5.2: Applications of Stacks

- Page ID

- 46719

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Using stacks, we can solve many applications, some of which are listed below.

Converting a decimal number into a binary number

The logic for transforming a decimal number into a binary number is as follows:

* Read a number

* Iteration (while number is greater than zero)

1. Find out the remainder after dividing the number by 2

2. Print the remainder

3. Divide the number by 2

* End the iteration

However, there is a problem with this logic. Suppose the number whose binary form we want to find is 23. Using this logic, we get the result as 11101, instead of getting 10111.

To solve this problem, we use a stack. We make use of the LIFO property of the stack. Initially we push the binary digit formed into the stack, instead of printing it directly. After the entire digit has been converted into the binary form, we pop one digit at a time from the stack and print it. Therefore we get the decimal number is converted into its proper binary form.

Algorithm:

1. Create a stack

2. Enter a decimal number which has to be converted into its equivalent binary form.

3. iteration1 (while number > 0)

3.1 digit = number % 2

3.2 Push digit into the stack

3.3 If the stack is full

3.3.1 Print an error

3.3.2 Stop the algorithm

3.4 End the if condition

3.5 Divide the number by 2

4. End iteration1

5. iteration2 (while stack is not empty)

5.1 Pop digit from the stack

5.2 Print the digit

6. End iteration2

7. STOP

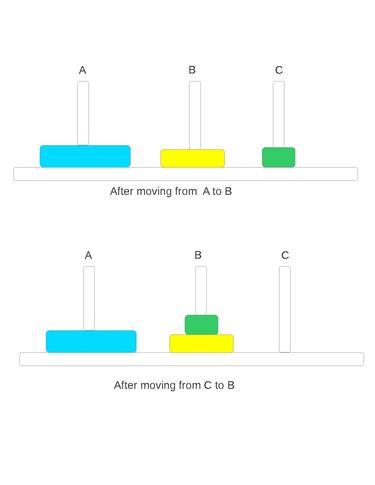

Towers of Hanoi

One of the most interesting applications of stacks can be found in solving a puzzle called Tower of Hanoi. According to an old Brahmin story, the existence of the universe is calculated in terms of the time taken by a number of monks, who are working all the time, to move 64 disks from one pole to another. But there are some rules about how this should be done, which are:

- You can move only one disk at a time.

- For temporary storage, a third pole may be used.

- You cannot place a disk of larger diameter on a disk of smaller diameter.[1]

Here we assume that A is first tower, B is second tower & C is third tower.

Output : (when there are 3 disks)

Let 1 be the smallest disk, 2 be the disk of medium size and 3 be the largest disk.

| Move disk | From peg | To peg |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | C |

| 2 | A | B |

| 1 | C | B |

| 3 | A | C |

| 1 | B | A |

| 2 | B | C |

| 1 | A | C |

Output : (when there are 4 disks)

| Move disk | From peg | To peg |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | B |

| 2 | A | C |

| 1 | B | C |

| 3 | A | B |

| 1 | C | A |

| 2 | C | B |

| 1 | A | B |

| 4 | A | C |

| 1 | B | C |

| 2 | B | A |

| 1 | C | A |

| 3 | B | C |

| 1 | A | B |

| 2 | A | C |

| 1 | B | C |

The C++ code for this solution can be implemented in two ways:

First Implementation (Without using Stacks)

Here we assume that A is first tower, B is second tower & C is third tower. (B is the intermediate)

void TowersofHanoi(int n, int a, int b, int c)

{

//Move top n disks from tower a to tower b, use tower c for intermediate storage.

if(n > 0)

{

TowersofHanoi(n-1, a, c, b); //recursion

cout << " Move top disk from tower " << a << " to tower " << b << endl ;

//Move n-1 disks from intermediate(b) to the source(a) back

TowersofHanoi(n-1, c, b, a); //recursion

}

}

[2]

Second Implementation (Using Stacks)

// Global variable, tower [1:3] are three towers

arrayStack<int> tower[4];

void TowerofHanoi(int n)

{

// Preprocessor for moveAndShow.

for (int d = n; d > 0; d--) //initialize

tower[1].push(d); //add disk d to tower 1

moveAndShow(n, 1, 2, 3); /*move n disks from tower 1 to tower 3 using

tower 2 as intermediate tower*/

}

void moveAndShow(int n, int a, int b, int c)

{

// Move the top n disks from tower a to tower b showing states.

