2.1: Markup Languages

- Page ID

- 3295

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Document markup is a notation method that defines how particular pieces of information are meant to be formatted. The term comes from the practice of marking up manuscripts to notate changes that need to be made. Markup in terms of programming languages is used to identify a language that specifies how a document is to appear.

If you have ever used multiple colors of ink or highlighter when making notes and ascribed meaning to those colors for yourself (e.g., the yellow highlighter is important, red ink is a definition) then you have already practiced document markup. You are providing additional layers of information along with the written text, in this case, visual cues as to the purpose of the written information.

Some popular markup languages are hypertext markup language (HTML), extensible markup language (XML) and extensible hypertext markup language (XHTML). These were each created to fulfill particular needs in defining the layout and structure of the material.

HTML5

Hypertext markup language is used to aid in the publication of web pages by providing a structure that defines elements like tables, forms, lists, and headings, and identifies where different portions of our content begin and end. It can be used to embed other file formats like videos, audio files, documents like PDFs and spreadsheets, among others. HTML is the most relied upon language in the creation of websites. In this text, we will focus on HTML5. While it is technically still in draft form, many proposed elements are already supported by the newer versions of most of the popular browsers.

History

In the beginning, back to the first days of the Internet and ARPA, the primary purpose of creating a page was to share research and information. HTML tags were only meant to provide layout and formatting of a page. As such, early implementations of HTML were somewhat limited as there was little demand for features beyond the basics. Headings, bullets, tables, and color were about all developers had to utilize. As sites were created for other more commercial uses, developers found creative ways of using these tools to get their pages looking more like magazines, advertisements, and what they had drawn on paper. Having been one of those developers, I recall the days of just-get-it-looking-right techniques, splicing page-sized images into tables so graphics were (usually) where we wanted them, nesting tables within tables to create complex layouts and other methods that violate today’s best practices.

Current State

While not formally finalized, many browsers are already supporting a number of features proposed in drafts of HTML5, including things like canvas and media support that greatly improve the browser’s ability to process and display complex materials without requiring extensive coding and extensions. In the past, sites that used video and audio players had to integrate support for many players and would have to include the libraries and formatted files for those systems in their sites. By providing a solution to using these media forms within HTML5, we can improve the user experience and reduce the efforts necessary to provide them.

While these new features to reduce the amount of programming required to implement higher level elements and include interactive elements that exceed document markup activities, HTML5 is still considered a markup language.

In these languages, we use tags to ascribe additional meaning to our text, which provides instruction to the browser as to how to display the text on the screen but are not necessarily displayed to the user. In HTML and XHTML these tags are fixed, or predefined, meaning the names that can be used in the tags are limited to what browsers are able to recognize. In XML, tags are defined by the person creating the content as they are typically used in conjunction with data sources and provide information.

W3C Standards

The World Wide Web Consortium, or W3C, is an international community that supports web development through the creation of open standards that provide the best user experience possible for the widest audience of users. This group of professionals and experts come together to determine how CSS and HTML should operate, what tags should be included as features, and more. The W3C is also your best reference point in determining the accessibility of your site through the use of tools that analyze your code for W3C compliance. These tools confirm if you have fully implemented elements in your code, like providing alternate text descriptions of images in the event that the image cannot load, or the user is visually impaired.

In addition to the creation of accessibility standards, among many others, the W3C also provides tutorials and examples and is likely the most exhaustive reference you will find.

CSS

CSS stands for cascading style sheet and is used to create rules about the color, font, and layout of our pages. It also determines when those rules are to be used, based on information like the device connecting to the page, or in response to a user’s action. CSS can be used by not only HTML but any XML-based language. By separating as much of the look and feel of a page from HTML as possible, we actually separate content from appearance. This makes it possible to quickly create several different versions of the appearance of our site, without recreating the content in each version. Our best approach is to use HTML to define the structure (and only structure) of our pages whenever possible, laying the groundwork for CSS to know where to apply the actual style.

History

As HTML grew in popularity, demands on its feature set also grew. Combined with the variety of browser implementations and their varied approaches to rendering and support, creating robust, visually appealing sites involved a significant amount of time and effort. To reduce these, and separate the duties of presentation from those of content, proposals were sought to define a new system of managing these features. CSS was born out of CHSS, or Cascading Hypertext Style Script, and extends our capabilities by allowing us to go far beyond the styling limits of HTML by giving us more power over images, making pages appear more newspaper or magazine-like with layout and typography effects, and reducing load time.

Introduced for public use in 1996, CSS1 contained the ability to apply rules by identifying elements (selectors), and most of the properties still in use today. CSS2 added the ability to adapt to different displays and devices, as well as positioning elements by specific values on the page. CSS2.1 followed with the introduction of additional features, but these were not considered substantial enough to warrant a full version number change.

Current State

While commonly referred to as CSS3, the numbering no longer applies to the language as a whole. The developers have decided to break the language into modules, allowing different aspects of the language to be revised and released independently of one another. This allows for stable modules to stay numbered as they are (since they are not actually

changing), while those under more active development can be pushed out as needed. At the moment, most of the “current” modules are at version number 3. Some have not really changed from 2.1, while work on version 4 of selected modules is already underway.

Document Object Model

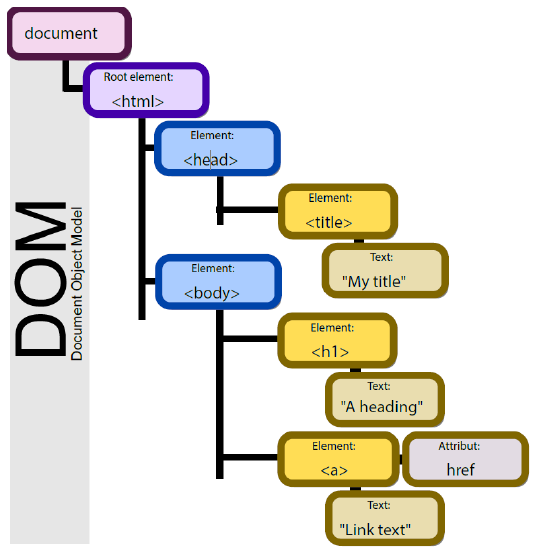

By Birger Eriksson CC-BY-SA-3.0

Figure 20 Document Object Model

Our ability to manipulate and create web pages consistently across formats comes from the document object model API, typically referred to as DOM. This API defines the order and structure of document files as well as how the file is manipulated to create, edit, or remove contents.

The DOM is built to be language and platform independent so any software or programming language can use it to interface with documents. It defines the interface methods and

object types that represent elements of documents, the semantics and behavior of attributes of those objects, and also defines how they relate to one another. The DOM, effectively, is what gives rise to the tags we are about to study below. Languages that use the DOM, however, are not required to include all of its features and may generate additional features of their own.

Figure 20 depicts an example of a document’s model in a tree format, with nested elements appearing to the right and below their parents. In this example, we are shown an HTML page with a section for the head and the body, which includes a page title and a link as its contents. This structure provides the ability for us to traverse, or move around the document, by referring to an object’s name or attribute.