13.6: Double Trouble

- Page ID

- 48391

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Sometimes we have to evaluate sums of sums, otherwise known as double summations. This sounds hairy, and sometimes it is. But usually, it is straightforward— you just evaluate the inner sum, replace it with a closed form, and then evaluate the outer sum (which no longer has a summation inside it). For example,5

\[\begin{aligned} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\left( y^n \sum_{i=0}^{n} x^i\right) &= \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \left( y^n \dfrac{1 - x^{n+1}}{1-x} \right) & \text{equation 13.2} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{1-x} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} y^n - \left( \dfrac{1}{1-x} \right)\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} y^n x^{n+1} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{(1-x)(1-y)} - \left( \dfrac{x}{1-x} \right) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (xy)^n & \text{Theorem 13.1.1} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{(1-x)(1-y)} - \dfrac{x}{(1-x)(1-xy)} & \text{Theorem 13.1.1} \\ &= \dfrac{(1-xy)-x(1-y)}{(1-x)(1-y)(1-xy)} \\ &= \dfrac{1-x}{(1-x)(1-y)(1-xy)} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{(1-y)(1-xy)}. \end{aligned}\]

When there’s no obvious closed form for the inner sum, a special trick that is often useful is to try exchanging the order of summation. For example, suppose we want to compute the sum of the first \(n\) harmonic numbers

\[\label{13.6.1} \sum_{k=1}^{n} H_k = \sum_{k=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{k} \dfrac{1}{j}\]

For intuition about this sum, we can apply Theorem 13.3.2 to equation 13.4.3 to conclude that the sum is close to

\[\nonumber \int_{1}^{n} \ln(x) dx = x \ln (x) - x \bigg|_{1}^{n} = n \ln (n) - n + 1.\]

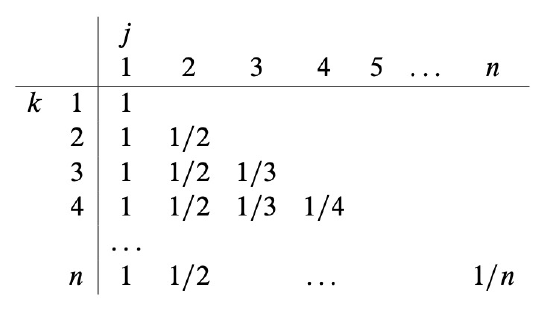

Now let’s look for an exact answer. If we think about the pairs \((k, j)\) over which we are summing, they form a triangle:

The summation in Equation \ref{13.6.1} is summing each row and then adding the row sums. Instead, we can sum the columns and then add the column sums. Inspecting the table we see that this double sum can be written as

\[\begin{align} \nonumber \sum_{k=1}^{n} H_k &= \sum_{k=1}^{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} \dfrac{1}{j} \\ \nonumber &= \sum_{j=1}^{n} \sum_{k=j}^{n} \dfrac{1}{j} \\ \nonumber &= \sum_{j=1}^{n} \dfrac{1}{j} \sum_{k=j}^{n} 1 \\ \nonumber &= \sum_{j=1}^{n} \dfrac{1}{j} (n-j+1) \\ \nonumber &= \sum_{j=1}^{n} \dfrac{n+1}{j} - \sum_{j=1}^{n} \dfrac{j}{j} \\ \nonumber &= (n + 1)\sum_{j=1}^{n} \dfrac{1}{j} - \sum_{j=1}^{n} 1 \\ &= (n+1) H_n - n. \end{align}\]

5OK, so maybe this one is a little hairy, but it is also fairly straightforward. Wait till you see the next one!