4.4: Work

- Page ID

- 88841

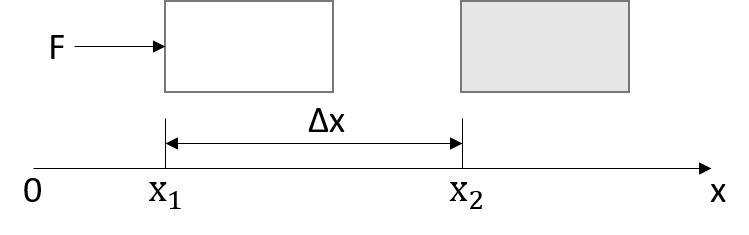

Work is a form of mechanical energy associated with a force and its resulting displacement. When a force  moves a body from one position to another, it does work on that body over the distance, see Figure 4.3.1.

moves a body from one position to another, it does work on that body over the distance, see Figure 4.3.1.

\[{}_{1}W_{2}= \displaystyle\int_{1}^{2}{Fdx }\]

The common SI units for work are kJ and J.

4.3.1 Boundary work

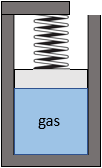

Work associated with the expansion and compression of a gas is commonly called boundary work because it is done at the boundary between a system and its surroundings.

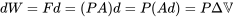

Let us consider a piston-cylinder device, as illustrated in Figure 4.3.2. The gas in the cylinder exerts an upward force,  , where

, where  is the gas pressure, and

is the gas pressure, and  is the cross-sectional area of the piston. Upon receiving heat, the gas will tend to expand, pushing the piston up. We will assume the expansion process is quasi-equilibrium, and the piston moves up an infinitesimal distance

is the cross-sectional area of the piston. Upon receiving heat, the gas will tend to expand, pushing the piston up. We will assume the expansion process is quasi-equilibrium, and the piston moves up an infinitesimal distance  . The boundary work done by the gas to the surroundings in this infinitesimal process is

. The boundary work done by the gas to the surroundings in this infinitesimal process is  ; therefore, the total boundary work between two states in a process can be written as

; therefore, the total boundary work between two states in a process can be written as

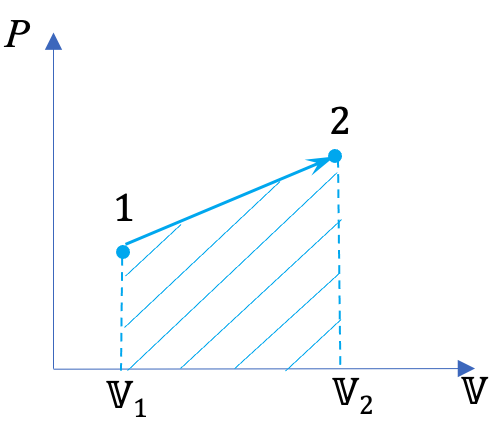

\[{}_{1}W_{2}= \displaystyle\int_{1}^{2}{Pd\mathbb{V}\ }\]

where

\[P\]

\[\mathbb{V}\]

\[{}_{1}W_{2}\]

Specific boundary work refers to the boundary work done by a unit mass of a substance. It can be written as

\[{}_{1}w_{2}=\displaystyle\int_{1}^{2}{Pdv\ }\]

where

\[P\]

\[v\]

\[{}_{1}w_{2}\]

From the integral equations for  and

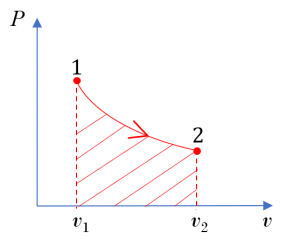

and  , we can tell that the boundary work and specific boundary work between any two states in a process can be illustrated graphically as the area under the process curve in the

, we can tell that the boundary work and specific boundary work between any two states in a process can be illustrated graphically as the area under the process curve in the  and

and  diagrams, respectively. For example, the shaded area in Figure 4.3.3 represents the specific boundary work between states 1 and 2 in the compression process A. The three compression processes, A, B, and C in Figure 4.3.3 have different specific boundary work because of their different paths. By comparing the areas under the process curves, we can tell that process A has the smallest specific boundary work and process C has the largest specific boundary work.

diagrams, respectively. For example, the shaded area in Figure 4.3.3 represents the specific boundary work between states 1 and 2 in the compression process A. The three compression processes, A, B, and C in Figure 4.3.3 have different specific boundary work because of their different paths. By comparing the areas under the process curves, we can tell that process A has the smallest specific boundary work and process C has the largest specific boundary work.

