4.2: Internal energy in a system

- Page ID

- 88839

The total energy of a system may consist of internal energy, kinetic energy, potential energy, and other forms of energy. For a system free of magnetic, electric, and surface tension effects, its total energy and corresponding specific energy can be expressed as

\[E=U+KE+PE\]

\[e=u+ke+pe\]

where  , and

, and  represent the total energy, internal energy, kinetic energy, and potential energy of a system, respectively;

represent the total energy, internal energy, kinetic energy, and potential energy of a system, respectively;  , and

, and  are their corresponding specific energies. Recall from Chapter 2, internal energy

are their corresponding specific energies. Recall from Chapter 2, internal energy  is a form of thermal energy. A system at different states may have different internal energies due to different temperature and pressure at each state; therefore,

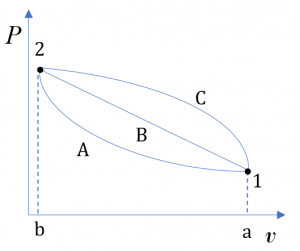

is a form of thermal energy. A system at different states may have different internal energies due to different temperature and pressure at each state; therefore,  is a state function. It is important to note that the change in internal energy in a process depends on the initial and final states, not on the path of the process. For example, although the three processes in Figure 4.1.1 undergo different paths, their changes in internal energy,

is a state function. It is important to note that the change in internal energy in a process depends on the initial and final states, not on the path of the process. For example, although the three processes in Figure 4.1.1 undergo different paths, their changes in internal energy,  , between the two states 1 and 2 are the same because the three processes have identical initial states and identical final states.

, between the two states 1 and 2 are the same because the three processes have identical initial states and identical final states.

The first law of thermodynamics gives the relation between the total energy stored in a system and the energy transferred into or out of the system in the form of heat and work. In this chapter, we will firstly introduce the common methods of determining internal energy and work, and then the first law of thermodynamics and its applications to closed systems.

4.1.1 Using thermodynamic tables to determine specific internal energy u

For pure substances with available thermodynamic tables, the specific internal energy can be read from the thermodynamic tables, then the internal energy can be found from

\[U = mu\]

where

\[m\]

\[U\]

\[u\]

Complete the table, and label each state on the P-T, T-v and P-v diagrams.

| Substance | T

oC |

P

kPa |

v

m3/kg |

u

kJ/kg |

x | Phase | |

| 1 | Water | 60 | 500 | ||||

| 2 | R134a | 40 | 0.1 |

Solution

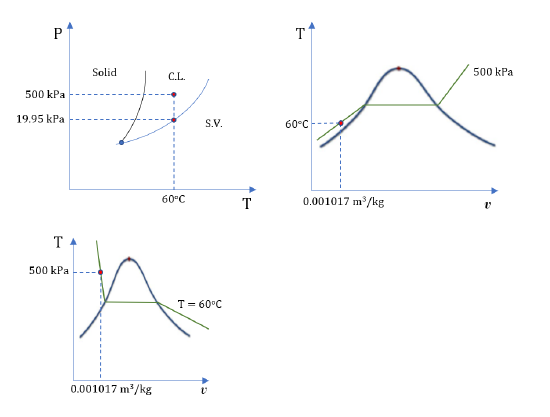

1. Water at 60oC and 500 kPa

From Table A1: Psat = 0.01995 MPa = 19.95 kPa at 60oC. The given pressure P = 500 kPa > Psat ; therefore, water at the given state is a compressed liquid.

From Table A3: v = 0.001017 m3/kg and u = 251.08 kJ/kg for the given state.

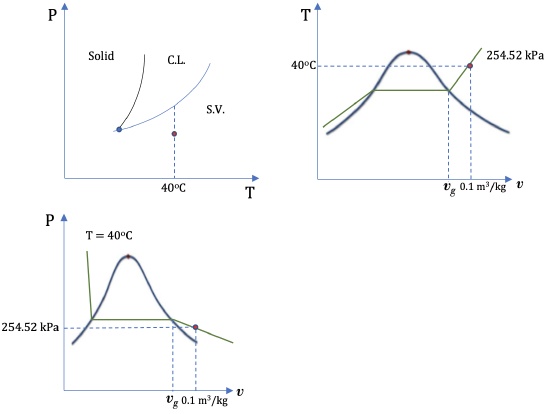

2. R134a at 40oC and 0.1 m3/kg

From Table C1: vg = 0.019966 m3/kg at 40oC. The given specific volume v = 0.1 m3/kg > vg ; therefore, R134a at the given state is a superheated vapour.