// Use tower c for intermediate storage.

if(n > 0)

{

moveAndShow(n-1, a, c, b); //recursion

int d = tower[a].top(); //move a disc from top of tower a to top of

tower[a].pop(); //tower b

tower[b].push(d);

showState(); //show state of 3 towers

moveAndShow(n-1, c, b, a); //recursion

}

}

However complexity for above written implementations is O(\({\displaystyle 2^{n}}\)). So it's obvious that problem can only be solved for small values of n (generally n <= 30). In case of the monks, the number of turns taken to transfer 64 disks, by following the above rules, will be 18,446,744,073,709,551,615; which will surely take a lot of time!!

[1]

[2]

Expression evaluation and syntax parsing

Calculators employing reverse Polish notation use a stack structure to hold values. Expressions can be represented in prefix, postfix or infix notations. Conversion from one form of the expression to another form may be accomplished using a stack. Many compilers use a stack for parsing the syntax of expressions, program blocks etc. before translating into low level code. Most of the programming languages are context-free languages allowing them to be parsed with stack based machines.

Evaluation of an Infix Expression that is Fully Parenthesized

Input: (((2 * 5) - (1 * 2)) / (9 - 7))

Output: 4

Analysis: Five types of input characters

* Opening bracket * Numbers * Operators * Closing bracket * New line character

Data structure requirement: A character stack

Algorithm

1. Read one input character

2. Actions at end of each input

Opening brackets (2.1) Push into stack and then Go to step (1)

Number (2.2) Push into stack and then Go to step (1)

Operator (2.3) Push into stack and then Go to step (1)

Closing brackets (2.4) Pop it from character stack

(2.4.1) if it is opening bracket, then discard it, Go to step (1)

(2.4.2) Pop is used three times

The first popped element is assigned to op2

The second popped element is assigned to op

The third popped element is assigned to op1

Evaluate op1 op op2

Convert the result into character and

push into the stack

Go to step (2.4)

New line character (2.5) Pop from stack and print the answer

STOP

Result: The evaluation of the fully parenthesized infix expression is printed on the monitor as follows:

Input String: (((2 * 5) - (1 * 2)) / (9 - 7))

| Input Symbol | Stack (from bottom to top) | Operation |

|---|---|---|

| ( | ( | |

| ( | ( ( | |

| ( | ( ( ( | |

| 2 | ( ( ( 2 | |

| * | ( ( ( 2 * | |

| 5 | ( ( ( 2 * 5 | |

| ) | ( ( 10 | 2 * 5 = 10 & Push |

| - | ( ( 10 - | |

| ( | ( ( 10 - ( | |

| 1 | ( ( 10 - ( 1 | |

| * | ( ( 10 - ( 1 * | |

| 2 | ( ( 10 - ( 1 * 2 | |

| ) | ( ( 10 - 2 | 1 * 2 = 2 & Push |

| ) | ( 8 | 10 - 2 = 8 & Push |

| / | ( 8 / | |

| ( | ( 8 / ( | |

| 9 | ( 8 / ( 9 | |

| - | ( 8 / ( 9 - | |

| 9 | ( 8 / ( 9 - 7 | |

| ) | ( 8 / 2 | 9 - 7 = 2 & Push |

| ) | 4 | 8 / 2 = 4 & Push |

| New line | Empty | Pop & Print |

C Program

int main (int argc, char

struct ch *charactop;

struct integer *integertop;

char rd, op;

int i = 0, op1, op2;

charactop = cclearstack();

integertop = iclearstack();

while(1)

{

rd = argv[1][i++];

switch(rd)

{

case '+':

case '-':

case '/':

case '*':

case '(': charactop = cpush(charactop, rd);

break;

case ')': integertop = ipop (integertop, &op2);

integertop = ipop (integertop, &op1);

charactop = cpop (charactop, &op);

while(op != '(')

{

integertop = ipush (integertop, eval(op, op1, op2));

charactop = cpop (charactop, &op);

if (op != '(')

{

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op2);

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op1);

