15.4: Inner Products

- Page ID

- 22938

Definition: Inner Product

You may have run across inner products, also called dot products, on \(\mathbb{R}^n\) before in some of your math or science courses. If not, we define the inner product as follows, given we have some \(\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{n}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y} \in \mathbb{R}^{n}\).

Definition: Standard Inner Product

The standard inner product is defined mathematically as:

\[\begin{aligned}

\langle\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle &=\boldsymbol{y}^{T} \boldsymbol{x} \\

&=\left(\begin{array}{cccc}

y_{0} & y_{1} & \dots & y_{n-1}

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c}

x_{0} \\

x_{1} \\

\vdots \\

x_{n-1}

\end{array}\right) \\

&=\sum_{i=0}^{n-1} x_{i} y_{i}

\end{aligned} \nonumber \]

Inner Product in 2-D

If we have\(\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathbb{R}^2\) and \(\boldsymbol{y} \in \mathbb{R}^2\), then we can write the inner product as

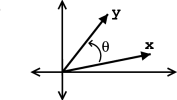

\[\langle\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle=\|\boldsymbol{x}\|\|\boldsymbol{y}\| \cos (\theta) \nonumber \]

where \(\theta\) is the angle between \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\).

Geometrically, the inner product tells us about the strength of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) in the direction of \(\boldsymbol{y}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

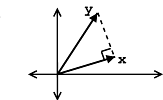

For example, if \(\|x\|=1\), then

\[<x, y>=\|y\| \cos (\theta) \nonumber \]

The following characteristics are revealed by the inner product:

- \(\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle\) measures the length of the projection of \(\boldsymbol{y}\) onto \(\boldsymbol{x}\).

- \(\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle\) is maximum (for given \(\|\boldsymbol{x}\|\), \(\|\boldsymbol{y}\|\)) when \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\) are in the same direction (\((\theta=0) \Rightarrow(\cos (\theta)=1)\)).

- \(\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle\) is zero when \((\cos (\theta)=0) \Rightarrow\left(\theta=90^{\circ}\right)\), i.e. \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\) are orthogonal.

Inner Product Rules

In general, an inner product on a complex vector space is just a function (taking two vectors and returning a complex number) that satisfies certain rules:

- Conjugate Symmetry: \[\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle=\overline{\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle} \nonumber \]

- Scaling: \[\langle\alpha \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y} \rangle=\alpha\langle(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y})\rangle \nonumber \]

- Additivity: \[\langle \boldsymbol{x}+\boldsymbol{y}, \boldsymbol{z} \rangle=\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle+\langle \boldsymbol{y}, \boldsymbol{z}\rangle \nonumber \]

- "Positivity": \[\langle \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{x} \rangle >0, \boldsymbol{x} \neq 0 \nonumber \]

Definition: Orthogonal

We say that \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\) are orthogonal if:

\[\langle\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}\rangle=0 \nonumber \]