3.6.3: Uncountable sets

- Page ID

- 10905

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)On the other hand, R is uncountable. It is not possible to make an infinite list that con- tains every real number. It is not even possible to make a list that contains every real number between zero and one. Another way of saying this is that every infinite list of real numbers between zero and one, no matter how it is constructed, leaves something out. To see why this is true, imagine such a list, displayed in an infinitely long column. Each row contains one number, which has an infinite number of digits after the decimal point. Since it is a number between zero and one, the only digit before the decimal point is zero. For example, the list might look like this:

0.90398937249879561297927654857945...

0.12349342094059875980239230834549...

0.22400043298436234709323279989579...

0.50000000000000000000000000000000...

0.77743449234234876990120909480009...

0.77755555588888889498888980000111...

0.12345678888888888888888800000000...

0.34835440009848712712123940320577...

0.93473244447900498340999990948900...

...

This is only (a small part of) one possible list. How can we be certain that every such list leaves out some real number between zero and one? The trick is to look at the digits shown in bold face. We can use these digits to build a number that is not in the list. Since the first number in the list has a 9 in the first position after the decimal point, we know that this number cannot equal any number of, for example, the form 0.4.... Since the second number has a 2 in the second position after the decimal point, neither of the first two numbers in the list is equal to any number that begins with 0.44.... Since the third number has a 4 in the third position after the decimal point, none of the first three numbers in the list is equal to any number that begins 0.445.... We can continue to construct a number in this way, and we end up with a number that is different from every number in the list. The \(n^{\text { th }}\) digit of the number we are building must differ from the \(n^{t h}\)digit of the \(n^{\text { th }}\) number in the list. These are the digits shown in bold face in the above

list. To be definite, I use a 5 when the corresponding boldface number is 4, and otherwise I use a 4. For the list shown above, this gives a number that begins 0.44544445.... The number constructed in this way is not in the given list, so the list is incomplete. The same construction clearly works for any list of real numbers between zero and one. No such list can be a complete listing of the real numbers between zero and one, and so there can be no complete listing of all real numbers. We conclude that the set R is uncountable.

The technique used in this argument is called diagonalization. It is named after the fact that the bold face digits in the above list lie along a diagonal line.

Proofs by diagonalisation are not a part of Reasoning & Logic. You should be able to prove a set is countably infinite (by finding a bijection from N to the set), but you will not be asked to prove a set is uncountable. We leave that for the course Automata, Languages, and Computability later in your curriculum.

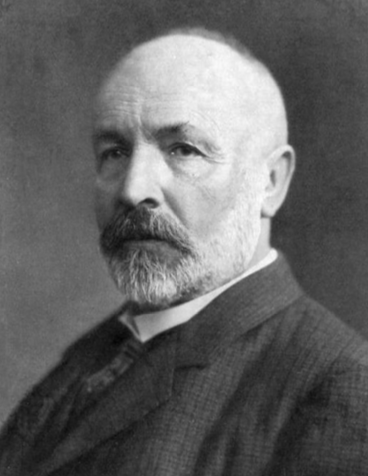

This proof was discovered by a mathematician named Georg Cantor, who caused quite a fuss in the nineteenth century when he came up with the idea that there are different kinds of infinity. Since then, his notion of using one-to-one correspondence to define the cardinalities of infinite sets has been accepted. Mathematicians now consider it almost intuitive that N, Z, and Q have the same cardinality while R has a strictly larger cardinality.

To say that Georg Cantor (1845–1918) caused a fuss in mathematics is the least you can say. Cantor’s theory of transfinite numbers was originally regarded as so counter-intuitive—even shocking—that it encountered resistance from mathematical contemporaries. Like Frege, Cantor was a German mathematician contributing to logic and set theory. Like Peirce, Cantor’s ideas did not find acceptance until later in his life. In 1904, the Royal Society awarded Cantor its Sylvester Medal, the highest honour it can confer for work in mathematics.

Source: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Cantor.

Theorem 4.9.

Suppose that X is an uncountable set, and that K is a countable subset of X. Then the set X ∖ K is uncountable.

