11.1: Gimp - A 2D Painting Program

- Page ID

- 14095

Gimp, the Gnu Image Manipulation Program, is a free and open-source program that has many of the capabilities of the better-known commercial program, Adobe Photoshop. Gimp can be used both for creating images from scratch and for modifying existing images. This book covers only a very limited subset of Gimp’s features. It’s easy to find documentation and tutorials on Gimp, starting with its “Help” menu.

Gimp can be downloaded from http://www.gimp.org. It is available for Linux, Mac OS, and Windows. This appendix is based on Gimp 2.8, which is the latest stable version as of January, 2018. The user manual is available on-line at http://docs.gimp.org/2.8/en.

Note that when you start Gimp 2.8 for the first time, it will be in “multi-window mode.” I find it much easier to use “single-window mode,” which organizes all of Gimp’s open images and dialogs into one window. To use it, just enable the option “Single-Window Mode” in the “Windows” menu. You will then see a window with a central area where you can work on images, with dialogs along the left and right edges. The central editing area uses tabs when multiple images are open. There are also tabs on the dialog window to the right that allow you to access several different dialogs.

If you ever mess up the original window layout, it can be difficult to figure out how to get it back. To do that: Select the “Preferences” command from the menu. Go to the “Window Management” section of the preferences. Click “Reset Saved Window Positions to Default Values.” Restart Gimp for the changes to take effect. And finally, switch back to single-window mode by selecting the option in the “Windows” menu.

Gimp’s “File” menu has a “New” command that lets you create a new image from scratch. You will be able to set the size of the image and other properties, such as background color. And there is an “Open” command that lets you open an existing image for editing.

Saving is a little more problematic. The “Save” command will save an “.xcf” file, which is Gimp’s own format. An xcf file is not an image, and it can only be opened with Gimp. It saves the full Gimp editing environment, which you need for more complex projects if you want to be able to return to editing them later.

To save an image file, you should use the “Export” or “Export As” command in the “File” menu. If you opened an image file for editing, the “Export” command becomes an “Overwrite” command that is used to replace the original image with the edited version. These commands let you save images in a wide variety of formats. In general, you should save your images in JPEG or PNG format.

Painting Tools

I strongly suggest that you get Gimp and experiment with it as you read about it here! As you experiment, remember that you can always use Control-Z to undo any action.

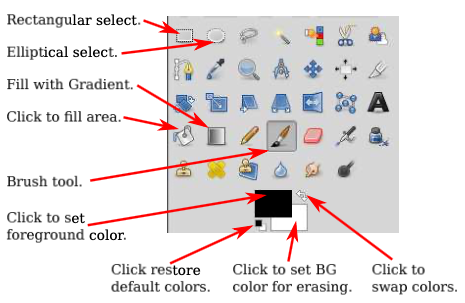

Gimp has a wide variety of tools, which you can find in the “Toolbox” in the upper left corner of the window. (My discussion here assumes that you are working in single-window mode, with the window in its original configuration.) You can hover your mouse over a tool button to find out what the tool is for. Click a button to select a tool. Click or drag the mouse on an image window to apply the selected tool. The Toolbox also has buttons for controlling the foreground and background color. Here is an illustration of the Toolbox with a few annotations:

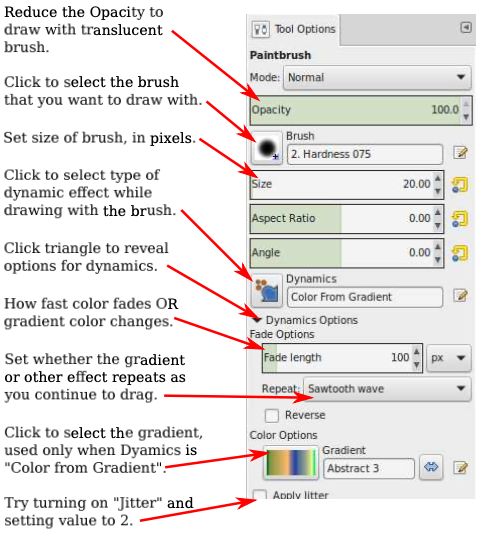

Below the Toolbox is the “Tool Options” dialog, which contains options for the drawing tool that is currently selected. The contents of the dialog change when you select a new tool. Here, for example, are the options for the Brush tool, which is used for painting on an image in the usual sense. The Brush is probably the most basic and useful tool:

You’ll notice that Gimp does not have tools for drawing shapes such as rectangles and circles. However, it is possible to draw such shapes using selections. The selection tools—at the top of the Toolbox—can be used to select regions in the image. For example, click the Rectangle tool, and drag the mouse on the image to select a rectangular region. One of the settings in the “Tool Options” dialog for the Rectangle Select tool allows you to round off the corners of the rectangle. The Ellipse Select tool can be used to select oval-shaped regions. The Free Select (or Lasso) tool, which is next to the Ellipse, can be used to select polygonal regions: Just click a sequence of points to select the vertices of the polygon, and click back on the initial point to close the polygon. You can also drag the Lasso tool to draw the outline of a region freehand. Once you have a selection, there are many things that you can do with it.