Figure 4.3.3 demonstrates that the boundary work and specific boundary work in a quasi-equilibrium process are path functions; they depend on the initial and final states as well as the process path. Boundary work can be defined as positive or negative. Here is a common sign convention: the boundary work in an expansion process is positive. This is because the change of volume in an expansion process is positive. Likewise, the boundary work in a compression process is negative.

Example 1

Consider a rigid sealed tank of a volume of 0.3 m3 containing nitrogen at 10oC and 150 kPa. The tank is heated until the temperature of the nitrogen reaches 50oC. Treat nitrogen as an ideal gas.

- Sketch the process on a

diagram

diagram - Calculate the boundary work in this process

- Calculate the change in internal energy in this process

Solution

1.  diagram

diagram

2. The boundary work is zero because the volume of nitrogen remains constant in the process.

\[{}_{1}W_{2}=\displaystyle \int_{1}^{2}{Pd\mathbb{V}\ }=0\]

3. Change in internal energy in the process

From Table G1:

R=0.2968 kJ/kgK and Cv= 0.743 kJ/kgK

The mass of nitrogen:

\[\because P\mathbb{V} = mRT\]

\[\therefore m = \dfrac{P\mathbb{V}}{RT} = \dfrac{150 \times 0.3}{0.2968 \times (273.15 + 10)} = 0.5355 \ \rm{kg}\]

The change in internal energy:

\[\begin{align*} \Delta U &= m \Delta u =mC_v\left(T_2-T_1\right) \\&= 0.5355 \times 0.743 \times (50-10) = 15.9 \ \rm{kJ} \end{align*}\]

Nitrogen absorbs 15.9 kJ of heat in this process.

Example 2

Consider 0.2 kg of ammonia in a reciprocating compressor (piston-cylinder device) undergoing an isobaric expansion. The initial and final temperatures of the ammonia are 0oC and 30oC, respectively. The pressure remains 100 kPa in the process.

- Sketch the process on a

diagram

diagram - Calculate the boundary work in this process

- Calculate the change in internal energy in this process

Solution:

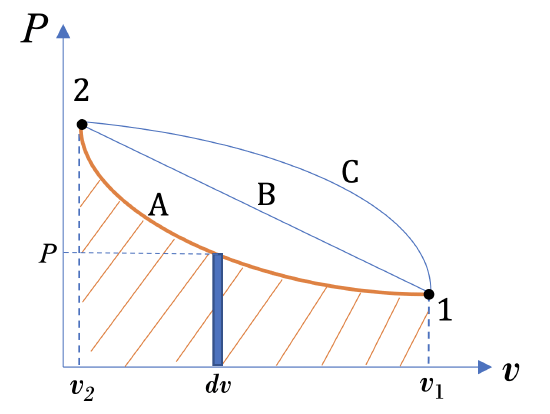

1.  diagram

diagram

2. Boundary work

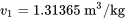

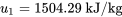

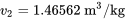

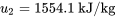

From Table B2: for the initial state 1 at T = 0oC, P = 100 kPa,

For the final state 2 at T = 30oC, P = 100 kPa,

Graphically, the specific boundary work is the shaded rectangular area under the process line in the P –  diagram.

diagram.

\[\begin{align*} {}_{1}W_{2} &=m{}_{1}w_{2} = m\displaystyle\int_{1}^{2}{Pdv} = mP(v_2 - v_1) \\&= 0.2 \times 100 \times (1.46562 - 1.31365) = 3.0394 \ \rm{kJ} \end{align*}\]

3. Change in internal energy

\[\begin{align*} \Delta U &= m \Delta u = m(u_2 - u_1) \\&= 0.2 \times (1554.1 -1504.29)= 9.962 \ \rm{kJ} \end{align*}\]

Example 3

Consider air undergoing an isothermal expansion. The initial and final pressures of the air are 200 kPa and 100 kPa respectively. The temperature of the air remains 50oC in the process. Treat air as an ideal gas.