Proof. Let X be an uncountable set. Let K ⊆ X, and suppose that K is countable. LetL = X ∖ K. We want to show that L is uncountable. Suppose that L is countable. We will show that this assumption leads to a contradiction.

Note that X = K ∪ (X ∖ K) = K ∪ L. You will show in Exercise 11 of this section that the union of two countable sets is countable. Since X is the union of the countable sets Kand L, it follows that X is countable. But this contradicts the fact that X is uncountable. This contradiction proves the theorem.

In the proof, both q and ¬q are shown to follow from the assumptions, where q is the statement “X is countable”. The statement q is shown to follow from the assumption that X ∖ K is countable. The statement ¬q is true by assumption. Since q and ¬q cannot both be true, at least one of the assumptions must be false. The only assumption that can be false is the assumption that X ∖ K is countable.

This theorem, by the way, has the following easy corollary. (A corollary is a theorem that follows easily from another, previously proved theorem.)

Corollary 4.10.

The set of irrational real numbers is uncountable.

Proof. Let I be the set of irrational real numbers. By definition, I = R ∖ Q. We have already shown that R is uncountable and that Q is countable, so the result follows immediately from the previous theorem.

You might still think that R is as big as things get, that is, that any infinite set is in one-to-one correspondence with R or with some subset of R. In fact, though, if X is any set then it’s possible to find a set that has strictly larger cardinality than X. In fact,P(X) is such a set. A variation of the diagonalization technique can be used to show that there is no one-to-one correspondence between X and P(X). Note that this is obvious for finite sets, since for a finite set \(X,|\mathcal{P}(X)|=2^{|X|},\) which is larger than \(|X| .\) The point of the theorem is that it is true even for infinite sets.

Theorem 4.11.

Let X be any set. Then there is no one-to-one correspondence between X and P(X).

Proof. Given an arbitrary function f : X → P(X), we can show that f is not onto. Since a one-to-one correspondence is both one-to-one and onto, this shows that f is not a one- to-one correspondence.

Recall that P(X) is the set of subsets of X. So, for each x ∈ X, f(x) is a subset of X. We have to show that no matter how f is defined, there is some subset of X that is not in the image of f.

Given \(f,\) we define \(A\) to be the set \(A=\{x \in X | x \notin f(x)\} .\) The test \(^{\prime} x \notin f(x)^{\prime \prime}\) makes sense because f (x) is a set. Since A ⊆ X, we have that A ∈ P(X). However, A is not in the image of \(f .\) That is, for every \(y \in X, A \neq f(y) .^{7}\) To see why this is true, let \(y\) be any element of \(X .\) There are two cases to consider. Either \(y \in f(y)\) or \(y \notin f(y)\). We show that whichever case holds, \(A \neq f(y) .\) If it is true that \(y \in f(y),\) then by the definition of \(A, y \notin A .\) since \(y \in f(y)\) but \(y \notin A, f(y)\) and \(A\) do not have the same elements and therefore are not equal. On the other hand, suppose that \(y \notin f(y) .\) Again, by the definition of \(A,\) this implies that \(y \in A .\) since \(y \notin f(y)\) but \(y \in A, f(y)\) and \(A\) do not have the same elements and therefore are not equal. In either case, \(A \neq f(y) .\) Since this is true for any y ∈ X, we conclude that A is not in the image of f and therefore f is not a one-to-one correspondence.

From this theorem, it follows that there is no one-to-one correspondence between R and P(R). The cardinality of P(R) is strictly bigger than the cardinality of R. But it doesn’t stop there. P(P(R)) has an even bigger cardinality, and the cardinality ofP(P(P(R))) is bigger still. We could go on like this forever, and we still won’t have exhausted all the possible cardinalities. If we let X be the infinite union R ∪ P(R) ∪P(P(R)) ∪ · · · , then X has larger cardinality than any of the sets in the union. And then there’s P(X), P(P(X)), X ∪ P(X) ∪ P(P(X)) ∪ · · · . There is no end to this. There is no upper limit on possible cardinalities, not even an infinite one! We have counted past infinity.