4: Discrete -Time Signals and Systems

- Page ID

- 96272

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Study of Discrete-Time signals.

Mathematically, analog signals are functions having as their independent variables continuous quantities, such as space and time. Discrete-time signals are functions defined on the integers; they are sequences. As with analog signals, we seek ways of decomposing discrete-time signals into simpler components. Because this approach leads to a better understanding of signal structure, we can exploit that structure to represent information (create ways of representing information with signals) and to extract information (retrieve the information thus represented). For symbolic-valued signals, the approach is different: We develop a common representation of all symbolic-valued signals so that we can embody the information they contain in a unified way. From an information representation perspective, the most important issue becomes, for both real-valued and symbolic-valued signals, efficiency: what is the most parsimonious and compact way to represent information so that it can be extracted later.

Real- and Complex-valued Signals

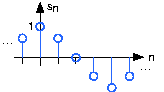

A discrete-time signal is represented symbolically as s(n) where n={...,-1,0,1,...}

We usually draw discrete-time signals as stem plots to emphasize the fact they are functions defined only on the integers. We can delay a discrete-time signal by an integer just as with analog ones. A signal delayed by m samples has the expression s(n-m).

Complex Exponentials

The most important signal is, of course, the complex exponential sequence.

\[s(n)=e^{i2\pi fn} \nonumber \]

Note that the frequency variable f is dimensionless and that adding an integer to the frequency of the discrete-time complex exponential has no effect on the signal's value.

\[e^{i2\pi (f+m)n}=e^{i2\pi fn}e^{i2\pi mn}=e^{i2\pi fn} \nonumber \]

This derivation follows because the complex exponential evaluated at an integer multiple of

Sinusoids

Discrete-time sinusoids have the obvious form

\[s(n)=A\cos (2\pi fn+\varphi ) \nonumber \]

As opposed to analog complex exponentials and sinusoids that can have their frequencies be any real value, frequencies of their discrete-time counterparts yield unique waveforms only when f lies in the interval:

\[\left ( -\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{2} \right ] \nonumber \]

This choice of frequency interval is arbitrary; we can also choose the frequency to lie in the interval [0,1). How to choose a unit-length interval for a sinusoid's frequency will become evident later.

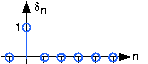

Unit Sample

The second-most important discrete-time signal is the unit sample, which is defined to be

\[\delta (n)=\begin{cases} 1 & \text{ if } n=0 \\ 0 & \text{ if } otherwise \end{cases} \nonumber \]

Examination of a discrete-time signal's plot, like that of the cosine signal shown in Figure 5.5.2, reveals that all signals consist of a sequence of delayed and scaled unit samples. Because the value of a sequence at each integer m is denoted by s(m) and the unit sample delayed to occur at m is written δ(n-m), we can decompose any signal as a sum of unit samples delayed to the appropriate location and scaled by the signal value.

\[s(n)=\sum_{m=-\infty }^{\infty }s(m)\delta (n-m) \nonumber \]

This kind of decomposition is unique to discrete-time signals, and will prove useful subsequently.

Unit Step

The unit step in discrete-time is well-defined at the origin, as opposed to the situation with analog signals.

\[u(n)=\begin{cases} 1 & \text{ if } n\geq 0 \\ 0 & \text{ if } n< 0 \end{cases} \nonumber \]

Symbolic Signals

An interesting aspect of discrete-time signals is that their values do not need to be real numbers. We do have real-valued discrete-time signals like the sinusoid, but we also have signals that denote the sequence of characters typed on the keyboard. Such characters certainly aren't real numbers, and as a collection of possible signal values, they have little mathematical structure other than that they are members of a set. More formally, each element of the symbolic-valued signal s(n) takes on one of the values {a1,...,ak} which comprise the alphabet A. This technical terminology does not mean we restrict symbols to being members of the English or Greek alphabet. They could represent keyboard characters, bytes (8-bit quantities), integers that convey daily temperature. Whether controlled by software or not, discrete-time systems are ultimately constructed from digital circuits, which consist entirely of analog circuit elements. Furthermore, the transmission and reception of discrete-time signals, like e-mail, is accomplished with analog signals and systems. Understanding how discrete-time and analog signals and systems intertwine is perhaps the main goal of this course.

Discrete-Time Systems

Discrete-time systems can act on discrete-time signals in ways similar to those found in analog signals and systems. Because of the role of software in discrete-time systems, many more different systems can be envisioned and "constructed" with programs than can be with analog signals. In fact, a special class of analog signals can be converted into discrete-time signals, processed with software, and converted back into an analog signal, all without the incursion of error. For such signals, systems can be easily produced in software, with equivalent analog realizations difficult, if not impossible, to design.

Discrete-Time System Classifications

Linearity

A discrete-time system is linear if it satisfies the properties of homogeneity (scaling) and additivity

- Scaling: \(\mathcal{T}[a x(n)] = a \mathcal{T}[x(n)] \)

- Additivity: \(\mathcal{T}[x_1(n) + x_2(n)] = \mathcal{T}[x_1(n)] + \mathcal{T}[x_2(n)]\)

Time or Shift Invariant

A discrete-time systems is shift invariant if and only if

\(y(n) = \mathcal{T}[x(n)] \Rightarrow y(n - k) = \mathcal{T}[x(n - k)]\)

If the input to a system is delayed by k, the output should be the same output delayed by k.

Causality

A discrete-time system is causal if the output at any index n depends only the current and previous indices

\(y(n) = \mathcal{T}[x(n), x(n-1), x(n-2), ...]\)

A system that is a function of future values of the input in addition to the current and previous inputs is noncausal. A systems that is a function of only future inputs is anti-causal.

Stability

A discrete-time system is bounded input-bounded output (BIBO) stable if every bounded input produces a bounded output.

If \( |x(n)| \leq K < \infty \Rightarrow |y(n)| \leq M < \infty \;\; \forall n \) then the system is BIBO stable.

Static vs Dynamic

A discrete-time system that is only dependent on the input at current index is static or a memoryless system. Systems that depend on previous or future values of the input are dynamic systems.