- Sketch the process on a

diagram

diagram - Calculate the specific boundary work in this process

- Calculate the change in specific internal energy in this process

Solution:

1.  diagram

diagram

2. Specific Boundary work

From Table G1: R = 0.287 kJ/kgK for air. The ideal gas, air, undergoes an isothermal process.

\[\because Pv = RT\]

\[\therefore P=\dfrac{RT}{v}\]

\[\begin{align*} {}_{1}W_{2}&=\displaystyle \int_{1}^{2}{Pdv} = \int_{1}^{2}{\dfrac{RT}{v }dv} \\&= RT\displaystyle\int_{1}^{2}{\dfrac{1}{v }dv} = RT ln\dfrac{v_2}{v_1} = RTln\dfrac{P_1}{P_2} \\&= 0.287 \times (273.15 + 50)ln\dfrac{200}{100} = 64.285 \ \rm{kJ} \end{align*}\]

3. The process is isothermal; therefore, the temperature remains constant and the change in internal energy is zero.

\[\Delta u =C_v\left(T_2-T_1\right)=0\]

4.3.2 Polytropic process and its boundary work

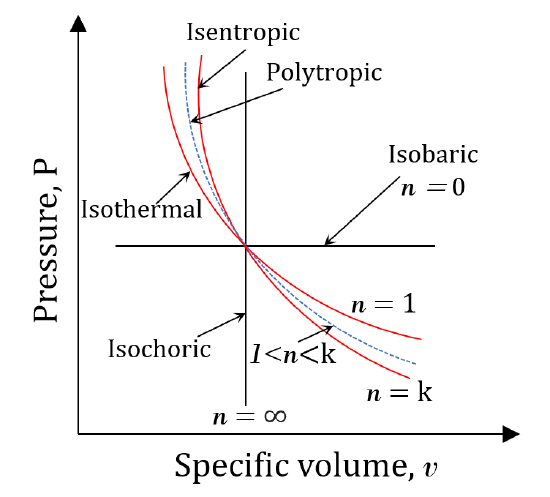

A polytropic process refers to any quasi-equilibrium thermodynamic process, which can be described with the following mathematical expression.

\[P\mathbb{V}^n= \rm{constant}\]

where

\[P\]

\[\mathbb{V}\]

\[v\]

\[n\]

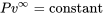

By adjusting  to different values, the above two simple expressions can be used to represent the relations of pressure-volume or pressure-specific volume of various processes that are encountered in real thermal systems, including the isobaric, isochoric, and isothermal processes. Table 4.3.1 lists the polytropic exponents corresponding to an ideal gas undergoing an isobaric, isochoric, and isothermal process, respectively.

to different values, the above two simple expressions can be used to represent the relations of pressure-volume or pressure-specific volume of various processes that are encountered in real thermal systems, including the isobaric, isochoric, and isothermal processes. Table 4.3.1 lists the polytropic exponents corresponding to an ideal gas undergoing an isobaric, isochoric, and isothermal process, respectively.

| Process | Polytropic exponent | Ideal gas equation of state | Polytropic relation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isobaric |  |

|

|

| Isothermal |  |

and and

\[\therefore Pv= \rm{constant}\] |

|

| Isochoric |  |

|

|

Figure 4.3.4 shows different polytropic processes of an ideal gas. In many actual thermodynamic processes, the polytropic exponents are typically in the range of  , where

, where  .

.  and

and  are the constant-pressure and constant-volume specific heats, respectively.

are the constant-pressure and constant-volume specific heats, respectively.

The boundary work and corresponding specific boundary work in a polytropic process can be calculated by using the following equations. Detailed derivations are left for the readers to practice.

The following expressions are valid for both real and ideal gases.

If  ,

,

\[{}_{1}W_{2}=\displaystyle\frac

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[4]/span, line 1, column 2

\[\ {}_{1}w_{2}=\displaystyle\frac

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[5]/span, line 1, column 2

If

\[{}_{1}W_{2}={P}_\mathbf{1}\mathbb{V}_\mathbf{1}{ln}{\displaystyle\frac{\mathbb{V}_\mathbf{2}}{\mathbb{V}_\mathbf{1}}}={P}_\mathbf{2}\mathbb{V}_\mathbf{2}{ln}{\displaystyle\frac{\mathbb{V}_\mathbf{2}}{\mathbb{V}_\mathbf{1}}}\\ \]

