12.2: Types of Subsidies and Incentive Programs

- Page ID

- 47820

Types of Subsidies and Incentive Programs

Before you get too deeply into this lesson, have a look at the Glossary page from the DSIRE website. Focus on the first section of the page, which defines a number of types of financial incentives. The definitions here aren't too in-depth, but reviewing them will get you familiar with the language of different types of incentives. If you are interested, the section of the page on "Rules, Regulations and Policies" is also worth a look to give you some appreciation for the truly dizzying array of ways that governments at various levels (state, federal, and local) are trying to encourage the use of renewable energy resources, particularly for the production of electricity.

In general, DSIRE is a very good resource for learning about renewable energy and energy-efficiency incentives in the United States. The following video provides a quick tour of some of the most useful information on the DSIRE website. (Note: as of this writing the DSIRE website was undergoing some major revisions, but the structure of the web site itself does not appear to have changed that much. It is worth some time wandering around that website to see what information is available.)

Video: DSIRE Video (4:20)

We'll categorize subsidies and incentives into a few broad categories:

- Tax incentives

Tax incentives include credits, deductions and exemptions. Understanding the difference between the three is important. A "credit" represents a rebate on your tax bill, while a "deduction" represents a reduction in your taxable income. An "exemption" is simply an excusal from paying a certain category of tax (you could look at an exemption as a credit or deduction equal to 100%). There are relatively few tax exemptions for renewable energy as compared to the number of different tax credits or deductions. So, the difference between a credit and deduction comes down to whether the subsidy is applied pre-tax or post-tax. Recall our discussion of the pro forma profit and loss statement from Lesson 8. The depreciation allowance for invested capital is a good example of a deduction, since depreciation is subtracted from pre-tax net income. A credit is really no different than a direct payment since it is applied as a reduction to taxes paid, or as an adder to after-tax income (the two are mathematically equivalent).

As a simple example, suppose that a project had a pre-tax income of $100 in some year, and faced a 35% tax rate. Without any subsidies, the tax bill for the project would be $35, and its after-tax income would be $65. Now, suppose that the project could take advantage of a tax deduction or a tax credit, both of which were equal to 20%. If the subsidy were structured as a credit, the 20% would be subtracted from the 35% tax rate, for a net tax rate of 15%. The tax bill for the project would fall to $15 (15% of $100) and after-tax income would rise to $85.

Now, if the subsidy were structured as a deduction, the tax analysis would go like this:- The subsidy would reduce taxable income by 20%, so taxable income in this case would fall to $80.

- The 35% tax rate would be applied to the reduced taxable income. So total taxes for our hypothetical project would be 35% × $80 = $28.

- After-tax income would be $100 - $28 = $72.

- Loan programs

Loan programs are generally advantageous because they can lower the cost of debt faced by an energy project or investor, which in turn will lower the WACC, sometimes dramatically. There are basically two flavors of loan programs. Many governmental entities offer low-interest or zero-interest loans for renewable energy projects. There are also loan guarantees, which reduce the cost of debt by providing a sort of insurance in case the project does not perform as anticipated or if the project owner defaults on her debts. Loan guarantees are often used by governments to convince private investors to purchase debt being offered by companies promoting technologies that have not yet been market tested. Ultimately the loan guarantee has the same effect as the low-interest or zero-interest loan - it can lower the cost of debt and thus the WACC. - Rebates and Grants

Rebates and Grants, although technically different, work much the same way. Both act to offset the capital cost of renewable energy technologies. There are some technical differences - for example in some jurisdictions a rebate is actually considered income that could be taxed, whereas a grant is exempt from any income tax. - Feed-in Tariffs

Feed-in Tariffs (or what DSIRE calls "performance-based incentives") are payments to the owners of qualifying energy projects for each unit of energy produced from those projects. Feed-in tariffs actually have much the same effect on a project's financial position as a tax credit. Feed-in tariffs are not used very often in the United States, but have become quite common in Europe. Germany, for example, had for years set a very high feed-in tariff for solar photovoltaics. As a result, Germany became one of the world's largest markets for solar energy despite having a climate that, compared especially to hot desert climates, was not all that advantageous for solar.

The Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS, sometimes called Clean Energy Standards) also deserves some mention, since it has been a popular mechanism to support renewable energy development in the United States in particular. Please have a look at Section III of "The Cost of the Alternative Energy Portfolio Standard in Pennsylvania" (reading on Canvas), which describes the RPS in one particular U.S. state, Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania's RPS is typical of how many such portfolio standards work. The reading also provides an overview of RPS policies in some other states. (You might notice that Pennsylvania qualifies some fossil fuels as "alternative energy sources" under its RPS, which demonstrates that RPS policies are not always equivalent to low-carbon policies.)