}

}

break;

case '\0': while (! cemptystack(charactop))

{

charactop = cpop(charactop, &op);

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op2);

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op1);

integertop = ipush(integertop, eval(op, op1, op2));

}

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op1);

printf("\n The final solution is: %d\n", op1);

return 0;

default: integertop = ipush(integertop, rd - '0');

}

}

}

int eval(char op, int op1, int op2)

{

switch (op)

{

case '+': return op1 + op2;

case '-': return op1 - op2;

case '/': return op1 / op2;

case '*': return op1 * op2;

}

}

Output of the program:

Input entered at the command line: (((2 * 5) - (1 * 2)) / (9 - 7)) [3]

Evaluation of Infix Expression which is not fully parenthesized

Input: (2 * 5 - 1 * 2) / (11 - 9)

Output: 4

Analysis: There are five types of input characters which are:

* Opening brackets

* Numbers

* Operators

* Closing brackets

* New line character (\n)

We do not know what to do if an operator is read as an input character. By implementing the priority rule for operators, we have a solution to this problem.

The Priority rule we should perform comparative priority check if an operator is read, and then push it. If the stack top contains an operator of prioirty higher than or equal to the priority of the input operator, then we pop it and print it. We keep on perforrming the prioirty check until the top of stack either contains an operator of lower priority or if it does not contain an operator.

Data Structure Requirement for this problem: A character stack and an integer stack

Algorithm:

1. Read an input character

2. Actions that will be performed at the end of each input

Opening brackets (2.1) Push it into stack and then Go to step (1)

Digit (2.2) Push into stack, Go to step (1)

Operator (2.3) Do the comparative priority check

(2.3.1) if the character stack's top contains an operator with equal

or higher priority, then pop it into op

Pop a number from integer stack into op2

Pop another number from integer stack into op1

Calculate op1 op op2 and push the result into the integer

stack

Closing brackets (2.4) Pop from the character stack

(2.4.1) if it is an opening bracket, then discard it and Go to

step (1)

(2.4.2) To op, assign the popped element

Pop a number from integer stack and assign it op2

Pop another number from integer stack and assign it

to op1

Calculate op1 op op2 and push the result into the integer

stack

Convert into character and push into stack

Go to the step (2.4)

New line character (2.5) Print the result after popping from the stack

STOP

Result: The evaluation of an infix expression that is not fully parenthesized is printed as follows:

Input String: (2 * 5 - 1 * 2) / (11 - 9)

| Input Symbol | Character Stack (from bottom to top) | Integer Stack (from bottom to top) | Operation performed |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( | ( | ||

| 2 | ( | 2 | |

| * | ( * | Push as * has higher priority | |

| 5 | ( * | 2 5 | |

| - | ( * | Since '-' has less priority, we do 2 * 5 = 10 | |

| ( - | 10 | We push 10 and then push '-' | |

| 1 | ( - | 10 1 | |

| * | ( - * | 10 1 | Push * as it has higher priority |

| 2 | ( - * | 10 1 2 | |

| ) | ( - | 10 2 | Perform 1 * 2 = 2 and push it |

| ( | 8 | Pop - and 10 - 2 = 8 and push, Pop ( | |

| / | / | 8 | |

| ( | / ( | 8 | |

| 11 | / ( | 8 11 | |

| - | / ( - | 8 11 | |

| 9 | / ( - | 8 11 9 | |

| ) | / | 8 2 | Perform 11 - 9 = 2 and push it |

| New line | 4 | Perform 8 / 2 = 4 and push it | |

| 4 | Print the output, which is 4 |

C Program

int main (int argc, char *argv[])

{

struct ch *charactop;

struct integer *integertop;

char rd, op;

int i = 0, op1, op2;

charactop = cclearstack();

integertop = iclearstack();

while(1)

{

rd = argv[1][i++];

switch(rd)

{

case '+':

case '-':

case '/':

case '*': while ((charactop->data != '(') && (!cemptystack(charactop)))

{

if(priority(rd) > (priority(charactop->data))

break;

else

{

charactop = cpop(charactop, &op);

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op2);

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op1);

integertop = ipush(integertop, eval(op, op1, op2);

