15.1: Fields and Complex Numbers

- Page ID

- 22935

Fields

In order to propely discuss the concept of vector spaces in linear algebra, it is necessary to develop the notion of a set of “scalars” by which we allow a vector to be multiplied. A framework within which our concept of real numbers would fit is desireable. Thus, we would like a set with two associative, commutative operations (like standard addition and multiplication) and a notion of their inverse operations (like subtraction and division). The mathematical algebraic construct that addresses this idea is the field. A field (\(S,+,*\)) is a set \(S\) together with two binary operations \(+\) and \(*\) such that the following properties are satisfied.

- Closure of S under \(+\): For every \(x\), \(y \in S\), \(x+y \in S\).

- Associativity of S under \(+\): For every \(x,y,z \in S\), \((x+y)+z=x+(y+z)\).

- Existence of \(+\) identity element: There is a \(e_+ \in S\) such that for every \(x \in S\), \(e_+ + x = x+e_+=x\).

- Existence of \(+\) inverse elements: For every \(x \in S\) there is a \(y \in S\) such that \(x+y=y+x=e_+\).

- Commutativity of S under \(+\): For every \(x,y \in S\), \(x+y=y+x\).

- Closure of S under \(*\): For every \(x,y \in S\), \(x*y \in S\).

- Associativity of S under \(*\): For every \(x,y,z \in S\), \((x*y)*z=x*(y*z)\).

- Existence of \(*\) identity element: There is a \(e_* \in S\) such that for every \(x \in S\), \(e_*+x=x+e_*=x\).

- Existence of \(*\) inverse elements: For every \(x \in S\) with \(x \neq e_{+}\) there is a \(y \in S\) such that \(x*y=y*x=e_*\).

- Commutativity of S under \(*\): For every \(x,y \in S\), \(x*y=y*x\).

- Distributivity of \(*\) over \(+\): For every \(x,y,z \in S\), \(x*(y+z)=xy+xz\).

While this definition is quite general, the two fields used most often in signal processing, at least within the scope of this course, are the real numbers and the complex numbers, each with their typical addition and multiplication operations.

The Complex Field

The reader is undoubtedly already sufficiently familiar with the real numbers with the typical addition and multiplication operations. However, the field of complex numbers with the typical addition and multiplication operations may be unfamiliar to some. For that reason and its importance to signal processing, it merits a brief explanation here.

Definitions

The notion of the square root of \(-1\) originated with the quadratic formula: the solution of certain quadratic equations mathematically exists only if the so-called imaginary quantity \(\sqrt{-1}\) could be defined. Euler first used \(i\) for the imaginary unit but that notation did not take hold until roughly Ampère's time. Ampère used the symbol \(i\) to denote current (intensité de current). It wasn't until the twentieth century that the importance of complex numbers to circuit theory became evident. By then, using \(i\) for current was entrenched and electrical engineers now choose \(j\) for writing complex numbers.

An imaginary number has the form \(j b=\sqrt{-b^{2}}\). A complex number, \(z\), consists of the ordered pair \((a,b)\), \(a\) is the real component and \(b\) is the imaginary component (the \(j\) is suppressed because the imaginary component of the pair is always in the second position). The imaginary number \(jb\) equals \((0,b)\). Note that \(a\) and \(b\) are real-valued numbers.

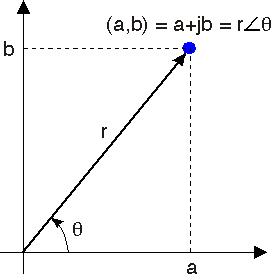

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows that we can locate a complex number in what we call the complex plane. Here, \(a\), the real part, is the \(x\)-coordinate and \(b\), the imaginary part, is the \(y\)-coordinate.

From analytic geometry, we know that locations in the plane can be expressed as the sum of vectors, with the vectors corresponding to the \(x\) and \(y\) directions. Consequently, a complex number \(z\) can be expressed as the (vector) sum \(z=a+jb\) where \(j\) indicates the \(y\)-coordinate. This representation is known as the Cartesian form of \(\mathbf{z}\). An imaginary number can't be numerically added to a real number; rather, this notation for a complex number represents vector addition, but it provides a convenient notation when we perform arithmetic manipulations.

