatthorn and Herbert Adams, Glatthorn, A.A., & Adams, H.R. (1984). Listening your way to management success. (Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman). as identifying the following three types of listening:

Type one: hearing. This is the simple physical act of having sound waves enter our ears and be transmitted into neural impulses sent to our brain. In 1965, Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel sang in “The Sound of Silence” about “people hearing but not listening,” and this is really what Glatthorn and Adams were referring to.

Type two: analyzing. Beyond simply receiving sound waves, listeners may employ critical judgment to ascertain the purpose behind a speaker’s message(s). In so doing, they may consider not only the content of the message, but also its stated and unstated intent, its context, and what kind of persuasive strategy the speaker may be using it as part of.

Kelly, Kelly, M.S. (2006). Communication @ work: Ethical, effective, and expressive communication in the workplace. Boston: Pearson. offered a helpful elaboration on this type of listening. She suggested that “analyzing” may also involve discriminating—that is, distinguishing—between information and propaganda, research and personal experience, official business and small talk, and simple information and material which requires a listener to take action.

Type three: empathizing. Empathizing requires that a listener not only discern a speaker’s intention, but also withhold judgment about that person and see things from his or her perspective. Once this is accomplished, it may be possible to respond to the speaker with acceptance.

The Listening Process

Even though listening is a natural human process, and one in which we spend most of our communication time, it may not occur to us how complex the activity really is. Many authorities have proposed models that comprise what they consider to be steps in the process. We’ll consider one such model.

Engleberg & Wynn, Engleberg, I.N., & Wynn, D. R. (2013). Working in groups (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson. described the HURIER model, an acronym developed by Judi Brownell. Brownell, J. (2010). Listening: Attitudes, principles, and skills (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson Allyn & Bacon. That model proposed that, in listening, people first hear; then understand; next interpret (including the emotional grounds/status of the speaker); evaluate (including whether the message is meant to persuade, and if so whether it should do so); remember; and finally respond. Among the strengths of this model for application to group settings are that its steps take a group’s goals into account and that it recognizes both the task and relationship elements of communication.

Foundations for Good Listening

Each of us can probably think of a few people whom we consider to be outstanding listeners. What makes them that way, and what attitudes and behaviors do they display in their listening that we most appreciate? Let’s consider some answers that various theorists have offered concerning the strengths of good listeners.

First, the famous educator and philosopher John Dewey, Dewey, J. (1944). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan. exhorted people to show what he called “intellectual hospitality.” By this, he meant “an active disposition to welcome points of view hitherto alien.” If a person is willing to entertain perspectives outside his or her previous experience, listening can proceed on favorable ground.

Objectivity represents a related initial ingredient in good listening. As Rohlander, Rohlander, D.G. (2000, February). The well-rounded IE. IIE Solutions, 32 (2), 22. wrote, people should be prepared to weigh facts and emotional elements in their listening “on imaginary balanced scales.”

Stewart and Thomas, Stewart, J., & Thomas, M. (1990). Dialogic listening: Sculpting mutual meanings. In J. Stewart (Ed.), Bridges not walls (5th ed.) (pp. 192–210). New York: McGraw-Hill. coined the term “dialogic listening” to identify what they considered to be ideal listening behavior. They characterized dialogic listeners in these ways:

Whatever models they propose, and whatever vocabulary they use, all the authorities who write about listening share the belief that listening needs to be active rather than passive. We’ll provide specific steps later in this chapter for how to engage in active, positive listening.

Negative Kinds of Listening

Now for some unfortunate news. There is a rich array of ways to be a bad listener.