}

}

charactop = cpush(charactop, rd);

break;

case '(': charactop = cpush(charactop, rd);

break;

case ')': integertop = ipop (integertop, &op2);

integertop = ipop (integertop, &op1);

charactop = cpop (charactop, &op);

while(op != '(')

{

integertop = ipush (integertop, eval(op, op1, op2);

charactop = cpop (charactop, &op);

if (op != '(')

{

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op2);

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op1);

}

}

break;

case '\0': while (!= cemptystack(charactop))

{

charactop = cpop(charactop, &op);

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op2);

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op1);

integertop = ipush(integertop, eval(op, op1, op2);

}

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op1);

printf("\n The final solution is: %d", op1);

return 0;

default: integertop = ipush(integertop, rd - '0');

}

}

}

int eval(char op, int op1, int op2)

{

switch (op)

{

case '+': return op1 + op2;

case '-': return op1 - op2;

case '/': return op1 / op2;

case '*': return op1 * op2;

}

}

int priority (char op)

{

switch(op)

{

case '^':

case '$': return 3;

case '*':

case '/': return 2;

case '+':

case '-': return 1;

}

}

Output of the program:

Input entered at the command line: (2 * 5 - 1 * 2) / (11 - 9)

Output: 4 [3]

Evaluation of Prefix Expression

Input: x + 6 * ( y + z ) ^ 3

Output:' 4

Analysis: There are three types of input characters

* Numbers

* Operators

* New line character (\n)

Data structure requirement: A character stack and an integer stack

Algorithm:

1. Read one character input at a time and keep pushing it into the character stack until the new

line character is reached

2. Perform pop from the character stack. If the stack is empty, go to step (3)

Number (2.1) Push in to the integer stack and then go to step (1)

Operator (2.2) Assign the operator to op

Pop a number from integer stack and assign it to op1

Pop another number from integer stack

and assign it to op2

Calculate op1 op op2 and push the output into the integer

stack. Go to step (2)

3. Pop the result from the integer stack and display the result

Result: The evaluation of prefix expression is printed as follows:

Input String: / - * 2 5 * 1 2 - 11 9

| Input Symbol | Character Stack (from bottom to top) | Integer Stack (from bottom to top) | Operation performed |

|---|---|---|---|

| / | / | ||

| - | / | ||

| * | / - * | ||

| 2 | / - * 2 | ||

| 5 | / - * 2 5 | ||

| * | / - * 2 5 * | ||

| 1 | / - * 2 5 * 1 | ||

| 2 | / - * 2 5 * 1 2 | ||

| - | / - * 2 5 * 1 2 - | ||

| 11 | / - * 2 5 * 1 2 - 11 | ||

| 9 | / - * 2 5 * 1 2 - 11 9 | ||

| \n | / - * 2 5 * 1 2 - 11 | 9 | |

| / - * 2 5 * 1 2 - | 9 11 | ||

| / - * 2 5 * 1 2 | 2 | 11 - 9 = 2 | |

| / - * 2 5 * 1 | 2 2 | ||

| / - * 2 5 * | 2 2 1 | ||

| / - * 2 5 | 2 2 | 1 * 2 = 2 | |

| / - * 2 | 2 2 5 | ||

| / - * | 2 2 5 2 | ||

| / - | 2 2 10 | 5 * 2 = 10 | |

| / | 2 8 | 10 - 2 = 8 | |

| Stack is empty | 4 | 8 / 2 = 4 | |

| Stack is empty | Print 4 |

C Program

int main (int argc, char *argv[])

{

struct ch *charactop = NULL;

struct integer *integertop = NULL;

char rd, op;

int i = 0, op1, op2;

charactop = cclearstack();

integertop = iclearstack();

rd = argv[1][i];

while(rd != '\0')

{

charactop = cpush(charactop, rd);

rd = argv[1][i++];

}

while(!emptystack(charactop))

{

charactop = cpop(charactop, rd);

switch(rd)

{

case '+':

case '-':

case '/':

case '*':

op = rd;

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op2);

integertop = ipop(integertop, &op1);

integertop = ipush(integertop, eval(op, op1, op2));

break;

default: integertop = ipush(integertop, rd - '0');

}

}

}

int eval(char op, int op1, int op2)

{

switch (op)