The real part of the complex number \(z=a+jb\), written as \(\operatorname{Re}(z)\), equals \(a\). We consider the real part as a function that works by selecting that component of a complex number not multiplied by \(j\). The imaginary part of \(z\), \(\operatorname{Im}(z)\), equals \(b\): that part of a complex number that is multiplied by \(j\). Again, both the real and imaginary parts of a complex number are real-valued.

The complex conjugate of \(z\), written as \(z^{*}\), has the same real part as \(z\) but an imaginary part of the opposite sign.

\[\begin{align}

z &=\operatorname{Re}(z)+j \operatorname{Im}(z) \nonumber \\

z^{*} &=\operatorname{Re}(z)-j \operatorname{Im}(z)

\end{align} \nonumber \]

Using Cartesian notation, the following properties easily follow.

- If we add two complex numbers, the real part of the result equals the sum of the real parts and the imaginary part equals the sum of the imaginary parts. This property follows from the laws of vector addition.

\[a_{1}+j b_{1}+a_{2}+j b_{2}=a_{1}+a_{2}+j\left(b_{1}+b_{2}\right) \nonumber \]

In this way, the real and imaginary parts remain separate. - The product of \(j\) and a real number is an imaginary number: \(ja\). The product of \(j\) and an imaginary number is a real number: \(j(jb)=−b\) because \(j^2=-1\). Consequently, multiplying a complex number by \(j\) rotates the number's position by \(90\) degrees.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Use the definition of addition to show that the real and imaginary parts can be expressed as a sum/difference of a complex number and its conjugate. \(\operatorname{Re}(z)=\frac{z+z^{*}}{2}\) and \(\operatorname{Im}(z)=\frac{z-z^{*}}{2 j}\)

- Answer

-

\(z+\bar{z}=a+j b+a-j b=2 a=2 \operatorname{Re}(z)\). Similarly, \(z-\bar{z}=a+j b-(a-j b)=2 j b=2(j, \operatorname{Im}(z))\)

Complex numbers can also be expressed in an alternate form, polar form, which we will find quite useful. Polar form arises arises from the geometric interpretation of complex numbers. The Cartesian form of a complex number can be re-written as

\[a+j b=\sqrt{a^{2}+b^{2}}\left(\frac{a}{\sqrt{a^{2}+b^{2}}}+j \frac{b}{\sqrt{a^{2}+b^{2}}}\right) \nonumber \]

By forming a right triangle having sides \(a\) and \(b\), we see that the real and imaginary parts correspond to the cosine and sine of the triangle's base angle. We thus obtain the polar form for complex numbers.

\[\begin{array}{l}

z=a+j b=r \angle \theta \\

r=|z|=\sqrt{a^{2}+b^{2}} \\

a=r \cos (\theta) \\

b=r \sin (\theta) \\

\theta=\arctan \left(\frac{b}{a}\right)

\end{array} \nonumber \]

The quantity \(r\) is known as the magnitude of the complex number \(z\), and is frequently written as \(|z|\). The quantity \(\theta\) is the complex number's angle. In using the arc-tangent formula to find the angle, we must take into account the quadrant in which the complex number lies.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Convert \(3-2j\) to polar form.

- Answer

-

To convert \(3−2j\) to polar form, we first locate the number in the complex plane in the fourth quadrant. The distance from the origin to the complex number is the magnitude \(r\), which equals \(\sqrt{13}=\sqrt{3^{2}+(-2)^{2}}\). The angle equals \(-\arctan \left(\frac{2}{3}\right)\) or \(−0.588\) radians (\(−33.7\) degrees). The final answer is \(\sqrt{13} \angle (-33.7)\) degrees.

Euler's Formula

Surprisingly, the polar form of a complex number \(z\) can be expressed mathematically as

\[z = r ^{j \theta} \nonumber \]

To show this result, we use Euler's relations that express exponentials with imaginary arguments in terms of trigonometric functions.

\[e^{j \theta}=\cos (\theta)+j \sin (\theta) \label{15.3} \]

\[\cos (\theta)=\frac{e^{j \theta}+e^{-(j \theta)}}{2} \label{15.4} \]

\[\sin (\theta)=\frac{e^{j \theta}-e^{-(j \theta)}}{2 j} \nonumber \]

The first of these is easily derived from the Taylor's series for the exponential.

