4.3: Global and Regional Effects of Secondary Pollutants (II)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

What is Known for Certain

Human Activities Change the Earth's Atmosphere

Scientists know for certain that human activities are changing the composition of Earth's atmosphere. Increasing levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, like carbon dioxide (CO2), have been well documented since pre-industrial times. There is no doubt this atmospheric buildup of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases is largely the result of human activities.

It's well accepted by scientists that greenhouse gases trap heat in the Earth's atmosphere and tend to warm the planet. By increasing the levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, human activities are strengthening Earth's natural greenhouse effect. The key greenhouse gases emitted by human activities remain in the atmosphere for periods ranging from decades to centuries.

Additional Information

A warming trend of about 1oF has been recorded since the late 19th century. Warming has occurred in both the northern and southern hemispheres, and over the oceans. Confirmation of twentieth-century global warming is further substantiated by melting glaciers, decreased snow cover in the northern hemisphere, and even warming below ground.

What is Likely but Uncertain

Greenhouse Gases Contribute to Global Warming

Determining to what extent the human-induced accumulation of greenhouse gases since pre-industrial times is responsible for the global warming trend is not easy. This is because other factors, both natural and human, affect our planet's temperature. Scientific understanding of these other factors—most notably natural climatic variations, changes in the sun's energy, and the cooling effects of pollutant aerosols—remains incomplete or uncertain; however…

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated there was a "discernible" human influence on climate; and that the observed warming trend is "unlikely to be entirely natural in origin."

- In the most recent Third Assessment Report (2001), IPCC wrote "There is new and stronger evidence that most of the warming observed over the last 50 years is attributable to human activities."

In short, scientists think rising levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere are contributing to global warming, as would be expected; but to what extent is difficult to determine at the present time.

Additional Information

As atmospheric levels of greenhouse gases continue to rise, scientists estimate average global temperatures will continue to rise as a result. By how much and how fast remain uncertain. IPCC projects further global warming of 2.2 - 10oF (1.4 - 5.8oC) by the year 2100.

Factors Affecting Temperature

Some factors that affect the Earth's temperatures include clouds, fine particles, and oceans.

Clouds

- Low, thick clouds primarily reflect solar radiation and cool the surface of the Earth.

- High, thin clouds primarily transmit incoming solar radiation; at the same time, they trap some of the outgoing infrared radiation emitted by the Earth and radiate it back downward, thereby warming the surface of the Earth.

- Whether a given cloud will heat or cool the surface depends on several factors, including the cloud's height, its size, and the make-up of the particles that form the cloud.

- The balance between the cooling and warming actions of clouds is very close - although, overall, cooling predominates.

Fine Particles (Aerosols) in the Atmosphere

The amount of fine particles or aerosols in the air has a direct effect on the amount of solar radiation hitting the Earth's surface. Aerosols may have significant local or regional impact on temperature.

Atmospheric factors shown in the image below include natural factors such as clouds, volcanic eruptions, natural biomass (forest) burning, and dust from storms. In addition, human-induced factors such as biomass burning (forest and agricultural fires) and sulfate aerosols from burning coal add tiny particles that contribute to cooling, as detailed in the following video.

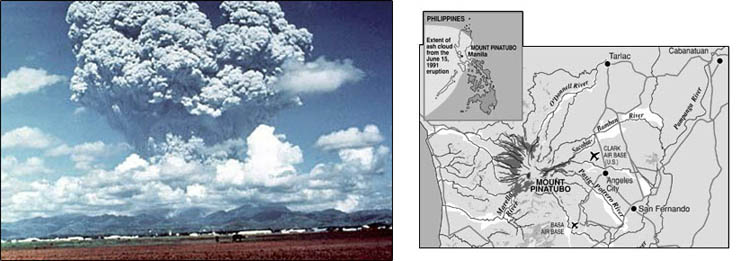

When Mount Pinatubo erupted in the Philippines in 1991, an estimated 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide and ash particles blasted more than 12 miles high into the atmosphere. The eruption caused widespread destruction and human causalities. Gases and solids injected into the stratosphere circled the globe for three weeks.

Volcanic eruptions of this magnitude can impact global climate, reducing the amount of solar radiation reaching the Earth's surface, lowering temperatures in the troposphere, and changing atmospheric circulation patterns. The extent to which this occurs is an uncertainty.

Figure 4.3.1 shows a picture of Mount Pinatubo next to a map of its location and how far the ash from its eruption spread.

Figure 4.3.1. Mount Pinatubo erupting (left) and a map of its location and how far the ash from its eruption spread (right)

Additional Information

Water vapor is a greenhouse gas, but at the same time, the upper white surface of clouds reflects solar radiation back into space. Albedo—reflections of solar radiation from surfaces on the Earth—creates difficulties in exact calculations. If, for example, the polar icecap melts, the albedo will be significantly reduced. Open water absorbs heat, while white ice and snow reflect it.

Oceans

Oceans play a vital role in the energy balance of the Earth. It is known that the top 10 feet of the oceans can hold as much of the heat as the entire atmosphere above the surface. However, most of the incoming energy is incident on the equatorial region.

The water in the oceans in the equatorial regions is warmer and needs to be transported to the northern latitudes. This is done due to natural variations in the temperatures of the water and prevailing winds that cause the disturbances in the surface waters.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that even the low end of this warming projection "would probably be greater than any seen in the last 10,000 years, but the actual annual to decadal changes would include considerable natural variability."

The following video explains the ocean conveyor belt.

Impact of Global Warming

Impact of Global Warming on such things as health, water resources, polar regions, coastal zones, and forests is likely but it is uncertain to what extent.