{

case '+': return op1 + op2;

case '-': return op1 - op2;

case '/': return op1 / op2;

case '*': return op1 * op2;

}

}

int priority (char op)

{

switch(op)

{

case '^':

case '$': return 3;

case '*':

case '/': return 2;

case '+':

case '-': return 1;

}

}

Output of the program:

Input entered at the command line: / - * 2 5 * 1 2 - 11 9

Output: 4 [3]

Conversion of an Infix expression that is fully parenthesized into a Postfix expression

Input: (((8 + 1) - (7 - 4)) / (11 - 9))

Output: 8 1 + 7 4 - - 11 9 - /

Analysis: There are five types of input characters which are:

* Opening brackets

* Numbers

* Operators

* Closing brackets

* New line character (\n)

Requirement: A character stack

Algorithm:

1. Read an character input

2. Actions to be performed at end of each input

Opening brackets (2.1) Push into stack and then Go to step (1)

Number (2.2) Print and then Go to step (1)

Operator (2.3) Push into stack and then Go to step (1)

Closing brackets (2.4) Pop it from the stack

(2.4.1) If it is an operator, print it, Go to step (1)

(2.4.2) If the popped element is an opening bracket,

discard it and go to step (1)

New line character (2.5) STOP

Therefore, the final output after conversion of an infix expression to a postfix expression is as follows:

| Input | Operation | Stack (after op) | Output on monitor |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( | (2.1) Push operand into stack | ( | |

| ( | (2.1) Push operand into stack | ( ( | |

| ( | (2.1) Push operand into stack | ( ( ( | |

| 8 | (2.2) Print it | 8 | |

| + | (2.3) Push operator into stack | ( ( ( + | 8 |

| 1 | (2.2) Print it | 8 1 | |

| ) | (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '+' print it | ( ( ( | 8 1 + |

| (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '(' we ignore it and read next character | ( ( | 8 1 + | |

| - | (2.3) Push operator into stack | ( ( - | |

| ( | (2.1) Push operand into stack | ( ( - ( | |

| 7 | (2.2) Print it | 8 1 + 7 | |

| - | (2.3) Push the operator in the stack | ( ( - ( - | |

| 4 | (2.2) Print it | 8 1 + 7 4 | |

| ) | (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '-' print it | ( ( - ( | 8 1 + 7 4 - |

| (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '(' we ignore it and read next character | ( ( - | ||

| ) | (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '-' print it | ( ( | 8 1 + 7 4 - - |

| (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '(' we ignore it and read next character | ( | ||

| / | (2.3) Push the operand into the stack | ( / | |

| ( | (2.1) Push into the stack | ( / ( | |

| 11 | (2.2) Print it | 8 1 + 7 4 - - 11 | |

| - | (2.3) Push the operand into the stack | ( / ( - | |

| 9 | (2.2) Print it | 8 1 + 7 4 - - 11 9 | |

| ) | (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '-' print it | ( / ( | 8 1 + 7 4 - - 11 9 - |

| (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '(' we ignore it and read next character | ( / | ||

| ) | (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '/' print it | ( | 8 1 + 7 4 - - 11 9 - / |

| (2.4) Pop from the stack: Since popped element is '(' we ignore it and read next character | Stack is empty | ||

| New line character | (2.5) STOP |

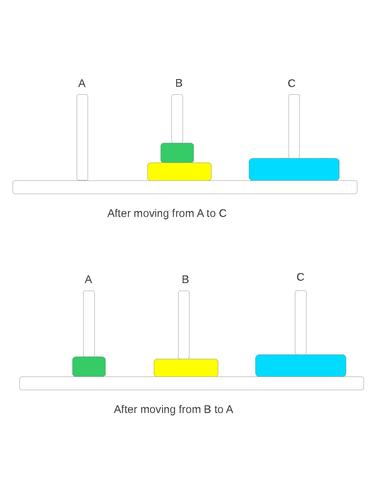

Rearranging railroad cars

Problem Description

It's a very nice application of stacks. Consider that a freight train has n railroad cars. Each to be left at different station. They're numbered 1 through n & freight train visits these stations in order n through 1. Obviously, the railroad cars are labeled by their destination.To facilitate removal of the cars from the train, we must rearrange them in ascending order of their number(i.e. 1 through n). When cars are in this order, they can be detached at each station. We rearrange cars at a shunting yard that has input track, output track & k holding tracks between input & output tracks(i.e. holding track).

