10.5: Booleans

- Page ID

- 39630

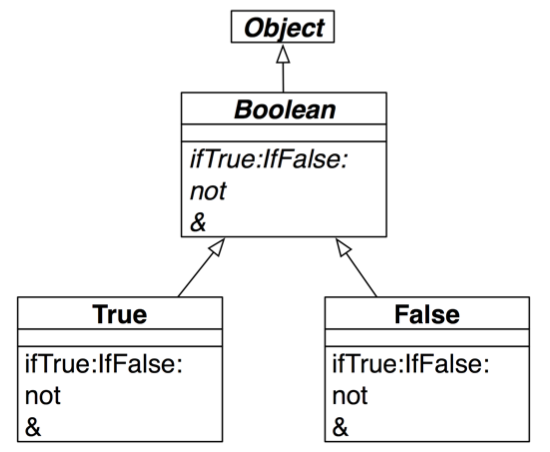

The class Boolean offers a fascinating insight into how much of the Pharo language has been pushed into the class library. Boolean is the abstract superclass of the singleton classes True and False.

Most of the behaviour of Booleans can be understood by considering the method ifTrue:ifFalse:, which takes two Blocks as arguments.

4 factorial > 20

ifTrue: [ 'bigger' ]

ifFalse: [ 'smaller' ]

>>> 'bigger'

The method ifTrue:ifFalse: is abstract in class Boolean. The implementations in its concrete subclasses are both trivial:

True >> ifTrue: trueAlternativeBlock ifFalse: falseAlternativeBlock

^ trueAlternativeBlock value

False >> ifTrue: trueAlternativeBlock ifFalse: falseAlternativeBlock

^ falseAlternativeBlock value

Each of them execute the correct block depending on the receiver of the message. In fact, this is the essence of OOP: when a message is sent to an object, the object itself determines which method will be used to respond. In this case an instance of True simply executes the true alternative, while an instance of False executes the false alternative. All the abstract Boolean methods are implemented in this way for True and False. For example the implementation of negation (message not) is defined the same way:

True >> not

"Negation--answer false since the receiver is true."

^ false

False >> not

"Negation--answer true since the receiver is false."

^ true

Booleans offer several useful convenience methods, such as ifTrue:, ifFalse:, and ifFalse:ifTrue. You also have the choice between eager and lazy conjunctions and disjunctions.

(1>2)&(3<4) >>> false "Eager, must evaluate both sides"

( 1 > 2 ) and: [ 3 < 4 ] >>> false "Lazy, only evaluate receiver"

( 1 > 2 ) and: [ ( 1 / 0 ) > 0 ] >>> false "argument block is never executed, so no exception"

In the first example, both Boolean subexpressions are executed, since & takes a Boolean argument. In the second and third examples, only the first is executed, since and: expects a Block as its argument. The Block is executed only if the first argument is true.

To do. Try to image how

and:andor:are implemented. Check the implementations inBoolean,TrueandFalse.