5.2: Structures

- Page ID

- 111334

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

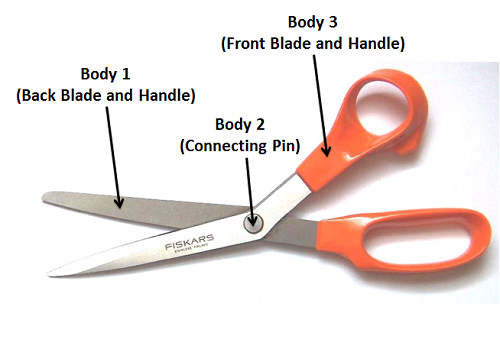

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)An engineering structure is term used to describe any set of interconnected bodies. The different bodies in the structure can move relative to one another (such as the blades in a pair of scissors) or they can be be fixed relative to one another (such as the different beams connected to form a bridge).

When analyzing engineering structures, we will sometimes analyze the structure as a whole, and we will sometimes break the structure down into individual bodies that are analyzed separately. The exact methods used depend upon what unknown forces we are looking for and what type of structure we are analyzing.

Internal and External Forces:

When examining a single body, we would find the forces that this body exerted on surrounding bodies, and the forces that these surrounding bodies would exert on the body we are analyzing. These forces are all considered external forces because they are forces between the body and the external environment.

In an engineering structure, we still have external forces where the structure is interacting with bodies external to the structure, but we also can think about the forces that different parts of the structure exert on one another (the force between the pin and the blade in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), for example). Since both of these bodies are part of the structure we are analyzing, these forces are considered internal forces.

If we only wish to determine the external forces acting on a structure, then we can treat the whole structure as a single body (assuming the structure is rigid as a whole). If we wish to determine the internal forces acting between components in the structure, then we will need to disassemble the structure into separate bodies in our analysis.

Types of Structures:

Another important consideration when analyzing structures is the type of structure that is being analyzed. All structures fall into one of three categories: trusses, frames, or machines. Frames and machines are analyzed in the same way so distinction between them is less important, but the analysis methods used for trusses vary greatly from the analysis methods used for frames and machines, so determining if a structure is a truss or not is an important first step in structure analysis.

Trusses:

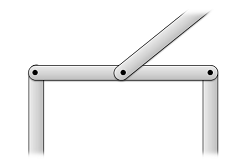

A truss is a structure that consists entirely of two-force members. If any one body in the structure is not a two-force member, then the structure is either a frame or a machine. Also,in order to be a statically determinate truss (a truss where we can actually solve for all the unknowns), the truss must be independently rigid as a whole. If different parts of the truss could move relative to one another then the truss separated is not independently rigid.

A two-force member is a body where forces are applied at only two locations. If forces are applied at more than two locations, or if any moments are applied, then the body is not a two-force member (see the two-force member page for more details). Because of the unique assumptions we can make with two-force members, we can apply two unique methods to the analysis of trusses (the method of joints and the method of sections) that we cannot apply to frames and machines (where we cannot assume we have two-force members).

Trusses can be broken down further into plane trusses and space trusses. A plane truss is a truss where all members lie in a single plane. This means that plane trusses can essentially be treated as two dimensional systems. Space trusses on the other hand have members that are not limited to a single plane. This means that space trusses need to be analyzed as a three dimensional system.

|

|

|

|

Frames and Machines:

A frame or a machine is structure where at least one component of the structure is not a two-force member. This component will be a body in the structure that has forces acting at three or more points on it. This could be three connection points on the body, or it could be two connection points, with a force applied at a third location.

|

|

In terms of the difference between a frame and a machine, a frame is a rigid structure as a whole, while a machine is not rigid. This means that no part can move relative to the other parts in a frame, while parts can move relative to one another in a machine. Though there is a difference in vocabulary in describing frames and machines, they are grouped together here because we use the same process to analyze both of these structures.

Because frames and machines do not consist entirely of two-force members, we cannot make the assumptions that allow us to use the method of joints and the method of sections. For this reason, we need to use a different analysis method (simply called the analysis of frames and machines here).