From Table C2:

v = 0.080629 m3/kg and u = 410.00 kJ/kg at 40oC and 300 kPa

v = 0.123226 m3/kg and u = 411.22 kJ/kg at 40oC and 200 kPa

Use linear interpolation to find P and u at the given condition

\[\because \dfrac{P-300}{200-300}=\dfrac{0.1-0.080629}{0.123226-0.080629} \\\]

\[\therefore P= 254.52\ \rm{kPa}\\\]

\[\because \dfrac{u-410.00}{411.22-410.00}=\dfrac{0.1-0.080629}{0.123226-0.080629} \\\]

In summary, the table below gives the final answers to the question.

| Substance | T

oC |

P

kPa |

v

m3/kg |

u

kJ/kg |

x | Phase | |

| 1 | Water | 60 | 500 | 0.001017 | 251.08 | n.a. | Compressed liquid |

| 2 | R134a | 40 | 254.52 | 0.1 | 410.55 | n.a. | Superheated vapour |

4.1.2 Constant-volume specific heat

When a substance absorbs heat, its temperature tends to increase. Different substances require different amounts of heat for a given temperature rise. For example, it requires 4.18 kJ of heat to warm up 1 kg of water by 1oC. But it only requires 2.22 kJ of heat to warm up the same amount of gasoline by 1oC. In other words, water and gasoline have different energy storage capacities. Specific heat, also called heat capacity, is an important property used to quantify the energy storage capacity of a substance. Specific heat is defined as the energy required to raise the temperature of one unit mass (i.e., 1 kg) of a substance by one degree (i.e., 1oC, or 1 K),

\[C=\left(\dfrac{1}{m} \dfrac{\delta Q}{\partial T}\right)\]

where

\[C\]

\[m\]

\[\dfrac{\delta Q}{\partial T}\]

The specific heat of a substance may be measured in an isochoric or isobaric process; they are therefore called constant-volume specific heat,  , and constant-pressure specific heat,

, and constant-pressure specific heat,  , respectively. Both

, respectively. Both  and

and  are properties of a substance. They can be used to calculate the changes of specific internal energy,

are properties of a substance. They can be used to calculate the changes of specific internal energy,  , and specific enthalpy,

, and specific enthalpy,  , respectively, in a process involving ideal gases, liquids and solids. The constant-volume specific heat is introduced below in detail and the constant-pressure specific heat will be introduced in Chapter 5.

, respectively, in a process involving ideal gases, liquids and solids. The constant-volume specific heat is introduced below in detail and the constant-pressure specific heat will be introduced in Chapter 5.

Constant-volume specific heat is defined as the energy required to raise the temperature of one unit mass (i.e., 1 kg) of a substance by one degree (i.e., 1oC, or 1 K) in an isochoric process. Mathematically, it is expressed as,

\[C_v=\left(\displaystyle\frac{\partial u}{\partial T}\right)_v\]

where

\[C_v\]

\[u\]

\[T\]

The constant-volume specific heat of selected ideal gases can be found in Appendix G, Table G1. For example, oxygen has  0.658 kJ/kgK. If we heat up 1 kg of oxygen at 300 K in a sealed, rigid tank, it will require 0.658 kJ of heat for the temperature of the oxygen to rise from 300 K to 301 K.

0.658 kJ/kgK. If we heat up 1 kg of oxygen at 300 K in a sealed, rigid tank, it will require 0.658 kJ of heat for the temperature of the oxygen to rise from 300 K to 301 K.

It is important to note that although  is typically measured in isochoric processes, it is a property of a substance. The use of

is typically measured in isochoric processes, it is a property of a substance. The use of  is NOT limited to isochoric processes. As can be seen in the next section, for ideal gases

is NOT limited to isochoric processes. As can be seen in the next section, for ideal gases  can be used to calculate the change in specific internal energy,

can be used to calculate the change in specific internal energy,  , in ANY processes.

, in ANY processes.

4.1.3 Using Cv to calculate Δu for ideal gases

A gas behaves like an ideal gas as its compressibility factor  . The specific internal energy of an ideal gas is a function of temperature only,

. The specific internal energy of an ideal gas is a function of temperature only,  ; therefore,

; therefore,

\[C_v =\left(\dfrac{\partial u}{\partial T}\right)_v=\left(\dfrac{du}{dT}\right)_v= f(T)\]

The change in specific internal energy between two states in any process involving ideal gases can be found from

\[\Delta u = u_2-u_1=C_v(T_2-T_1)\]

where

\[u\]

\[T\]

\[C_v\]

The above equation provides a convenient way for estimating  of ideal gases in a process. Its accuracy depends on the change in temperature in a process. In many cases, especially, those with small temperature variations, this method is reasonably accurate and can be used for ideal gases when the thermodynamic tables are not available. If the thermodynamic tables are available or high accuracy is required for the process analysis, it is preferable to use the thermodynamic tables to determine

of ideal gases in a process. Its accuracy depends on the change in temperature in a process. In many cases, especially, those with small temperature variations, this method is reasonably accurate and can be used for ideal gases when the thermodynamic tables are not available. If the thermodynamic tables are available or high accuracy is required for the process analysis, it is preferable to use the thermodynamic tables to determine  at different states first, and then

at different states first, and then  .

.

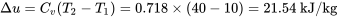

Two kilograms of air is heated from 10oC to 40oC. Calculate the change in internal energy,  , in this process. Will your answer be different if the process is isochoric or isobaric?

, in this process. Will your answer be different if the process is isochoric or isobaric?

Solution

Air is treated as an ideal gas. From Table G1:  ; therefore,

; therefore,

\[\Delta U = m \Delta u=2 \times 21.54 = 43.08\ \rm{kJ}\]

The change in internal energy in this process is 43.08 kJ. As  is a property of the substance (e.g., air in this example), the answer will be the same regardless of the type of the process.

is a property of the substance (e.g., air in this example), the answer will be the same regardless of the type of the process.

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)