Solution Strategy

To rearrange cars, we examine the cars on the input from front to back. If the car being examined is next one in the output arrangement, we move it directly to output track. If not, we move it to the holding track & leave it there until it's time to place it to the output track. The holding tracks operate in a LIFO manner as the cars enter & leave these tracks from top. When rearranging cars only following moves are permitted:

- A car may be moved from front (i.e. right end) of the input track to the top of one of the holding tracks or to the left end of the output track.

- A car may be moved from the top of holding track to left end of the output track.

The figure shows a shunting yard with k = 3, holding tracks H1, H2 & H3, also n = 9. The n cars of freight train begin in the input track & are to end up in the output track in order 1 through n from right to left. The cars initially are in the order 5,8,1,7,4,2,9,6,3 from back to front. Later cars are rearranged in desired order.

A Three Track Example

- Consider the input arrangement from figure, here we note that the car 3 is at the front, so it can't be output yet, as it to be preceded by cars 1 & 2. So car 3 is detached & moved to holding track H1.

- The next car 6 can't be output & it is moved to holding track H2. Because we have to output car 3 before car 6 & this will not possible if we move car 6 to holding track H1.

- Now it's obvious that we move car 9 to H3.

The requirement of rearrangement of cars on any holding track is that the cars should be preferred to arrange in ascending order from top to bottom.

- So car 2 is now moved to holding track H1 so that it satisfies the previous statement. If we move car 2 to H2 or H3, then we've no place to move cars 4,5,7,8.The least restrictions on future car placement arise when the new car λ is moved to the holding track that has a car at its top with smallest label Ψ such that λ < Ψ. We may call it an assignment rule to decide whether a particular car belongs to a specific holding track.

- When car 4 is considered, there are three places to move the car H1,H2,H3. The top of these tracks are 2,6,9.So using above mentioned Assignment rule, we move car 4 to H2.

- The car 7 is moved to H3.

- The next car 1 has the least label, so it's moved to output track.

- Now it's time for car 2 & 3 to output which are from H1(in short all the cars from H1 are appended to car 1 on output track).

The car 4 is moved to output track. No other cars can be moved to output track at this time.

- The next car 8 is moved to holding track H1.

- Car 5 is output from input track. Car 6 is moved to output track from H2, so is the 7 from H3,8 from H1 & 9 from H3.

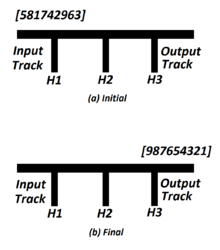

Quicksort

Sorting means arranging a group of elements in a particular order. Be it ascending or descending, by cardinality or alphabetical order or variations thereof. The resulting ordering possibilities will only be limited by the type of the source elements.

Quicksort is an algorithm of the divide and conquer type. In this method, to sort a set of numbers, we reduce it to two smaller sets, and then sort these smaller sets.

This can be explained with the help of the following example:

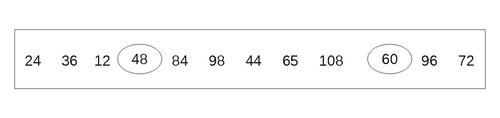

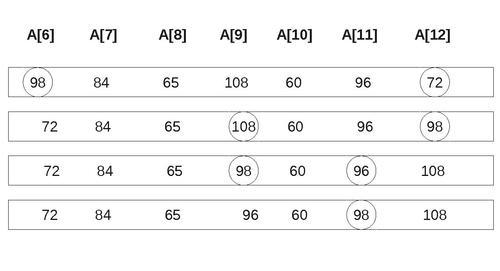

Suppose A is a list of the following numbers:

In the reduction step, we find the final position of one of the numbers. In this case, let us assume that we have to find the final position of 48, which is the first number in the list.

To accomplish this, we adopt the following method. Begin with the last number, and move from right to left. Compare each number with 48. If the number is smaller than 48, we stop at that number and swap it with 48.

In our case, the number is 24. Hence, we swap 24 and 48.

