3.14: Primitive Drawing Functions

- Page ID

- 14422

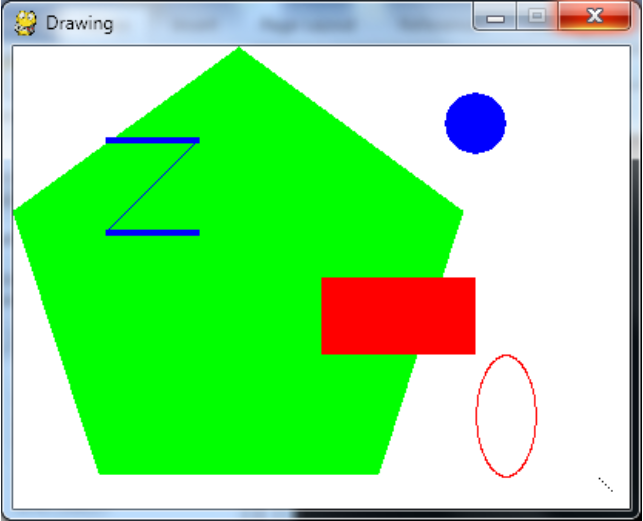

Pygame provides several different functions for drawing different shapes onto a surface object. These shapes such as rectangles, circles, ellipses, lines, or individual pixels are often called drawing primitives. Open IDLE’s file editor and type in the following program, and save it as drawing.py.

import pygame, sys

from pygame.locals import *

pygame.init()

# set up the window

DISPLAYSURF = pygame.display.set_mode((500, 400), 0, 32)

pygame.display.set_caption('Drawing')

# set up the colors

BLACK = (0, 0, 0)

WHITE = (255, 255, 255)

RED = (255, 0, 0)

GREEN = (0, 255, 0)

BLUE = (0, 0, 255)

# draw on the surface object

DISPLAYSURF.fill(WHITE)

pygame.draw.polygon(DISPLAYSURF, GREEN, ((146, 0), (291, 106), (236, 277), (56, 277), (0, 106)))

pygame.draw.line(DISPLAYSURF, BLUE, (60, 60), (120, 60), 4)

pygame.draw.line(DISPLAYSURF, BLUE, (120, 60), (60, 120))

pygame.draw.line(DISPLAYSURF, BLUE, (60, 120), (120, 120), 4)

pygame.draw.circle(DISPLAYSURF, BLUE, (300, 50), 20, 0)

pygame.draw.ellipse(DISPLAYSURF, RED, (300, 250, 40, 80), 1)

pygame.draw.rect(DISPLAYSURF, RED, (200, 150, 100, 50))

pixObj = pygame.PixelArray(DISPLAYSURF)

pixObj[480][380] = BLACK

pixObj[482][382] = BLACK

pixObj[484][384] = BLACK

pixObj[486][386] = BLACK

pixObj[488][388] = BLACK

del pixObj

# run the game loop

while True:

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == QUIT:

pygame.quit()

sys.exit()

pygame.display.update()

When this program is run, the following window is displayed until the user closes the window:

Notice how we make constant variables for each of the colors. Doing this makes our code more readable, because seeing GREEN in the source code is much easier to understand as representing the color green than (0, 255, 0) is.

The drawing functions are named after the shapes they draw. The parameters you pass these functions tell them which Surface object to draw on, where to draw the shape (and what size), in what color, and how wide to make the lines. You can see how these functions are called in the drawing.py program, but here is a short description of each function:

- fill(color) – The

fill()method is not a function but a method ofpygame.Surfaceobjects. It will completely fill in the entire Surface object with whatever color value you pass as thecolorparameter. - pygame.draw.polygon(surface, color, pointlist, width) – A polygon is shape made up of only flat sides. The

surfaceandcolorparameters tell the function on what surface to draw the polygon, and what color to make it.- The

pointlistparameter is a tuple or list of points (that is, tuple or list of two-integer tuples for XY coordinates). The polygon is drawn by drawing lines between each point and the point that comes after it in the tuple. Then a line is drawn from the last point to the first point. You can also pass a list of points instead of a tuple of points. - The

widthparameter is optional. If you leave it out, the polygon that is drawn will be filled in, just like our green polygon on the screen is filled in with color. If you do pass an integer value for thewidthparameter, only the outline of the polygon will be drawn. The integer represents how many pixels width the polygon’s outline will be. Passing1for the width parameter will make a skinny polygon, while passing4or10or20will make thicker polygons. If you pass the integer0for the width parameter, the polygon will be filled in (just like if you left thewidthparameter out entirely). - All of the

pygame.drawdrawing functions have optionalwidthparameters at the end, and they work the same way aspygame.draw.polygon()’swidthparameter. Probably a better name for the width parameter would have beenthickness, since that parameter controls how thick the lines you draw are.

- The

- pygame.draw.line(surface, color, start_point, end_point, width) – This function draws a line between the

start_pointandend_pointparameters. - pygame.draw.lines(surface, color, closed, pointlist, width) – This function draws a series of lines from one point to the next, much like

pygame.draw.polygon(). The only difference is that if you passFalsefor theclosedparameter, there will not be a line from the last point in thepointlistparameter to the first point. If you passTrue, then it will draw a line from the last point to the first. - pygame.draw.circle(surface, color, center_point, radius, width) – This function draws a circle. The center of the circle is at the

center_pointparameter. The integer passed for theradiusparameter sets the size of the circle.- The radius of a circle is the distance from the center to the edge. (The radius of a circle is always half of the diameter.) Passing

20for theradiusparameter will draw a circle that has a radius of 20 pixels.

- The radius of a circle is the distance from the center to the edge. (The radius of a circle is always half of the diameter.) Passing

- pygame.draw.ellipse(surface, color, bounding_rectangle, width) – This function draws an ellipse (which is like a squashed or stretched circle). This function has all the usual parameters, but in order to tell the function how large and where to draw the ellipse, you must specify the bounding rectangle of the ellipse. A bounding rectangle is the smallest rectangle that can be drawn around a shape. Here’s an example of an ellipse and its bounding rectangle:

- The

bounding_rectangleparameter can be apygame.Rectobject or a tuple of four integers. Note that you do not specify the center point for the ellipse like you do for thepygame.draw.circle()function.

- pygame.draw.rect(surface, color, rectangle_tuple, width) – This function draws a rectangle. The

rectangle_tupleis either a tuple of four integers (for the XY coordinates of the top left corner, and the width and height) or apygame.Rectobject can be passed instead. If the rectangle_tuple has the same size for the width and height, a square will be drawn.