In this project, we are using the Google geocoding API to clean up some user-entered geographic locations of university names and then placing the data on a Google map.

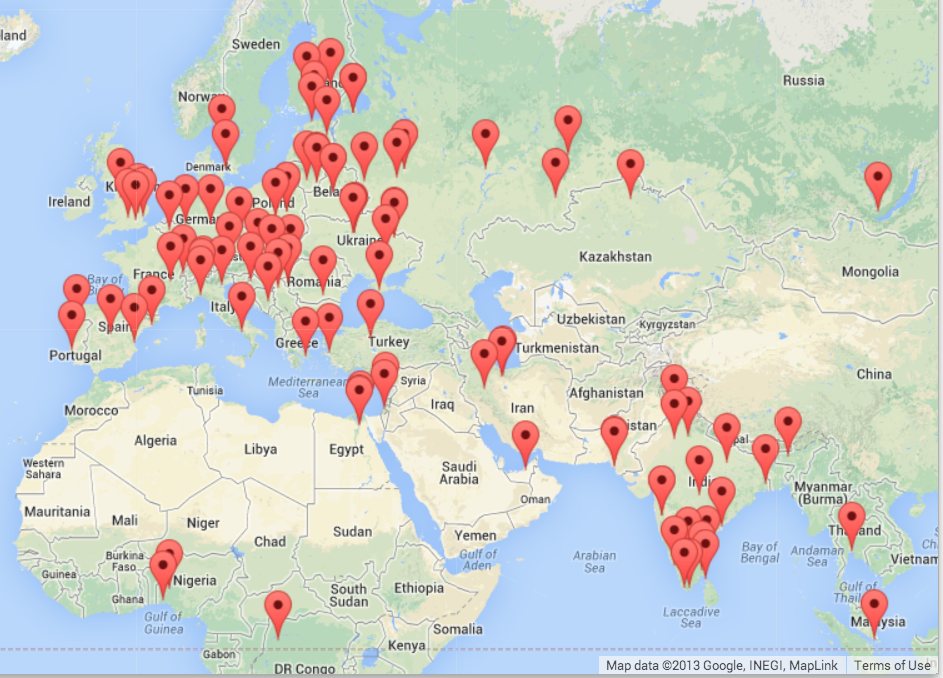

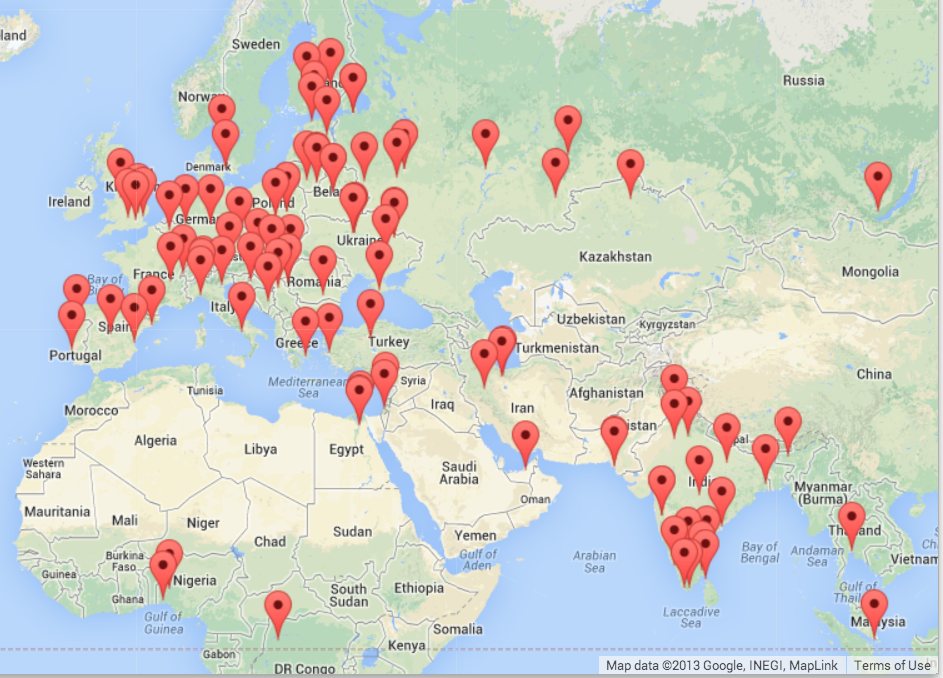

A Google Map

To get started, download the application from:

www.py4e.com/code3/geodata.zip

The first problem to solve is that the free Google geocoding API is rate-limited to a certain number of requests per day. If you have a lot of data, you might need to stop and restart the lookup process several times. So we break the problem into two phases.

In the first phase we take our input "survey" data in the file where.data and read it one line at a time, and retrieve the geocoded information from Google and store it in a database geodata.sqlite. Before we use the geocoding API for each user-entered location, we simply check to see if we already have the data for that particular line of input. The database is functioning as a local "cache" of our geocoding data to make sure we never ask Google for the same data twice.

You can restart the process at any time by removing the file geodata.sqlite.

Run the geoload.py program. This program will read the input lines in where.data and for each line check to see if it is already in the database. If we don't have the data for the location, it will call the geocoding API to retrieve the data and store it in the database.

Here is a sample run after there is already some data in the database:

Found in database Northeastern University

Found in database University of Hong Kong, ...

Found in database Technion

Found in database Viswakarma Institute, Pune, India

Found in database UMD

Found in database Tufts University

Resolving Monash University

Retrieving http://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/

geocode/json?address=Monash+University

Retrieved 2063 characters { "results" : [

{'status': 'OK', 'results': ... }

Resolving Kokshetau Institute of Economics and Management

Retrieving http://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/

geocode/json?address=Kokshetau+Inst ...

Retrieved 1749 characters { "results" : [

{'status': 'OK', 'results': ... }

...

The first five locations are already in the database and so they are skipped. The program scans to the point where it finds new locations and starts retrieving them.

The geoload.py program can be stopped at any time, and there is a counter that you can use to limit the number of calls to the geocoding API for each run. Given that the where.dataonly has a few hundred data items, you should not run into the daily rate limit, but if you had more data it might take several runs over several days to get your database to have all of the geocoded data for your input.

Once you have some data loaded into geodata.sqlite, you can visualize the data using the geodump.py program. This program reads the database and writes the file where.js with the location, latitude, and longitude in the form of executable JavaScript code.

A run of the geodump.py program is as follows:

Northeastern University, ... Boston, MA 02115, USA 42.3396998 -71.08975

Bradley University, 1501 ... Peoria, IL 61625, USA 40.6963857 -89.6160811

...

Technion, Viazman 87, Kesalsaba, 32000, Israel 32.7775 35.0216667

Monash University Clayton ... VIC 3800, Australia -37.9152113 145.134682

Kokshetau, Kazakhstan 53.2833333 69.3833333

...

12 records written to where.js

Open where.html to view the data in a browser

The file where.html consists of HTML and JavaScript to visualize a Google map. It reads the most recent data in where.js to get the data to be visualized. Here is the format of the where.js file:

myData = [

[42.3396998,-71.08975, 'Northeastern Uni ... Boston, MA 02115'],

[40.6963857,-89.6160811, 'Bradley University, ... Peoria, IL 61625, USA'],

[32.7775,35.0216667, 'Technion, Viazman 87, Kesalsaba, 32000, Israel'],

...

];

This is a JavaScript variable that contains a list of lists. The syntax for JavaScript list constants is very similar to Python, so the syntax should be familiar to you.

Simply open where.html in a browser to see the locations. You can hover over each map pin to find the location that the geocoding API returned for the user-entered input. If you cannot see any data when you open the where.html file, you might want to check the JavaScript or developer console for your browser.