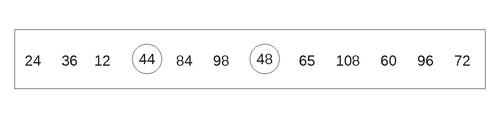

The numbers 96 and 72 to the right of 48, are greater than 48. Now beginning with 24, scan the numbers in the opposite direction, that is from left to right. Compare every number with 48 until you find a number that is greater than 48.

In this case, it is 60. Therefore we swap 48 and 60.

Note that the numbers 12, 24 and 36 to the left of 48 are all smaller than 48. Now, start scanning numbers from 60, in the right to left direction. As soon as you find lesser number, swap it with 48.

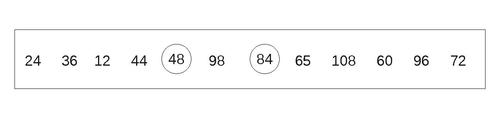

In this case, it is 44. Swap it with 48. The final result is:

Now, beginning with 44, scan the list from left to right, until you find a number greater than 48.

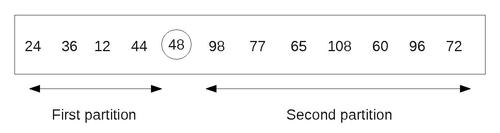

Such a number is 84. Swap it with 48. The final result is:

Now, beginning with 84, traverse the list from right to left, until you reach a number lesser than 48. We do not find such a number before reaching 48. This means that all the numbers in the list have been scanned and compared with 48. Also, we notice that all numbers less than 48 are to the left of it, and all numbers greater than 48, are to its right.

The final partitions look as follows:

Therefore, 48 has been placed in its proper position and now our task is reduced to sorting the two partitions. This above step of creating partitions can be repeated with every partition containing 2 or more elements. As we can process only a single partition at a time, we should be able to keep track of the other partitions, for future processing.

This is done by using two stacks called LOWERBOUND and UPPERBOUND, to temporarily store these partitions. The addresses of the first and last elements of the partitions are pushed into the LOWERBOUND and UPPERBOUND stacks respectively. Now, the above reduction step is applied to the partitions only after its boundary values are popped from the stack.

We can understand this from the following example:

Take the above list A with 12 elements. The algorithm starts by pushing the boundary values of A, that is 1 and 12 into the LOWERBOUND and UPPERBOUND stacks respectively. Therefore the stacks look as follows:

LOWERBOUND: 1 UPPERBOUND: 12

To perform the reduction step, the values of the stack top are popped from the stack. Therefore, both the stacks become empty.

LOWERBOUND: {empty} UPPERBOUND: {empty}

Now, the reduction step causes 48 to be fixed to the 5th position and creates two partitions, one from position 1 to 4 and the other from position 6 to 12. Hence, the values 1 and 6 are pushed into the LOWERBOUND stack and 4 and 12 are pushed into the UPPERBOUND stack.

LOWERBOUND: 1, 6 UPPERBOUND: 4, 12

For applying the reduction step again, the values at the stack top are popped. Therefore, the values 6 and 12 are popped. Therefore the stacks look like:

LOWERBOUND: 1 UPPERBOUND: 4

The reduction step is now applied to the second partition, that is from the 6th to 12th element.

After the reduction step, 98 is fixed in the 11th position. So, the second partition has only one element. Therefore, we push the upper and lower boundary values of the first partition onto the stack. So, the stacks are as follows: LOWERBOUND: 1, 6 UPPERBOUND: 4, 10

The processing proceeds in the following way and ends when the stacks do not contain any upper and lower bounds of the partition to be processed, and the list gets sorted.

The Stock Span Problem

In the stock span problem, we will solve a financial problem with the help of stacks.

Suppose, for a stock, we have a series of n daily price quotes, the span of the stock's price on a particular day is defined as the maximum number of consecutive days for which the price of the stock on the current day is less than or equal to its price on that day.

