3.5: Continuous Random Variables and the Probability Density Function

- Page ID

- 47236

Let us suppose now the random event has infinitely many outcomes: for example, the random variable \(x\) occurs anywhere in the range of [0, 1]. Clearly the probability of hitting any specific point is zero (although not impossible). We proceed this way:

\[p(x \, \textrm {is in the range} [x_o, x_o + dx]) = \underline{p}(x_o) dx, \]

where \(\underline{p} (x_o)\) is called the probability density function. Because all the probabilities that comprise it have to add up to one, we have

\[ \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \underline{p}(x) \, dx = 1. \]

With this definition, we can calculate the mean of the variable \(x\) and of a function of the variable, \(f(x)\):

\begin{align} E[x] \, &= \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} x \underline{p}(x) \, dx, \\[4pt] E[f(x)] \, &= \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) \underline{p}(x) \, dx. \end{align}

Here are a few examples.

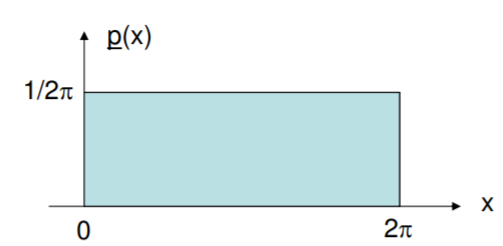

Consider a random variable that is equally likely to occur at any value between zero and \(2\pi\). Considering that the area under \(\underline{p}\) has to be one, we know then that \(\underline{p}(x) = 1/2 \pi\) for \(x = [0, 2 \pi]\) and it is zero everywhere else.

\begin{align*} E(x) &= \pi \\[4pt] \sigma^2 (x) &= \pi^2 /3 \\[4pt] \sigma (x) &= \pi / \sqrt{3} \\[4pt] E \cos (x) &= \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} \dfrac{1}{2\pi} \cos x \, dx = 0 \\[4pt] E \cos ^2 (x) &= \dfrac{1}{2}. \end{align*}

.png?revision=2)

The earlier concept of conditional probability carries over to random variables. For instance, considering this same example we can write

\begin{align*} E[x | x>\pi] &= \int\limits_{0}^{2 \pi} x \underline{p} (x | x>\pi) \, dx \\[4pt] &= \int\limits_{\pi}^{2 \pi} x \dfrac{\underline{p} (x)} {p(x > \pi)} \, dx = \dfrac{3 \pi}{2}. \end{align*}

The denominator in the integral inflates the original pdf by a factor of two, and the limits of integration cause only values of \(x\) in the range of interest to be used.