\[e^{x}=1+\frac{x}{1 !}+\frac{x^{2}}{2 !}+\frac{x^{3}}{3 !}+\ldots \nonumber \]

Substituting \(j \theta\) for \(x\), we find that

\[e^{j \theta}=1+j \frac{\theta}{1 !}-\frac{\theta^{2}}{2 !}-j \frac{\theta^{3}}{3 !}+\ldots \nonumber \]

because \(j^2=-1\), \(j^3=-j\), and \(j^4=1\). Grouping separately the real-valued terms and the imaginary-valued ones,

\[e^{j \theta}=1-\frac{\theta^{2}}{2 !}+\cdots+j\left(\frac{\theta}{1 !}-\frac{\theta^{3}}{3 !}+\ldots\right) \nonumber \]

The real-valued terms correspond to the Taylor's series for \(\cos(\theta)\), the imaginary ones to \(\sin(\theta)\), and Euler's first relation results. The remaining relations are easily derived from the first. We see that multiplying the exponential in Equation \ref{15.3} by a real constant corresponds to setting the radius of the complex number by the constant.

Calculating with Complex Numbers

Adding and subtracting complex numbers expressed in Cartesian form is quite easy: You add (subtract) the real parts and imaginary parts separately.

\[z_{1} \pm z_{2}=\left(a_{1} \pm a_{2}\right)+j\left(b_{1} \pm b_{2}\right) \nonumber \]

To multiply two complex numbers in Cartesian form is not quite as easy, but follows directly from following the usual rules of arithmetic.

\[\begin{align}

z_{1} z_{2} &=\left(a_{1}+j b_{1}\right)\left(a_{2}+j b_{2}\right) \nonumber \\

&=a_{1} a_{2}-b_{1} b_{2}+j\left(a_{1} b_{2}+a_{2} b_{1}\right)

\end{align} \nonumber \]

Note that we are, in a sense, multiplying two vectors to obtain another vector. Complex arithmetic provides a unique way of defining vector multiplication.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

What is the product of a complex number and its conjugate?

- Answer

-

\(z \bar{z}=(a+j b)(a-j b)=a^{2}+b^{2}\). Thus \(z \bar{z}=r^{2}=(|z|)^{2}\).

Division requires mathematical manipulation. We convert the division problem into a multiplication problem by multiplying both the numerator and denominator by the conjugate of the denominator.

\[\begin{align}

\frac{z_{1}}{z_{2}} &=\frac{a_{1}+j b_{1}}{a_{2}+j b_{2}} \nonumber \\

&=\frac{a_{1}+j b_{1}}{a_{2}+j b_{2}} \frac{a_{2}-j b_{2}}{a_{2}-j b_{2}} \nonumber \\

&=\frac{\left(a_{1}+j b_{1}\right)\left(a_{2}-j b_{2}\right)}{a_{2}^{2}+b_{2}^{2}} \nonumber \\

&=\frac{a_{1} a_{2}+b_{1} b_{2}+j\left(a_{2} b_{1}-a_{1} b_{2}\right)}{a_{2}^{2}+b_{2}^{2}}

\end{align} \nonumber \]

Because the final result is so complicated, it's best to remember how to perform division—multiplying numerator and denominator by the complex conjugate of the denominator—than trying to remember the final result.

The properties of the exponential make calculating the product and ratio of two complex numbers much simpler when the numbers are expressed in polar form.

\[\begin{align}

z_{1} z_{2} &=r_{1} e^{j \theta_{1}} r_{2} e^{j \theta_{2}} \nonumber \\

&=r_{1} r_{2} e^{j\left(\theta_{1}+\theta_{2}\right)}

\end{align} \nonumber \]

\[\frac{z_{1}}{z_{2}}=\frac{r_{1} e^{j \theta_{2}}}{r_{2} e^{j \theta_{2}}}=\frac{r_{1}}{r_{2}} e^{j\left(\theta_{1}-\theta_{2}\right)} \nonumber \]

To multiply, the radius equals the product of the radii and the angle the sum of the angles. To divide, the radius equals the ratio of the radii and the angle the difference of the angles. When the original complex numbers are in Cartesian form, it's usually worth translating into polar form, then performing the multiplication or division (especially in the case of the latter). Addition and subtraction of polar forms amounts to converting to Cartesian form, performing the arithmetic operation, and converting back to polar form.