1.6: Futures Markets for Crude Oil

- Page ID

- 47688

Future Markets for Crude Oil

Not much has been made here of long-term contracts for oil. This is because up until the early 1980s there were not very many. Production continued as long as the extracted oil could find a home in the spot market. The oil-producing countries, recognizing their market power, either implicitly or explicitly avoided long-term contracts in pursuit of volatile and largely lucrative spot prices.

Following the oil crisis of 1979, the market seemed to have had enough of OPEC's games. Non-OPEC crude production increased as new fields were opened up in Alaska and the U.K., where there was a healthy forward market for Brent crude oil. The New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) officially opened its doors to oil trading in 1983, although the exchange had started selling product futures some years before. Forward markets arose because while the spot market was good for the OPEC governments, it was lousy for oil companies, refiners and other government buyers. Although the number of these buyers was still relatively small, they needed a way to hedge the spot market, and traders were the means to this end.

We have already explained the difference between spot markets and forward markets. Both are "physical" markets, in that their main purpose is to exchange commodities between willing buyers and sellers. A spot or forward transaction typically involves the exchange of money for a physical commodity. Within the past few decades, entities with sufficiently large exposure in the physical market (i.e., the need to buy or sell lots of physical barrels of crude oil) have developed financial instruments that can help them "hedge" or control price volatility. By far the most important of these financial instruments is the "futures" contract.

Futures contracts differ from forward contracts in three important ways. First, futures contracts are highly standardized and non-customizable. The NYMEX futures contract is very tightly defined, in terms of the quantity and quality of oil that makes up a single contract, the delivery location and the prescribed date of delivery. Forward contracts are crafted between a willing buyer and seller and can include whatever terms are mutually agreeable. Second, futures contracts are traded through financial exchanges instead of in one-on-one or "bilateral" transactions. A futures contract for crude oil can be purchased on the NYMEX exchange and nowhere else. Third, futures contracts are typically "financial" in that the contract is settled in cash instead of through delivery of the commodity.

A simple example will illustrate the difference. Suppose I sign a forward contract for crude oil with my neighbor, where she agrees to deliver 100 barrels of crude oil to me in one month, for $50 per barrel. A month from now arrives and my neighbor parks a big truck in my front yard, unloads the barrels, and collects $5000 from me. This is a "physical" transaction. If I were to sign a futures contract with my neighbor, then in one month instead of dropping off 100 barrels of crude oil in front of my house, she pays me the value of that crude oil according to the contract (this is called "settlement" rather than "delivery"). So, I would receive $5000. I could then go and buy 100 barrels of crude oil on the spot market. If the price of crude oil on the spot market was less than $50 per barrel, then in the end I would have made money. If it was more than $50 per barrel, then in the end I would have lost money, but not as much as if I had not signed the futures contract.

This simple example illustrates the primary usefulness of futures contracts, which is hedging against future fluctuations in the spot price. A hedge can be thought of as an insurance policy that partially protects against large swings in the crude oil price.

