5.2: The Streamfunction

- Page ID

- 18064

Many flows are approximately two-dimensional. For example, the thickness of the Earth’s atmosphere relative to the planet is comparable to the skin on an apple. Large-scale atmospheric flows are therefore nearly two-dimensional. When a flow is two-dimensional and also incompressible \( \left( \vec{\nabla}\cdot\vec{u}=0 \right) \), it can represented by means of a streamfunction \(\psi\). Suppose the two dimensions are \(x\) and \(y\), with corresponding velocity components \(u(x, y)\) and \(v(x, y)\). Then \(\psi\) is defined such that

\[u=-\frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial y} ; \quad v=\frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial x} \label{eqn:1} \]

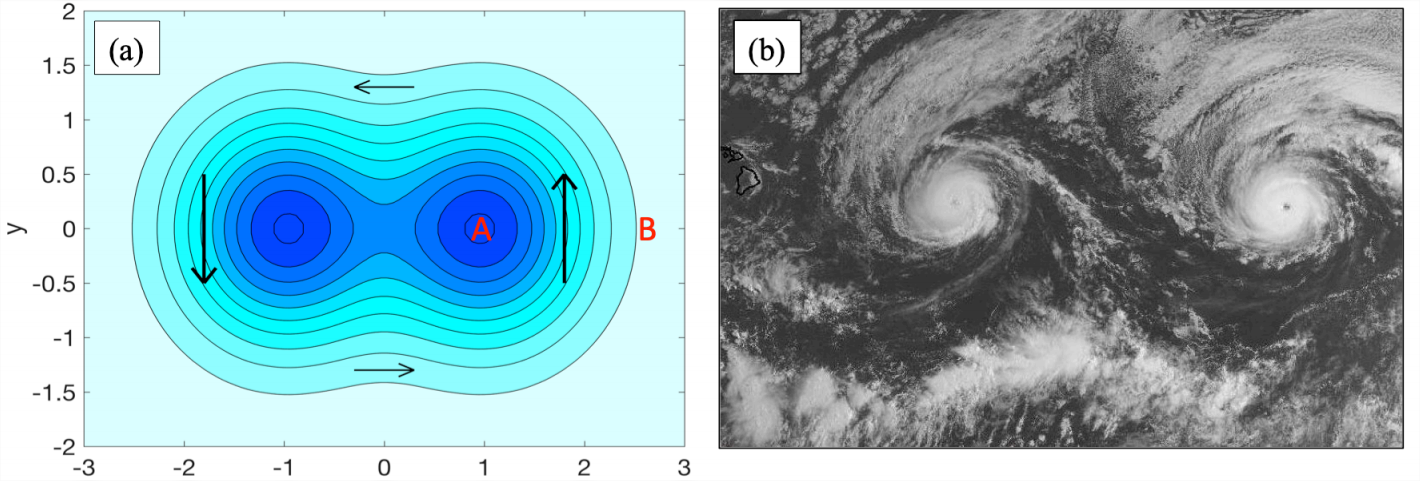

Curves of constant \(\psi\) are called streamlines. The simple example of a pair of nearby minima is shown in (Figure 5.2(a)).

Several properties of the streamfunction are noteworthy.

- The definition Equation \(\ref{eqn:1}\) guarantees that \(\vec{\nabla}\cdot\vec{u}\) will be zero. (Check this for yourself.)

- The sign convention is arbitrary. The present convention leads to \(\omega^{(z)} = +\nabla^2\psi\).

- You can add any fixed number to \(Ψ\) and it makes no difference to the resulting flow. In other words, the streamfunction is defined only up to an additive constant.

- The direction of the flow vector \(\vec{u}\) is perpendicular to \(\vec{\nabla}\psi\) or, equivalently, parallel to the streamlines: \[\vec{u} \cdot \vec{\nabla} \Psi=u \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial x}+v \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial y}=u v-v u=0, \nonumber \] using Equation \(\ref{eqn:1}\).

- The flow direction is defined more fully by noting the signs of the derivatives in Equation \(\ref{eqn:1}\). These require that flow be clockwise around a maximum in \(\psi\) and counterclockwise around a minimum (such as the pair of minima in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). In (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)a), the streamfunction increases (becomes less negative) from point “A” to point “B”, hence \(\partial\psi/\partial x > 0\), hence \(v > 0\).

- The speed (velocity magnitude) is \(\sqrt{u^2+v^2} = |\vec{\nabla}\psi|\). Therefore, the flow is fastest where streamlines are clustered together, such as just outside the two peaks on (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)a). Flow is slow where streamlines are widely spaced.

Given the velocity components \(u\), \(v\), one can easily invert Equation \(\ref{eqn:1}\) to obtain the streamfunction. We can start with either equation; here we’ll pick the first one. Integrating:

\[\Psi=-\int u \, d y+f(x), \nonumber \]

where \(f\) is an unknown function independent of \(y\). Substituting this into the second of Equation \(\ref{eqn:1}\) gives

\[\frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial x}=-\int \frac{\partial u}{\partial x} d y+f^{\prime}(x)=v. \nonumber \]

This is readily solved for \(f^\prime\), which we integrate to obtain \(f\). Note that the constant of integration is arbitrary because of point 3 above.

Test your understanding by doing exercise 23, parts (a) and (b).