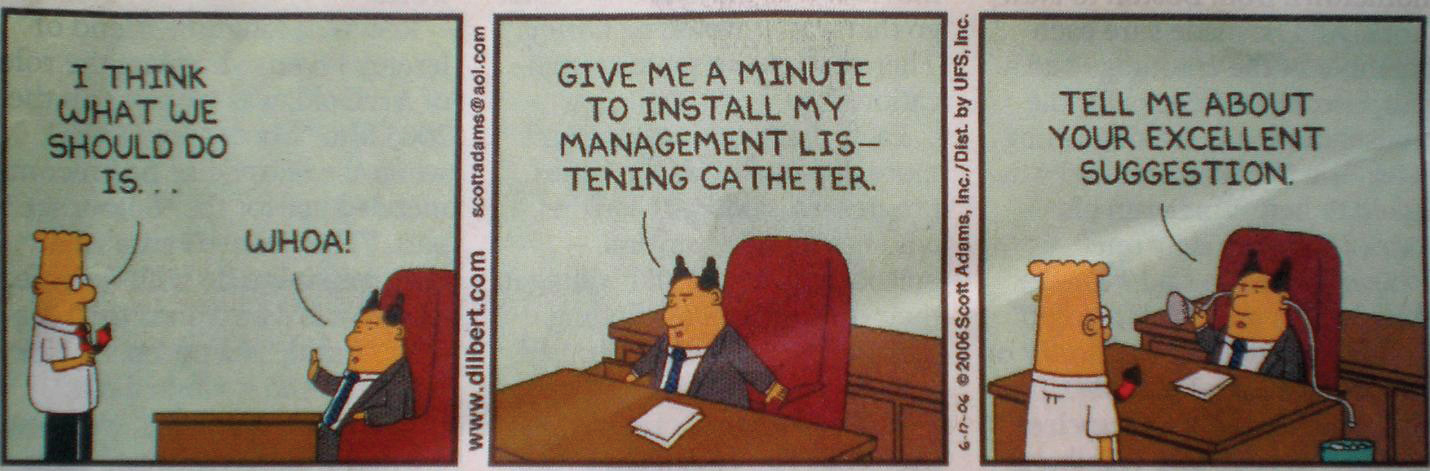

Adler and Towne, Adler, R.B., & Towne, N. (2002). Looking out/looking in (10th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College Publishers. named and described several of these ways. The first is pseudo-listening. You’ve seen this many times in your own life, and probably you’ve even done it. It’s the act of seeming to be listening while your mind is actually somewhere else. When you’re pseudo-listening, you may nod your head and emit periodic sounds of approval, just as you would if you were really paying attention, but those actions are for show.

Then there’s “stage-hogging,” also known as “disruptive listening.” This is an active behavior—but the action isn’t good, since the listener attends only minimally to what the other person is saying and butts in persistently and repeatedly to insert views or express needs of his or her own.

The first panel of a “Far Side” cartoon by Gary Larson shows a man scolding his dog. He starts out by saying, “Okay, Ginger” and then goes on at length. Once or twice more in the harangue the man says Ginger’s name. In the second panel, the “speech balloon” of the master is altered to show what the dog hears: “Blah blah Ginger. Blah blah blah blah blah blah blah GINGER blah blah blah blah…” In this case, the fact that Ginger is a dog means that she can only detect the sound of her own name in her master’s speech. Selective listening among human beings, on the other hand, consists of listening only to the parts of someone else’s communication that are personally important to us—even though we could certainly understand and respond to the rest of it if we chose to.

Insulated listening is, in a way, the reverse of selective listening. In this self-protective behavior, the listener takes in and responds actively to everything the speaker says except what’s unpleasant to him or her.

Defensive listening is performed by a person when he or she interprets much or most of another person’s statements as being personal attacks. A defensive listener is apt to ignore, exclude, or fail to accurately interpret parts of a speaker’s comments.

Face-value listening can be described as aural nitpicking. That is to say, the face-value listener pays a great deal of attention to the terminology of someone else’s message and very little to the person’s intentions or feelings.

Davis, Paleg, & Fanning, Davis, M., Paleg, K., & Fanning, P. (2004). How to communicate workbook; Powerful strategies for effective communication at work and home. New York: MJF Books. identified three further ways to be a bad listener: rehearsing, identifying, and sparring. Rehearsing is the practice of planning a response to another person’s message while the message is still being delivered. Identifying takes place when a large portion of a speaker’s message triggers memories of the listener’s own experiences and makes the listener want to dive into a story of his or her own. Finally, a listener who engages in sparring attends to messages only long enough to find something to disagree with and then jabs back and forth with the speaker argumentatively.

Key Takeaway

To function well in a group, people should become familiar with both positive and negative purposes and types of listening.