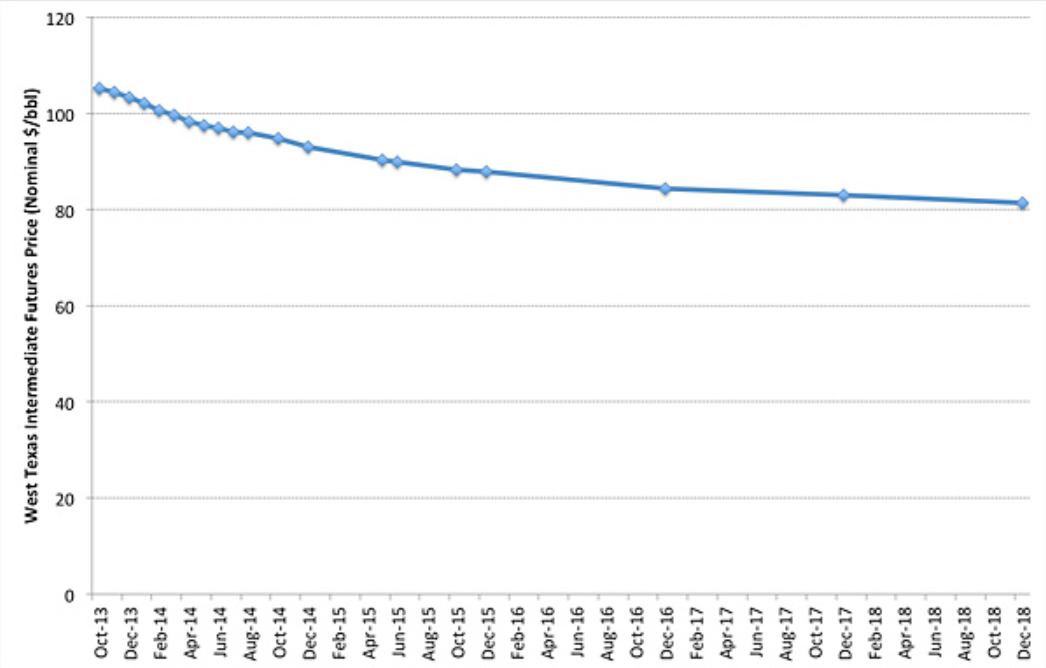

NYMEX (now called the "CME Group") provides a platform for buying and selling crude oil contracts from one month in advance up to eight and a half years forward. The time series of futures prices on a given date is called the "forward curve," and represents the best expectations of the market (on a specific date) as to where the market will go. \(Figure \text { } 1.5\) shows an example of the "forward curve" for crude oil traded on the NYMEX platform. (Note that the data in this figure is dated, and is just for illustration - you'll get your hands dirty with more recent data soon enough.) The value of these expectations, naturally, depends on the number of market participants or "liquidity." For example, on a typical day there are many thousands of crude oil futures contracts traded for delivery or settlement one month in advance. On the other hand, there may be only a few (if any) futures contracts traded for delivery or settlement eight years in advance.

The NYMEX crude oil futures contract involves the buying and selling of oil at a specific location in the North American oil pipeline network. This location, in Cushing Oklahoma, was chosen very specifically because of the amount of oil storage capacity located there and the interconnections to pipelines serving virtually all of the United States. You can read more about the Cushing oil hub in the Lesson 1 Module on Canvas, but it is one of the most important locations in the global energy market.

There is a wealth of data out there on crude oil markets. The following two videos will help orient you towards two websites where you can find information on crude oil prices, demand, shipments and other data. The first covers the NYMEX crude oil futures contract and the second covers the section on crude oil from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Although these are U.S. websites, there is a good amount of data on global markets.

Video: EIA Oil (4:24)

\(Figure \text { } 1.5\): West Texas Intermediate Futures Prices

If you look at \(Figure \text { } 1.5\), you might notice that the price of crude oil generally declines as you move farther out into the future. This is called "backwardation." The opposite, in which the price of crude oil increases as you move farther out into the future, is called "contango." In general, we expect the crude oil market to be in backwardation most of the time; that is, we expect the future price to be lower than the current (spot) price. This can be true even if we expect demand for crude oil to increase in the future. Why would this be the case? If demand is expected to rise in the future, shouldn't that bring the market into contango?

Sometimes this does happen. Most often, the crude oil market is in backwardation because storing crude oil generally involves low costs and has some inherent value. Suppose you had a barrel of crude oil. You could sell it now, or store it to sell later (maybe the price will be higher). The benefit to storing the barrel of oil is the option to sell it at some future date, or keep on holding on to the barrel. This benefit is known as the "convenience yield." Now, suppose that hundreds of thousands of people were storing barrels of oil to sell one year from now. When one year comes, all those barrels of oil will flood the market, lowering the price (a barrel in the future is also worth less than a barrel today; a process called discounting that we will discuss in a later lesson). Thus, because inventories of crude oil are high, the market expects the price to fall in the future.

The ability to store oil implies that future events can impact spot prices. A known future supply disruption (such as the shuttering of an oil refinery for maintenance) will certainly impact the futures price for oil, but should also impact the spot price as inventories are built up or drawn down ahead of the refinery outage.

We'll close this discussion with a very interesting and entertaining thing that happened in the crude oil market in April 2020, when the price of oil on the futures market went negative, trading at -$37.63 per barrel. This means that if you were a potential buyer of crude oil, someone would have paid you $37.63 for every barrel of oil you agreed to buy. I don't know about you, but no one has ever paid me to fill my car's gas tank. It usually works the other way around. What on earth happened here? This short blog post from RBN Energy has a good explanation, and you can also watch RBN Energy's interview with Larry Cramer. The reason for this price craziness has to do a little bit with panic in the oil market because of the coronavirus pandemic and a little bit with how futures markets work. Basically, what happened was that there were a bunch of crude oil traders who had contracts to buy crude oil for delivery in May 2020. Those traders either had to take physical delivery of a bunch of barrels of crude oil in May, or find someone else to assume their contract (this is called "closing one's position" in commodity market parlance). Well, since the pandemic had hit and crude oil demand had collapsed, there was no one in the market who really wanted to buy crude oil off of these traders. And, there was no place for these traders to physically put their crude oil that they were obligated to take in May 2020. So these traders got caught in a market squeeze and had to pay others to close their positions. It's crazy, and hasn't happened in the crude oil market before...but it makes perfect sense when you realize how this market actually works!