\[{}_{1}W_{2}={P}_\mathbf{1}\mathbb{V}_\mathbf{1}{ln}{\displaystyle\frac

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[8]/span[1], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[8]/span[2], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[8]/span[3], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[8]/span[4], line 1, column 2

\[\ {}_{1}w_{2}={P}_\mathbf{1}{v}_\mathbf{1}{ln}{\displaystyle\frac

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[9]/span[1], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[9]/span[2], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[9]/span[3], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[9]/span[4], line 1, column 2

\[\ {}_{1}w_{2}={P}_\mathbf{1}{v}_\mathbf{1}{ln}{\displaystyle\frac

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[10]/span[1], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[10]/span[2], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[10]/span[3], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/div[1]/p[10]/span[4], line 1, column 2

The following two expressions are valid only for ideal gases in an isothermal process ( ).

).

If

\[\ {}_{1}W_{2}=

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[12]/span[1], line 1, column 1

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[12]/span[2], line 1, column 1

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[12]/span[3], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[12]/span[4], line 1, column 2

\[\ {}_{1}w_{2}=

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[13]/span[1], line 1, column 1

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[13]/span[2], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[13]/span[3], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[13]/span[4], line 1, column 1

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[13]/span[5], line 1, column 2

Callstack:

at (Bookshelves/Mechanical_Engineering/Introduction_to_Engineering_Thermodynamics_(Yan)/04:_The_First_Law_of_Thermodynamics_for_Closed_Systems/4.04:_Work), /content/body/div[5]/p[13]/span[6], line 1, column 2

where

\[{}_{1}W_{2}\]

\[{}_{1}w_{2}\]

\[P\]

\[\mathbb{V}\]

\[v\]

\[T\]

\[R\]

\[m\]

Example 4

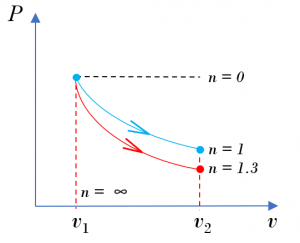

Consider an ideal gas undergoing a polytropic process. At the initial state: P1=200 kPa, v1=0.05 m3/kg. At the final state: v2=0.1 m3/kg. For n=1.3 and n=1,

- Sketch the two processes on a

diagram. Which process has a larger specific boundary work?

diagram. Which process has a larger specific boundary work? - Calculate the specific boundary work and verify your answer to the question in part 1.

Solution:

1.  diagram

diagram

From the  diagram, the area under the process line for

diagram, the area under the process line for  is greater than that for

is greater than that for  ; therefore, the isothermal process with

; therefore, the isothermal process with  has a larger specific boundary work.

has a larger specific boundary work.

2. For  , find the final pressure

, find the final pressure  first.

first.

\[\because P_1v_1^n = P_2v_2^n\]

\[\therefore P_2 = P_1\left(\dfrac {v_1}{v_2}\right)^n = 200 \times \left(\dfrac{0.05}{0.1}\right)^{1.3} = 81.225 \ \rm{kPa}\]

For  , the process is isothermal; therefore,

, the process is isothermal; therefore,

Compare the specific boundary work in these two processes, the isothermal process (n=1) has a larger specific boundary work than the polytropic process with n = 1.3. The calculation results are consistent with the observation from the  diagram.

diagram.

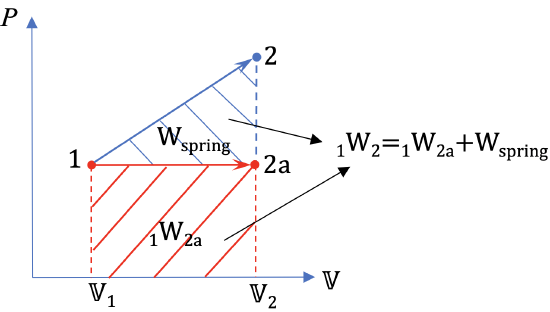

4.3.3 Spring work

Spring work is a form of mechanical energy required to compress or expand a spring to a certain distance, see Figure 4.3.5. Spring force and spring work can be expressed as follows:

\[F=Kx\]

\[W_{spring}=\displaystyle\int_{1}^{2}{Fdx=}\displaystyle\frac{1}{2}K\left(x_2^2-x_1^2\right)\]

where

\[F\]

\[K\]

\[W_{spring}\]

\[x_1\]