One important fact is that when there is a selection, you can only draw inside the selection— the area outside the selection is completely unaffected by painting tools, or by anything else that you try to do the image! If you forget about this, you can be very confused when you try to apply a painting tool outside the selection and it has no effect at all.

The Bucket Fill Tool, which looks like a spilling paint bucket, is especially useful with selections. After selecting the bucket tool, set the “Affected Area” in its Tool Options dialog to “Fill whole selection”. With that setting, clicking inside the selected area will fill that area with color. Another useful option is the “Fill Type” which allows you to fill regions with either the foreground color, the background color, or a a pattern. To change the pattern that is used, click on the image of the pattern, just below the “Pattern fill” option.

Drawing straight lines in Gimp is a little strange. To draw a line, click the image and immediately release the mouse button. Then press the shift key. Move the mouse while holding down the shift key (without holding down any button on the mouse). Then click the mouse again. A line is drawn from the original click to the final click. You can apply this technique to the Brush tool as well as to other tools, such as the Eraser.

The Gradient tool allows you to paint with gradients. A gradient is a smoothly-changing sequence of colors, arranged in some pattern. Many different gradients are available in Gimp. After selecting the Gradient tool, click the image of the gradient in the Tool Options dialog to select the gradient that you would like to use. Note that some of the more interesting gradients include transparent colors, which create regions where the gradient is transparent or translucent.

Linear gradients, radial gradients and other shapes can be selected using the “Shape” setting in the gradient Tool Options. And you can get much smoother-looking gradients by turning on the “Adaptive supersampling” option.

To apply a gradient to an image, press the left mouse button at the point where you want the color sequence to start, drag the mouse while holding down the button, and release the button at the point where you want the color sequence to end. Remember that you can limit the area affected by the gradient by making a selection; that is, you can fill a shape with a gradient by creating the shape as a selection and then applying the gradient tool. Here is an image that was created entirely with a few applications of the gradient tool:

For this picture, the background was made by selecting the gradient named “Land and Sea”, setting the gradient Shape set to “Linear”, and dragging the mouse from the bottom of the image to the top. The frame around the edges was made using the “Square Wood Frame” gradient with the Shape option set to “Square”. Much of the “Square Wood Frame” gradient is transparent. The frame was made by dragging the mouse from the center of the image to the edge, but the only opaque part of the gradient was near the edges. The eye was made using a “Radial Eyeball” gradient with the shape set to “Radial”. And the rainbow used the “Radial Rainbow Hoop” gradient with the shape set to “Radial.” A rectangular selection was used while creating the rainbow. Without the selection, the rainbow would have been a full circle. However, only part of that circle was inside the selection, so only that part was drawn.

You will want to try some of the other tools as well, such as the Smudge tool, the Eraser, and the Clone tool. For help on using any tool, look at the message in the bottom of the image window while using the tool. Consult the user manual if you want to learn more.

In addition to its painting tools, Gimp has a wide variety of color manipulation tools that apply to an entire image at once. Look for them in the “Color” menu and in the “Filter” menu. These tools are often used to modify the colors in photographs or to apply effects to images.

For example, the “Brightness and Contrast” command in the “Color” menu opens a dialog that can be used to adjust the brightness and the contrast of an image, while the “Color Balance” and “Hue-Saturation” dialogs in the same menu can be used to adjust the color. Remember that if there is a selection, then the change will apply only to the pixels in the selected area.

As an example, I used the “Hue-Saturation” dialog to change the color of the flowers in an image from purple to pink:

(The original image, on the left, is from Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org, which is a good source of images for experimentation. This image is in the public domain.) Note that only the colors of the flowers have been modified, not the leaves or branches. To make that possible, I had to select the flowers before changing the color, so that the color change would be limited to the selection. The selection was made using the “Select by Color” tool. If you click on an image using that tool, all pixels that have a similar color to the clicked pixel will be selected. By holding down the shift key as you click, you can add new pixels to the pixels that were already selected. I found that it was easier to get the selection that I wanted when I change the “Threshold” option for the tool from 15.0 to 30.0; this option determines how similar the colors have to be. I had to click many times, using Control-Z whenever I accidently added too much to the selection. Once the selection was ready, I selected “Hue-Saturation” from the “Color” menu, changed the hue, and increased both the lightness and the saturation to get the color that I wanted.

