6.8: Hardware Support

- Page ID

- 77146

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)So far, we have only mentioned that hardware works with the operating system to implement virtual memory. However we have glossed over the details of exactly how this happens.

Virtual memory is necessarily quite dependent on the hardware architecture, and each architecture has its own subtleties. However, there are are a few universal elements to virtual memory in hardware.

All processors have some concept of either operating in physical or virtual mode. In physical mode, the hardware expects that any address will refer to an address in actual system memory. In virtual mode, the hardware knows that addresses will need to be translated to find their physical address.

In many processors, this two modes are simply referred to as physical and virtual mode. Itanium is one such example. The most common processor, the x86, has a lot of baggage from days before virtual memory and so the two modes are referred to as real and protected mode. The first processor to implement protected mode was the 386, and even the most modern processors in the x86 family line can still do real mode, though it is not used. In real mode the processor implements a form of memory organisation called segmentation.

Segmentation is really only interesting as a historical note, since virtual memory has made it less relevant. Segmentation has a number of drawbacks, not the least of which it is very confusing for inexperienced programmers, which virtual memory systems were largely invented to get around.

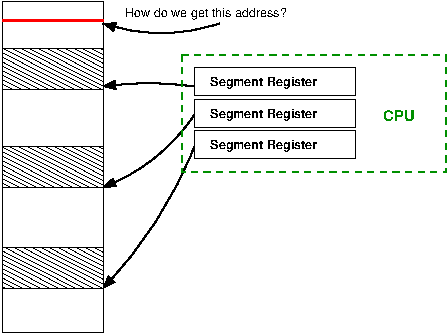

In segmentation there are a number of registers which hold an address that is the start of a segment. The only way to get to an address in memory is to specify it as an offset from one of these segment registers. The size of the segment (and hence the maximum offset you can specify) is determined by the number of bits available to offset from segment base register. In the x86, the maximum offset is 16 bits, or only 64K[18] . This causes all sorts of havoc if one wants to use an address that is more than 64K away, which as memory grew into the megabytes (and now gigabytes) became more than a slight inconvenience to a complete failure.

In the above figure, there are three segment registers which are all pointing to segments. The maximum offset (constrained by the number of bits available) is shown by shading. If the program wants an address outside this range, the segment registers must be reconfigured. This quickly becomes a major annoyance. Virtual memory, on the other hand, allows the program to specify any address and the operating system and hardware do the hard work of translating to a physical address.

The Translation Lookaside Buffer (or TLB for short) is the main component of the processor responsible for virtual-memory. It is a cache of virtual-page to physical-frame translations inside the processor. The operating system and hardware work together to manage the TLB as the system runs.

When a virtual address is requested of the hardware — say via a load instruction requesting to get some data — the processor looks for the virtual-address to physical-address translation in its TLB. If it has a valid translation it can then combine this with the offset portion to go straight to the physical address and complete the load.

However, if the processor can not find a translation in the TLB, the processor must raise a page fault. This is similar to an interrupt (as discussed before) which the operating system must handle.

When the operating system gets a page fault, it needs to go through it's page-table to find the correct translation and insert it into the TLB.

In the case that the operating system can not find a translation in the page table, or alternatively if the operating system checks the permissions of the page in question and the process is not authorised to access it, the operating system must kill the process. If you have ever seen a segmentation fault (or a segfault) this is the operating system killing a process that has overstepped its bounds.

Should the translation be found, and the TLB currently be full, then one translation needs to be removed before another can be inserted. It does not make sense to remove a translation that is likely to be used in the future, as you will incur the cost of finding the entry in the page-tables all over again. TLBs usually use something like a Least Recently Used or LRU algorithm, where the oldest translation that has not been used is ejected in favour of the new one.

The access can then be tried again, and, all going well, should be found in the TLB and translated correctly.

When we say that the operating system finds the translation in the page table, it is logical to ask how the operating system finds the memory that has the page table.

The base of the page table will be kept in a register associated with each process. This is usually called the page-table base-register or similar. By taking the address in this register and adding the page number to it, the correct entry can be located.

There are two other important faults that the TLB can generally generate which help to mange accessed and dirty pages. Each page generally contains an attribute in the form of a single bit which flags if the page has been accessed or is dirty.