Example 5

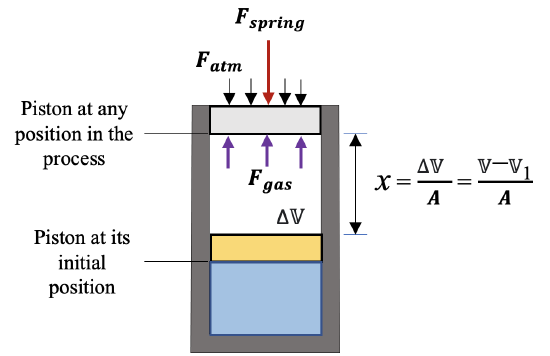

A linear spring with spring constant K=100 kN/m is mounted on a piston-cylinder device. At the initial state, the cylinder contains 0.15 m3 of gas at 100 kPa. The spring is uncompressed. The gas is then heated until its volume expands to 0.2 m3. The piston’s cross-sectional area is 0.1 m2. Assume the piston is frictionless with negligible weight and the process is quasi-equilibrium,

-

- Write an expression of the gas pressure as a function of the gas volume in this process

- Sketch the process on a

diagram

diagram - Calculate the total work done by the gas during this expansion process

- If the spring is not mounted on the piston, the gas in the cylinder will expand isobarically after being heated. To reach the same final volume, 0.2 m3, how much work must be done by the gas in the expansion process?

Figure 4.3.e5 Piston-cylinder device with a spring loaded on top of the piston

Solution:

1. Analyze the forces acting on the piston, see below.

Three forces acting on the piston are in equilibrium.

\[\because\sum F = 0: F_{gas} = F_{spring} + F_{atm}\]

\[\therefore P_{gas} A = Kx + P_{atm} A = K \dfrac{\mathbb{V} -\mathbb{V}_1}{A} + P_{atm} A\]

\[\therefore P_{gas} = \dfrac{K(\mathbb{V}-\mathbb{V}_1)}{A^2} + P_{atm}\]

At the initial state:  . Substitute the two values,

. Substitute the two values,

\[\because 100 = \dfrac{K(\mathbb{V}-\mathbb{V}_1)}{A^2} + P_{atm}\]

\[\therefore P_{atm} = 100 \ \rm{kPa}\]

with K =100 kN/m, A = 0.1 m2, Patm = 100 kPa and  = 0.15 m3, the gas pressure can be expressed as a function of the gas volume.

= 0.15 m3, the gas pressure can be expressed as a function of the gas volume.

\[\because P_{gas} = \dfrac{100(\mathbb{V}-0.15)}{0.1^2} + 100\]

\[\therefore P_{gas} = 10^4 \mathbb{V} -1400\]

where gas pressure is in kPa and  is in m3.

is in m3.

2.  diagram

diagram

From part 1, Pgas is a linear function of volume  .

.

3. During the expansion process, the gas has to overcome the resistance from the springand. At the same time, the gas pressure and volume increase until the gas reaches the final state. The total work done by the gas is the shaded area of the trapezoid in the  diagram.

diagram.

At the final state,  ; therefore,

; therefore,

\[P_{gas,2}= 10^4 \times 0.2 -1400 = 600 \ \rm{kPa}\]

The total work done by the gas is

\[\begin {align*} {}_{1}W_{2} &= \dfrac{(P_{gas,2} + P_{gas,1})(\mathbb{V}_2 - \mathbb{V}_1)}{2} \\&= \dfrac{(600 + 100)(0.2 - 0.15)}{2} = 17.5 \ \rm{kJ} \end{align*}\]

4. If the gas expands isobarically from  = 0.15 m3 to

= 0.15 m3 to  = 0.2 m3, the work done by the gas will be

= 0.2 m3, the work done by the gas will be

\[\begin {align*} {}_{1}W_{2a} &= P_{gas,1} (\mathbb{V}_2 - \mathbb{V}_1) \\&=100 \times (0.2 - 0.15) = 5 \ \rm{kJ} \end{align*}\]

\[{}_{1}W_{2a}\]

\[W_{spring} = {}_{1}W_{2} - {}_{1}W_{2a} = 17.5 -5 = 12.5 \ \rm{kJ}\]

Query \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Query \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Media Attributions

- Boundary work © Kh1604 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Work done by the spring force © Svjo is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license