Another way to modify an image is with a filter. Filters in Gimp can be very general. They might better be called “effects.” For example, there is a filter for blurring the image, one for making the image look like an old photograph, and one to make it look like it’s made out of cloth. Some filters in Gimp generate images from nothing, and some do even more complicated things. You will find Gimp’s filters in the “Filter” menu. I will not discuss them further here, but some interesting filters to try include: Distorts/Emboss, Distorts/Mosaic, Distorts/Ripple, Edge-Detect, Artistic/Apply-Canvas, Artistic/Cubism, Decor/Old-Photo, and Map/Warp.

Selections and Paths

Selections are very important in Gimp, and there is a lot more to learn about them. One of the most important things to understand about them is that a pixel can be “partially selected.” That is, a selection is not necessarily just a collection of pixels; it’s really an assignment of a “degree of selectedness” to each pixel. For example, the Cut command (Control-X) deletes the content of a selection. It sets a fully selected pixel to transparent (if the image has an alpha component) or to the background color (if there is no alpha component). However, a partially selected pixel will only be partially cut. If there is an alpha component, the pixel becomes translucent; if not, the current color of the pixel is blended with the background color. Similarly, when you fill a selection, the current color of a partially selected pixel is blended with the fill color. This is very much like alpha blending, with the degree of selectedness playing the role of the alpha component. (See Subsection 2.1.4 for a discussion of the alpha color component and alpha blending.)

One way to get partially selected pixels is to “feather” a selection. When a selection is feathered by, say, 10 pixels, the sharp boundary around the selection is replaced by a 10-pixel-wide border, with the degree of selectedness decreasing from one to zero across the width of the border. Use the “Feather” command in the “Select” menu to feather the current selection. Alternatively, selection tools, such as the Rectangle Select tool, have a Tool Option that will automatically feather the border of any selection that you create with the tool. As an example, a feathered elliptical selection was used to make the image on the right, starting from the image on the left:

The original image is, again, a public-domain image from Wikimedia Commons. I started with an elliptical selection around the flowers in the original image. In the Tool Options for the Elliptical Selection tool, the “Feather Edges” option was set to 40. I then applied the “Invert” command from the “Select” menu, which inverted the selection so that the outside of the ellipse was selected instead of the inside. Finally, I used “Cut” to delete the selected region, leaving just the flowers, with a 40-pixel border in which the flowers fade into the background. (Note: To add some visual interest to the image, I applied the “Artistic” / “Oilify” filter to the original before doing the selection.)

Gimp users often put a great deal of work into creating a selection. One way to get more control over selections is with the Path tool, which is discussed below. Another is the “Quick Mask,” which gives you complete control of the degree of selectedness of individual pixels. Use the “Toggle Quick Mask” command in the “Select” menu to turn the Quick Mask on and off. When the Quick Mask is on, the current selection is represented as a translucent pink overlay on the image. The degree of transparency of the overlay corresponds to the degree of selectedness of the pixel. The overlay is completely transparent for fully selected pixels. When the Quick Mask is on, all painting tools affect the mask rather than the image. For example, drawing with black will add to the mask (and therefore subtract from the selection), and drawing with white—or erasing—will subtract from the mask (and therefore add to the selection). When editing the Quick Mask, consider using the pencil tool instead of the brush tool. The pencil tool is the same as the brush tool, except that it does not do any transparency or antialiasing.

A “path” in Gimp is a Bezier curve. (See Subsection 2.2.3.) Paths are not visible in the actual image, but you can “stroke” a path to make it visible. Paths are not selections, but they are closely related. You can convert a path into a selection, or a selection into a path.

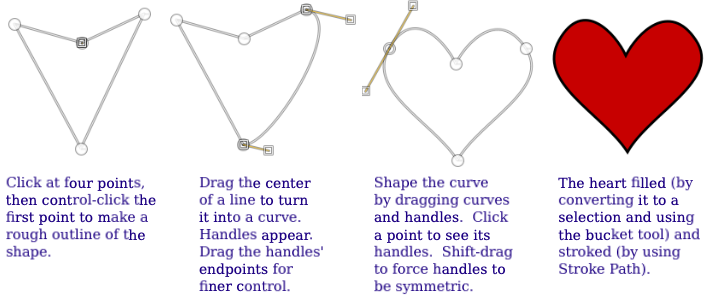

Paths are created using the Path Tool (the eighth tool in the Toolbox). To create a path, click a sequence of points with the Path Tool. Optionally, you can make a closed path by control-clicking back on the first point. This gives a polygonal path. You can then drag on one of the sides of the polygon to change it from a straight line into a curve. When you do that, the usual Bezier control handles will appear at the endpoints of the curve. You can drag the ends of the control handles for finer control of the shape. At a point where two segments of the curve join, there are two control handles. If you hold down the shift key while dragging an end of one of the two handles, then the two handles are constrained to be a straight line and to have the same length, which makes the curve smooth at that point.

