The CPU can only directly fetch instructions and data

from cache memory, located directly on the processor chip.

Cache memory must be loaded in from the main system memory

(the Random Access Memory, or RAM). RAM however, only retains

its contents when the power is on, so needs to be stored on

more permanent storage.

We call these layers of memory the memory

hierarchy

Table 3.1. Memory Hierarchy

| Speed | Memory | Description |

|---|

| Fastest | Cache | Cache memory is memory actually embedded inside

the CPU. Cache memory is very fast, typically taking

only once cycle to access, but since it is embedded

directly into the CPU there is a limit to how big it

can be. In fact, there are several sub-levels of

cache memory (termed L1, L2, L3) all with slightly

increasing speeds. |

| | RAM | All instructions and storage addresses for the

processor must come from RAM. Although RAM is very

fast, there is still some significant time taken for

the CPU to access it (this is termed

latency). RAM is stored in

separate, dedicated chips attached to the motherboard,

meaning it is much larger than cache memory.

|

| Slowest | Disk | We are all familiar with software arriving on a

floppy disk or CDROM, and saving our files to the hard

disk. We are also familiar with the long time a

program can take to load from the hard disk -- having

physical mechanisms such as spinning disks and moving

heads means disks are the slowest form of storage.

But they are also by far the largest form of

storage. |

The important point to know about the memory hierarchy is

the trade offs between speed and size — the faster the

memory the smaller it is. Of course, if you can find a way to

change this equation, you'll end up a billionaire!

The reason caches are effective is because computer code

generally exhibits two forms of locality

Spatial locality suggests that

data within blocks is likely to be accessed together.

Temporal locality suggests that

data that was used recently will likely be used again

shortly.

This means that benefits are gained by implementing as much

quickly accessible memory (temporal) storing small blocks of

relevant information (spatial) as practically possible.

Cache is one of the most important elements of the CPU

architecture. To write efficient code developers need to

have an understanding of how the cache in their systems

works.

The cache is a very fast copy of the slower main system

memory. Cache is much smaller than main memories because it is

included inside the processor chip alongside the registers and

processor logic. This is prime real estate in computing terms,

and there are both economic and physical limits to its maximum

size. As manufacturers find more and more ways to cram more and

more transistors onto a chip cache sizes grow considerably, but

even the largest caches are tens of megabytes, rather than the

gigabytes of main memory or terabytes of hard disk otherwise

common.

The cache is made up of small chunks of mirrored main

memory. The size of these chunks is called the line

size, and is typically something like 32 or 64

bytes. When talking about cache, it is very common to talk

about the line size, or a cache line, which refers to one

chunk of mirrored main memory. The cache can only load and

store memory in sizes a multiple of a cache line.

Caches have their own hierarchy, commonly termed L1, L2

and L3. L1 cache is the fastest and smallest; L2 is bigger

and slower, and L3 more so.

L1 caches are generally further split into instruction

caches and data, known as the "Harvard Architecture" after

the relay based Harvard Mark-1 computer which introduced it.

Split caches help to reduce pipeline bottlenecks as earlier

pipeline stages tend to reference the instruction cache and

later stages the data cache. Apart from reducing contention

for a shared resource, providing separate caches for

instructions also allows for alternate implementations which

may take advantage of the nature of instruction streaming;

they are read-only so do not need expensive on-chip features

such as multi-porting, nor need to handle handle sub-block

reads because the instruction stream generally uses more

regular sized accesses.

During normal operation the processor is constantly

asking the cache to check if a particular address is

stored in the cache, so the cache needs some way to very

quickly find if it has a valid line present or not. If a

given address can be cached anywhere within the cache,

every cache line needs to be searched every time a

reference is made to determine a hit or a miss. To keep

searching fast this is done in parallel in the cache

hardware, but searching every entry is generally far too

expensive to implement for a reasonable sized cache.

Thus the cache can be made simpler by enforcing limits

on where a particular address must live. This is a

trade-off; the cache is obviously much, much smaller

than the system memory, so some addresses must

alias others. If two addresses

which alias each other are being constantly updated they

are said to fight over the cache

line. Thus we can categorise caches into three general

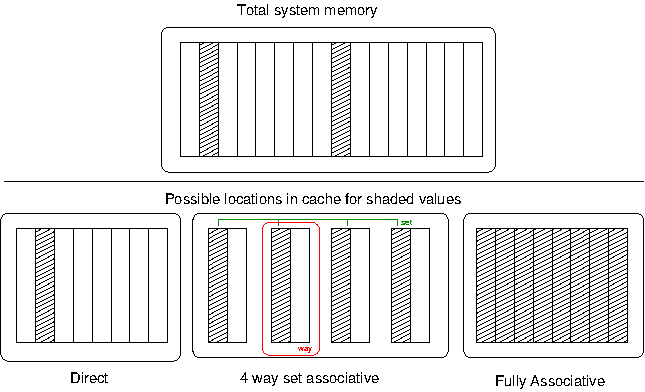

types, illustrated in Figure 3.4, “Cache Associativity”.