An accessed page is simply any page that has been accessed. When a page translation is initially loaded into the TLB the page can be marked as having been accessed (else why were you loading it in?[19])

The operating system can periodically go through all the pages and clear the accessed bit to get an idea of what pages are currently in use. When system memory becomes full and it comes time for the operating system to choose pages to be swapped out to disk, obviously those pages whose accessed bit has not been reset are the best candidates for removal, because they have not been used the longest.

A dirty page is one that has data written to it, and so does not match any data already on disk. For example, if a page is loaded in from swap and then written to by a process, before it can be moved out of swap it needs to have its on disk copy updated. A page that is clean has had no changes, so we do not need the overhead of copying the page back to disk.

Both are similar in that they help the operating system to manage pages. The general concept is that a page has two extra bits; the dirty bit and the accessed bit. When the page is put into the TLB, these bits are set to indicate that the CPU should raise a fault .

When a process tries to reference memory, the hardware does the usual translation process. However, it also does an extra check to see if the accessed flag is not set. If so, it raises a fault to the operating system, which should set the bit and allow the process to continue. Similarly if the hardware detects that it is writing to a page that does not have the dirty bit set, it will raise a fault for the operating system to mark the page as dirty.

We can say that the TLB used by the hardware but managed by software. It is up to the operating system to load the TLB with correct entries and remove old entries.

The process of removing entries from the TLB is called flushing. Updating the TLB is a crucial part of maintaining separate address spaces for processes; since each process can be using the same virtual address not updating the TLB would mean a process might end up overwriting another processes memory (conversely, in the case of threads sharing the address-space is what you want, thus the TLB is not flushed when switching between threads in the same process).

On some processors, every time there is a context switch the entire TLB is flushed. This can be quite expensive, since this means the new process will have to go through the whole process of taking a page fault, finding the page in the page tables and inserting the translation.

Other processors implement an extra address space ID (ASID) which is added to each TLB translation to make it unique. This means each address space (usually each process, but remember threads want to share the same address space) gets its own ID which is stored along with any translations in the TLB. Thus on a context switch the TLB does not need to be flushed, since the next process will have a different address space ID and even if it asks for the same virtual address, the address space ID will differ and so the translation to physical page will be different. This scheme reduces flushing and increases overall system performance, but requires more TLB hardware to hold the ASID bits.

Generally, this is implemented by having an additional register as part of the process state that includes the ASID. When performing a virtual-to-physical translation, the TLB consults this register and will only match those entries that have the same ASID as the currently running process. Of course the width of this register determines the number of ASID's available and thus has performance implications. For an example of ASID's in a processor architecture see the section called “Address spaces”.

While the control of what ends up in the TLB is the domain of the operating system; it is not the whole story. The process described in the section called “Page Faults” describes a page-fault being raised to the operating system, which traverses the page-table to find the virtual-to-physical translation and installs it in the TLB. This would be termed a software-loaded TLB — but there is another alternative; the hardware-loaded TLB.

In a hardware loaded TLB, the processor architecture defines a particular layout of page-table information (the section called “Pages + Frames = Page Tables” which must be followed for virtual address translation to proceed. In response to access to a virtual-address that is not present in the TLB, the processor will automatically walk the page-tables to load the correct translation entry. Only if the translation entry does not exist will the processor raise an exception to be handled by the operating system.

Implementing the page-table traversal in specialised hardware gives speed advantages when finding translations, but removes flexibility from operating-systems implementors who might like to implement alternative schemes for page-tables.

All architectures can be broadly categorised into these two methodologies. Later, we will examine some common architectures and their virtual-memory support.

[18] Imagine that the maximum offset was 32 bits; in this case the entire address space could be accessed as an offset from a segment at 0x00000000 and you would essentially have a flat layout -- but it still isn't as good as virtual memory as you will see. In fact, the only reason it is 16 bits is because the original Intel processors were limited to this, and the chips maintain backwards compatibility.

[19] Actually, if you were loading it in without a pending access this would be called speculation, which is where you do something with the expectation that it will pay off. For example, if code was reading along memory linearly putting the next page translation in the TLB might save time and give a performance improvement.