An algorithm which has Quadratic Time Complexity

Input: An array P with n elements

Output: An array S of n elements such that S[i] is the largest integer k such that k <= i + 1 and P[j] <= P[i] for j = i - k + 1,.....,i

Algorithm:

1. Initialize an array P which contains the daily prices of the stocks

2. Initialize an array S which will store the span of the stock

3. for i = 0 to i = n - 1

3.1 Initialize k to zero

3.2 Done with a false condition

3.3 repeat

3.3.1 if ( P[i - k] <= P[i)] then

Increment k by 1

3.3.2 else

Done with true condition

3.4 Till (k > i) or done with processing

Assign value of k to S[i] to get the span of the stock

4. Return array S

Now, analyzing this algorithm for running time, we observe:

- We have initialized the array S at the beginning and returned it at the end. This is a constant time operation, hence takes O(n) time

- The repeat loop is nested within the for loop. The for loop, whose counter is i is executed n times. The statements which are not in the repeat loop, but in the for loop are executed n times. Therefore these statements and the incrementing and condition testing of i take O(n) time.

- In repetition of i for the outer for loop, the body of the inner repeat loop is executed maximum i + 1 times. In the worst case, element S[i] is greater than all the previous elements. So, testing for the if condition, the statement after that, as well as testing the until condition, will be performed i + 1 times during iteration i for the outer for loop. Hence, the total time taken by the inner loop is O(n(n + 1)/2), which is O(\({\displaystyle n^{2}}\))

The running time of all these steps is calculated by adding the time taken by all these three steps. The first two terms are O(\({\displaystyle n}\)) while the last term is O(\({\displaystyle n^{2}}\)). Therefore the total running time of the algorithm is O(\({\displaystyle n^{2}}\)).

An algorithm that has Linear Time Complexity

In order to calculate the span more efficiently, we see that the span on a particular day can be easily calculated if we know the closest day before i, such that the price of the stocks on that day was higher than the price of the stocks on the present day. If there exists such a day, we can represent it by h(i) and initialize h(i) to be -1.

Therefore the span of a particular day is given by the formula, s = i - h(i).

To implement this logic, we use a stack as an abstract data type to store the days i, h(i), h(h(i)) and so on. When we go from day i-1 to i, we pop the days when the price of the stock was less than or equal to p(i) and then push the value of day i back into the stack.

Here, we assume that the stack is implemented by operations that take O(1) that is constant time. The algorithm is as follows:

Input: An array P with n elements and an empty stack N

Output: An array S of n elements such that P[i] is the largest integer k such that k <= i + 1 and P[y] <= P[i] for j = i - k + 1,.....,i

Algorithm:

1. Initialize an array P which contains the daily prices of the stocks

2. Initialize an array S which will store the span of the stock

3. for i = 0 to i = n - 1

3.1 Initialize k to zero

3.2 Done with a false condition

3.3 while not (Stack N is empty or done with processing)

3.3.1 if ( P[i] >= P[N.top())] then

Pop a value from stack N

3.3.2 else

Done with true condition

3.4 if Stack N is empty

3.4.1 Initialize h to -1

3.5 else

3.5.1 Initialize stack top to h

3.5.2 Put the value of h - i in S[i]

3.5.3 Push the value of i in N

4. Return array S

Now, analyzing this algorithm for running time, we observe:

- We have initialized the array S at the beginning and returned it at the end. This is a constant time operation, hence takes O(n) time

- The while loop is nested within the for loop. The for loop, whose counter is i is executed n times. The statements which are not in the repeat loop, but in the for loop are executed n times. Therefore these statements and the incrementing and condition testing of i take O(n) time.

- Now, observe the inner while loop during i repetitions of the for loop. The statement done with a true condition is done at most once, since it causes an exit from the loop. Let us say that t(i) is the number of times statement Pop a value from stack N is executed. So it becomes clear that while not (Stack N is empty or done with processing) is tested maximum t(i) + 1 times.

- Adding the running time of all the operations in the while loop, we get:

\[{\displaystyle \sum _{i=0}^{n-1}t(i)+1}\nonumber\]

- An element once popped from the stack N is never pushed back into it. Therefore,

\[{\displaystyle \sum _{i=1}^{n-1}t(i)}\nonumber\]

So, the running time of all the statements in the while loop is O(\({\displaystyle n}\))

The running time of all the steps in the algorithm is calculated by adding the time taken by all these steps. The run time of each step is O(\({\displaystyle n}\)). Hence the running time complexity of this algorithm is O(\({\displaystyle n}\)).

Related Links

- Stack (Wikipedia)