5.3: Message Composition

- Page ID

- 39593

The three types of messages each have different precedence, which allows them to be composed in an elegant way and with few parentheses.

- Unary messages are always sent first, then binary messages and finally, keyword messages.

- Messages in parentheses are sent prior to any other messages.

- Messages of the same kind are evaluated from left to right.

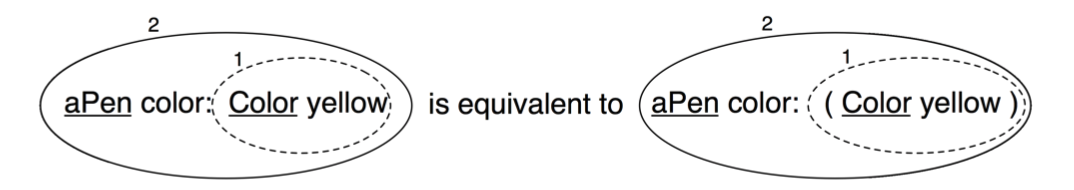

These rules lead to a very natural reading order. If you want to be sure that your messages are sent in the order that you want, you can always add more parentheses, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). In this figure, the message yellow is an unary message and the message color: a keyword message, therefore the message send Color yellow is sent first. However as message sends in parentheses are sent first, putting (unnecessary) parentheses around Color yellow just emphasizes that it will be sent first. The rest of the section illustrates each of these points.

Unary > Binary > Keywords

Unary messages are sent first, then binary messages, and finally keyword messages. We also say that unary messages have a higher priority over the other types of messages.

Important

Rule one. Unary messages are sent first, then binary messages, and finally keyword based messages. Unary > Binary > Keyword.

As these examples show, Pharo’s syntax rules generally ensure that message sends can be read in a natural way:

1000 factorial / 999 factorial >>> 1000

2 raisedTo: 1 + 3 factorial >>> 128

Unfortunately the rules are a bit too simplistic for arithmetic message sends, so you need to introduce parentheses whenever you want to impose a priority over binary operators:

1+2*3 >>> 9

1 + (2 * 3) >>> 7

Example 1. In the message aPen color: Color yellow, there is one unary message yellow sent to the class Color and a keyword message color: sent to aPen. Unary messages are sent first so the message send Color yellow is sent (1). This returns a color object which is passed as argument of the message aPen color: aColor (2) as shown in the following script. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows graphically how messages are sent.

aPen color: Color yellow "unary message is sent first" (1) Color yellow >>> aColor "keyword message is sent next" (2) aPen color: aColor

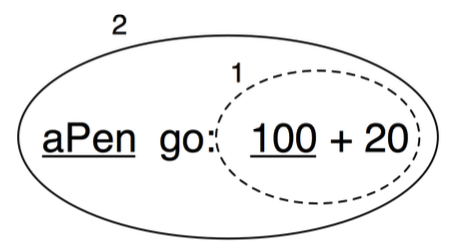

Example 2. In the message aPen go: 100 + 20, there is a binary message + 20 and a keyword message go:. Binary messages are sent prior to keyword messages so 100 + 20 is sent first (1): the message + 20 is sent to the object 100 and returns the number 120. Then the message aPen go: 120 is sent with 120 as argument (2). The following example shows how the message send is executed:

aPen go: 100 + 20 "binary message first" (1) 100 + 20 >>> 120 "then keyword message" (2) aPen go: 120

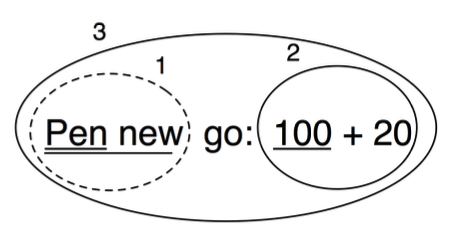

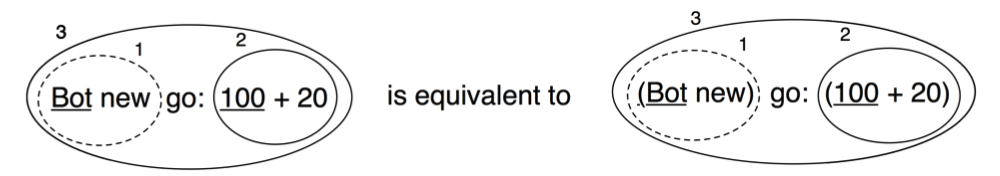

Example 3. As an exercise we let you decompose the evaluation of the message Pen new go: 100 + 20 which is composed of one unary, one keyword and one binary message (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Parentheses first

Parenthesised messages are sent prior to other messages.