Direct mapped caches will allow a

cache line to exist only in a singe entry in the

cache. This is the simplest to implement in hardware,

but as illustrated in Figure 3.4, “Cache Associativity” there is no

potential to avoid aliasing because the two shaded

addresses must share the same cache line.

Fully Associative caches will allow

a cache line to exist in any entry of the cache. This

avoids the problem with aliasing, since any entry is

available for use. But it is very expensive to implement

in hardware because every possible location must be

looked up simultaneously to determine if a value is in

the cache.

Set Associative caches are a hybrid

of direct and fully associative caches, and allow a

particular cache value to exist in some subset of the

lines within the cache. The cache is divided into even

compartments called ways, and a

particular address could be located in any way. Thus an

n-way set associative cache will

allow a cache line to exist in any entry of a set sized

total blocks mod n — Figure 3.4, “Cache Associativity” shows a sample

8-element, 4-way set associative cache; in this case the

two addresses have four possible locations, meaning only

half the cache must be searched upon lookup. The more

ways, the more possible locations and the less aliasing,

leading to overall better performance.

Once the cache is full the processor needs to get rid of

a line to make room for a new line. There are many algorithms

by which the processor can choose which line to evict; for

example least recently used (LRU) is an

algorithm where the oldest unused line is discarded to make

room for the new line.

When data is only read from the cache there is no need

to ensure consistency with main memory. However, when the

processor starts writing to cache lines it needs to make some

decisions about how to update the underlying main memory. A

write-through cache will write the

changes directly into the main system memory as the processor

updates the cache. This is slower since the process of

writing to the main memory is, as we have seen, slower.

Alternatively a write-back cache delays

writing the changes to RAM until absolutely necessary. The

obvious advantage is that less main memory access is

required when cache entries are written. Cache lines that

have been written but not committed to memory are referred to

as dirty. The disadvantage is that when

a cache entry is evicted, it may require two memory accesses

(one to write dirty data main memory, and another to load the

new data).

If an entry exists in both a higher-level and lower-level

cache at the same time, we say the higher-level cache is

inclusive. Alternatively, if the

higher-level cache having a line removes the possibility of a

lower level cache having that line, we say it is

exclusive. This choice is discussed

further in the section called “Cache exclusivity in SMP systems”.

So far we have not discussed how a cache decides if a

given address resides in the cache or not. Clearly, caches

must keep a directory of what data currently resides in the

cache lines. The cache directory and data may co-located on

the processor, but may also be separate — such as in

the case of the POWER5 processor which has an on-core L3

directory, but actually accessing the data requires

traversing the L3 bus to access off-core memory. An

arrangement like this can facilitate quicker hit/miss

processing without the other costs of keeping the entire

cache on-core.

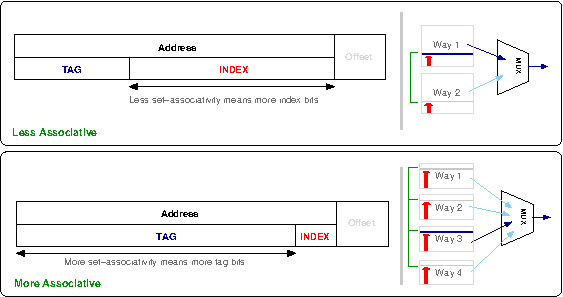

To quickly decide if an address lies within the cache it

is separated into three parts; the tag

and the index and the

offset.

The offset bits depend on the line size of the cache.

For example, a 32-byte line size would use the last 5-bits

(i.e. 25) of the address as the

offset into the line.

The index is the particular cache

line that an entry may reside in. As an example, let us

consider a cache with 256 entries. If this is a direct-mapped

cache, we know the data may reside in only one possible line,

so the next 8-bits (28) after the

offset describe the line to check - between 0 and 255.

Now, consider the same 256 element cache, but divided

into two ways. This means there are two groups of 128 lines,

and the given address may reside in either of these groups.

Consequently only 7-bits are required as an index to offset

into the 128-entry ways. For a given cache size, as we

increase the number of ways, we decrease the number of bits

required as an index since each way gets smaller.

The cache directory still needs to check if the

particular address stored in the cache is the one it is

interested in. Thus the remaining bits of the address are the

tag bits which the cache directory checks

against the incoming address tag bits to determine if there is

a cache hit or not. This relationship is illustrated in Figure 3.5, “Cache tags”.

When there are multiple ways, this check must happen in

parallel within each way, which then passes its result into a

multiplexor which outputs a final hit or

miss result. As describe above, the more

associative a cache is, the less bits are required for index

and the more as tag bits — to the extreme of a

fully-associative cache where no bits are used as index bits.

The parallel matching of tags bits is the expensive component

of cache design and generally the limiting factor on how many

lines (i.e, how big) a cache may grow.