Paths are ordinarily not visible except when they are being edited with the Path Tool. However, any path that you create is saved the to Path Dialog. The Path Dialog is one of the four tabbed dialogs in the upper right of the Gimp window. Initially, it is hidden by the Layers Dialog. Click the Paths tab to see the Path Dialog. (See the illustration of the Layers Dialog, later in this section.) The Paths Dialog contains a list of paths. Right-click one of the paths in the list to get a popup menu. From the popup menu, choose “Path Tool” to make the path visible again in the image and to switch to the Path Tool so that the path can be edited. Choose “Path to Selection” from the popup menu to convert the path into a selection; all of the pixels that lie inside the path will be selected. Choose “Stroke Path” to draw a line or drag a paint tool along the path. A dialog box will open to let you set the properties of the stroke. There is also a command “Select to Path” that will convert the current selection into a path; this command is available in the popup menu if you click anywhere in the Path Dialog.

As an example of using paths, this illustration explains how I made a heart shape using the Path Tool:

Layers

In Gimp, an image can be composed from a stack of “layers.” Each layer is itself an image. The final image is composed by starting with a blank canvas, then copying each layer to the canvas, one after the other. A layer doesn’t necessarily have to be the same size as the canvas. A layer be translucent, and can have transparent parts. The advantage of layers is that you can edit one layer without changing the others. You can move a layer (with the Move Tool), and the stuff in the lower layers will be still be there. While layers are used mostly in advanced applications, they are an an important feature and one that can lead to confusion if you don’t know about them—especially since several tools and commands add new layers to an image automatically.

It is important to understand that only one layer can be edited at any given time. That layer is called the active layer. This can be annoying if you lose track of which layer is active. It can be especially annoying if the active layer is hidden in the visible image or has been made completely transparent!

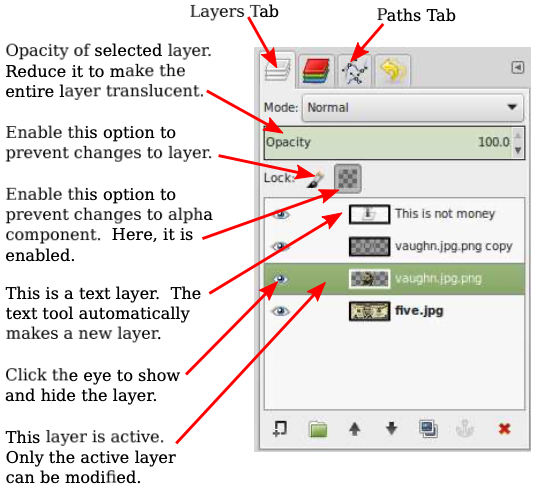

Layers are listed in the Layer Dialog, one of the four tabbed dialogs in the upper right corner of the Gimp window. In the list of layers, the active layer is highlighted. Click a different layer in the list to make it active. Right-click the dialog for a popup menu of commands for working with layers. Some of the commands are duplicated in the “Layer” menu. If you right-click one of the layers in the list, the popup menu will also include commands that apply to that individual layer. Here is an illustration of the Layer Dialog from a project that uses four layers:

A new image will only have one layer. You can add a new layer with a command in the “Layer” menu or in the popup menu that you get by clicking the Layer Dialog. New layers are also added automatically in some cases. The Text Tool, in particular, always creates a new layer. Text layers are special. They only contain text, and they can only be edited with the text tool. (More exactly, if you edit a text layer with some other tool, it is converted into a regular layer, and you can no longer edit it as text.)

The Paste command will also create a new layer. In this case, the layer is special because it is a “floating” layer. After pasting an image into a Gimp window, you can use the Move Tool to drag the floating layer to the desired position. Before you do anything else, aside from moving the layer, you need to either “anchor” the layer (that is, make it part of the active layer), or convert it into a new regular layer. To anchor it, just click outside the pasted layer. To convert it into a regular layer, right click on its entry in the Layer Dialog, and use the “To New Layer” command in the popup menu. (There will also be an “Anchor” command in the menu.) Again, this behavior can be annoying if you don’t know about it.