3 + 4 factorial >>> 27 "(not 5040)" (3 + 4) factorial >>> 5040

Here we need the parentheses to force sending lowMajorScaleOn: before play.

(FMSound lowMajorScaleOn: FMSound clarinet) play

"(1) send the message clarinet to the FMSound class to create a

clarinet sound.

(2) send this sound to FMSound as argument to the lowMajorScaleOn:

keyword message.

(3) play the resulting sound."

Important

Rule two. Parenthesised messages are sent prior to other messages. (Msg) > Unary > Binary > Keyword

Example 4. The message (65@325 extent: 134@100) center returns the center of a rectangle whose top left point is (65, 325) and whose size is 134x100. The following script shows how the message is decomposed and sent. First the message between parentheses is sent. It contains two binary messages, 65@325 and 134@100, that are sent first and return points, and a keyword message extent: which is then sent and returns a rectangle. Finally the unary message center is sent to the rectangle and a point is returned. Evaluating the message without parentheses would lead to an error because the object 100 does not understand the message center.

(65@325 extent: 134@100) center "Expression within parentheses then binary" (1) 65@325 >>> aPoint "binary" (2)134@100 >>> anotherPoint "keyword" (3) aPoint extent: anotherPoint >>> aRectangle "unary" (4) aRectangle center >>> 132@375

From left to right

Now we know how messages of different kinds or priorities are handled. The final question to be addressed is how messages with the same priority are sent. They are sent from the left to the right. Note that you already saw this behaviour in the previous script where the two point creation messages (@) were sent first.

The following script shows that execution from left to right for messages of the same type reduces the need for parentheses.

1.5 tan rounded asString = (((1.5 tan) rounded) asString) >>> true

Important

Rule three. When the messages are of the same kind, the order of evaluation is from left to right.

Example 5. In the message sends Pen new down all messages are unary messages, so the leftmost one, Pen new, is sent first. This returns a newly created pen to which the second message down is sent, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

Arithmetic inconsistencies

The message composition rules are simple but they result in inconsistency for the execution of arithmetic message sends expressed in terms of binary messages. Here we see the common situations where extra parentheses are needed.

3+4*5 >>> 35 "(not 23) Binary messages sent from left to right"

3 + (4 * 5) >>> 23

1 + 1/3 >>> (2/3) "and not 4/3"

1 + (1/3) >>> (4/3)

1/3 + 2/3 >>> (7/9) "and not 1"

(1/3) + (2/3) >>> 1

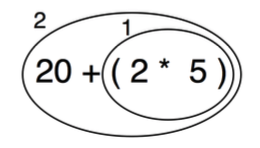

Example 6. In the message sends 20 + 2 * 5, there are only binary messages + and *. However in Pharo there is no special priority for the operations + and *. They are just binary messages, hence * does not have priority over +. Here the leftmost message + is sent first, and then the * is sent to the result as shown in the following script and Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\).

"As there is no priority among binary messages, the leftmost message + is evaluated first even if by the rules of arithmetic the * should be sent first." 20 + 2 * 5 (1) 20 + 2 >>> 22 (2) 22 * 5 >>> 110

As shown in the previous example the result of this message send is not 30 but 110. This result is perhaps unexpected but follows directly from the rules used to send messages. This is the price to pay for the simplicity of the Pharo model. To get the correct result, we should use parentheses. When messages are enclosed in parentheses, they are evaluated first. Hence the message send 20 + (2 * 5) returns the result as shown by the following script and Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\).

"The messages surrounded by parentheses are evaluated first therefore *

is sent prior to + which produces the correct behaviour."

20 + (2 * 5)

(1) (2 * 5)

>>> 10

(2) 20 + 10

>>> 30

Note

Arithmetic operators such as + and * do not have different priority. + and * are just binary messages, therefore * does not have priority over +. Use parentheses to obtain the desired result.

| Implicit precedence | Explicitly parenthesized equivalent |

|---|---|

| aPen color: Color yellow | aPen color: (Color yellow) |

| aPen go: 100 + 20 | Pen go: (100 + 20) |

| aPen penSize: aPen penSize + 2 | aPen penSize: ((aPen penSize) + 2) |

| 2 factorial + 4 | (2 factorial) + 4 |

Note that the first rule stating that unary messages are sent prior to binary and keyword messages avoids the need to put explicit parentheses around them. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) above shows message sends written following the rules and equivalent message sends if the rules would not exist. Both message sends result in the same effect or return the same value.