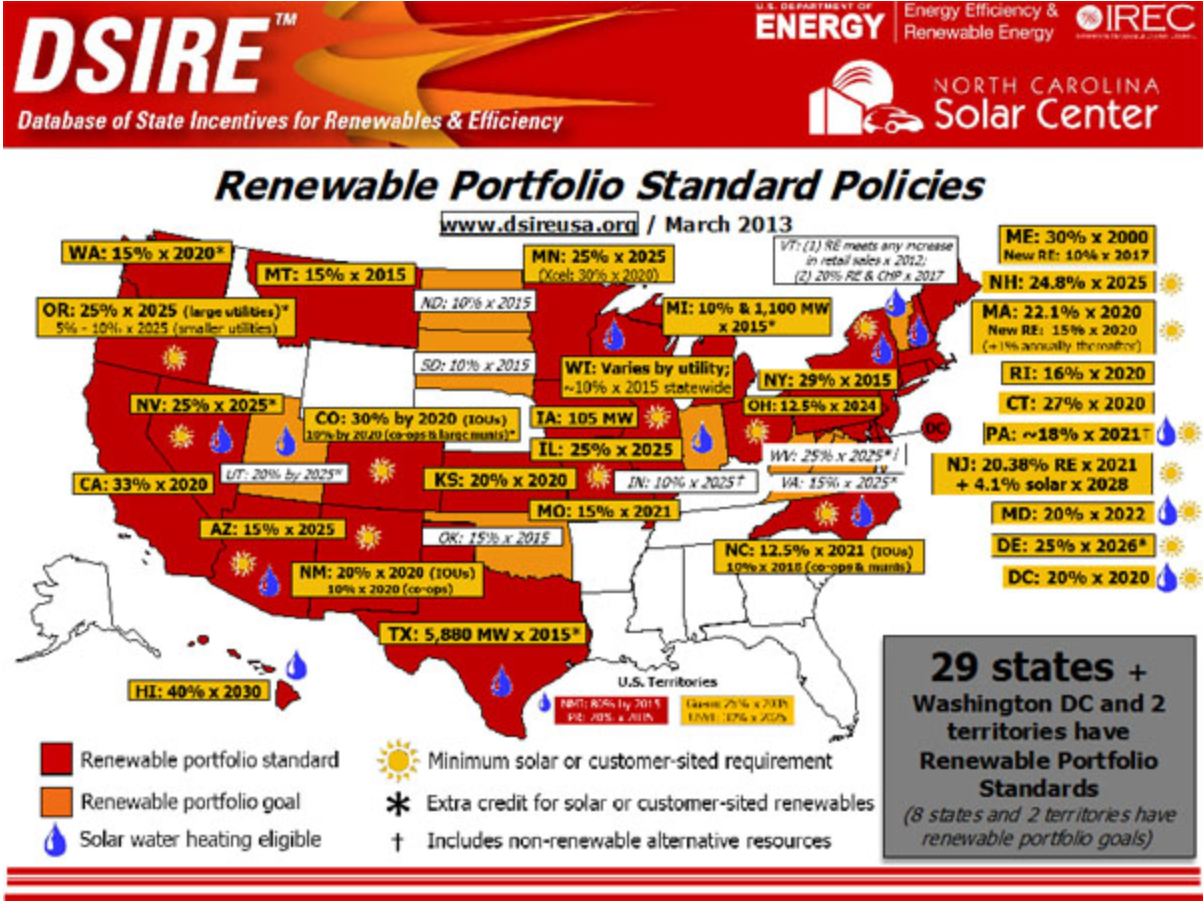

\(Figure \text { } 12.1\): Renewable Portfolio Standard Policies.

The RPS is basically a quota system for renewable energy and has been applied mostly to electricity. More than half of U.S. states have adopted some form of RPS, as shown in \(Figure \text { } 12.1\), taken from the DSIRE website. Some countries have adopted policies for blending petroleum-based transportation fuels with biomass-based fuels (such as the Renewable Fuels Standard in the U.S., which you can read about through the U.S. Environmental Protextion Agency, but our discussion here will focus on portfolio standards for alternative electricity generation technologies. Rather than subsidizing renewables through financial mechanisms as we have already discussed, RPS sets quantity targets for market penetration by designated alternative electricity generation resources within some geographic territory, like a state or sometimes an entire country. Typical technologies targeted under RPS include wind, solar, biomass, and so forth. The way that RPS systems typically work in practice is that electric utilities can either build the required amount of alternative power generation technologies themselves, or they can contract with a separate company to make those investments. Companies that build renewable energy projects can register those projects in a jurisdiction with the RPS to generate tradeable renewable energy credits (RECs). The RECs can then be sold to electric utilities who can use those credits to meet their renewable energy targets.

You can find more information on REC prices through the NREL REC report assigned as part of this week's reading. The data in the report makes a distinction between "voluntary" REC prices and "compliance" prices. Some states or areas have RPS targets that are not mandated by law, while in other states utilities face penalties if they do not comply with meeting their RPS targets.