Health

The most direct effect of climate change would be the impacts of the hotter temperatures, themselves. Extremely hot temperatures increase the number of people who die on a given day for many reasons:

- People with heart problems are vulnerable because one's cardiovascular system must work harder to keep the body cool during hot weather.

- Heat exhaustion and some respiratory problems increase.

- Higher air temperatures also increase the concentration of ozone at ground level.

- Diseases that are spread by mosquitoes and other insects could become more prevalent if warmer temperatures enabled those insects to become established farther north; such "vector-borne" diseases include malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, and encephalitis.

Water Resources

Changing climate is expected to increase both evaporation and precipitation in most areas of the United States. In those areas where evaporation increases more than precipitation, soil will become drier, lake levels will drop, and rivers will carry less water. Lower river flows and lower lake levels could impair navigation, hydroelectric power generation, and water quality, and reduce the supplies of water available for agricultural, residential, and industrial uses. Some areas may experience increased flooding during winter and spring, as well as lower supplies during summer.

Polar Regions

Climate models indicate that global warming will be felt most acutely at high latitudes, especially in the Arctic where reductions in sea ice and snow cover are expected to lead to the greatest relative temperature increases. Ice and snow cool the climate by reflecting solar energy back to space, so a reduction in their extent would lead to greater warming in the region.

Coastal Zones

Sea level is rising more rapidly along the U.S. coast than worldwide. Studies by EPA and others have estimated that along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, a one-foot (30 cm) rise in sea level is likely by 2050.

In the next century, a two-foot rise is most likely, but a four-foot rise is possible. Rising sea level inundates wetlands and other low-lying lands, erodes beaches, intensifies flooding, and increases the salinity of rivers, bays, and groundwater tables. Low-lying countries like Maldives located in the Indian Ocean and Bangladesh may be severely affected. The world may see global warming refugees from these impacts.

Forests

The projected 2°C (3.6°F) warming could shift the ideal range for many North American forest species by about 300 km (200 mi.) to the north.

- If the climate changes slowly enough, warmer temperatures may enable the trees to colonize north into areas that are currently too cold, at about the same rate as southern areas became too hot and dry for the species to survive. If the Earth warms 2°C (3.6°F) in 100 years, however, the species would have to migrate about 2 miles every year.

- Poor soils may also limit the rate at which tree species can spread north.

- Several other impacts associated with changing climate further complicate the picture:

- On the positive side, CO2 has a beneficial fertilization effect on plants, and also enables plants to use water more efficiently. These effects might enable some species to resist the adverse effects of warmer temperatures or drier soils.

- On the negative side, forest fires are likely to become more frequent and severe if soils become drier.

What is Uncertain

The Long Term Effects of Global Warming

Scientists have identified that our health, agriculture, water resources, forests, wildlife, and coastal areas are vulnerable to the changes that global warming may bring. But projecting what the exact impacts will be over the twenty-first century remains very difficult. This is especially true when one asks how a local region will be affected.

Scientists are more confident about their projections for large-scale areas (e.g., global temperature and precipitation change, average sea level rise) and less confident about the ones for small-scale areas (e.g., local temperature and precipitation changes, altered weather patterns, soil moisture changes). This is largely because the computer models used to forecast global climate change are still ill-equipped to simulate how things may change at smaller scales.

Some of the largest uncertainties are associated with events that pose the greatest risk to human societies. IPCC cautions, "Complex systems, such as the climate system, can respond in non-linear ways and produce surprises." There is the possibility that a warmer world could lead to more frequent and intense storms, including hurricanes. Preliminary evidence suggests that, once hurricanes do form, they will be stronger if the oceans are warmer due to global warming. However, the jury is still out whether or not hurricanes and other storms will become more frequent.

Fun Fact

IPCC stands for Intergovernmental Panel on Climate change. Its role is to assess scientific, technical and socio-economic information to determine the risk of human-induced climate change and the options available for adapting to these changes.

Solutions for Global Warming

Today, there is no single solution that is agreed upon, because scientists are still debating whether the problem is a real one or a perceived one. The main question is whether we want to wait to see the effects for sure and then act, or whether we want to start to do something now?

Like many pioneer fields of research, the current state of global warming science can't always provide definitive answers to our questions. There is certainty that human activities are rapidly adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, and that these gases tend to warm our planet. This is the basis for concern about global warming.

The fundamental scientific uncertainties are these: How much more warming will occur? How fast will this warming occur? And what are the potential adverse and beneficial effects? These uncertainties will be with us for some time, perhaps decades.

Global warming poses real risks. The exact nature of these risks remains uncertain. Ultimately, this is why we have to use our best judgment—guided by the current state of science—to determine what the most appropriate response to global warming should be.

What Difference Can I Make?

When faced with this question, individuals should recognize that, collectively, they can make a difference. In some cases, it only takes a little change in lifestyle and behavior to make some big changes in greenhouse gas reductions. For other types of actions, the changes are more significant.

When that action is multiplied by the 270 million people in the U.S. or the 6 billion people worldwide, the savings are significant. The actions include being energy efficient in the house, in the yard, in the car, and in the store.

Everyone's contribution counts, so why not do your share?

Note

Energy efficiency means doing the same (or more) with less energy. When individual action is multiplied by the 270 million people in the U.S., or the 6 billion people worldwide, the savings can be significant.

How Can I Save the Environment?

You can help save the environment by making changes from the top to the bottom of your home.

These are the things you can do in your home – from top to bottom - to protect from the environment:

- Purchase "Green Power" - electricity that is generated from renewable sources such as solar, wind, geothermal, or biomass - for your home's electricity, if available from your utility company. Although the cost may be slightly higher, you'll know that you are buying power from an environmentally friendly energy source.

- Insulate your home – you’ll learn more about this in Home Activity Three.

- Use low-flow faucets in your showers and sinks.

- Replace toilets with water-saving lavatories.

- Purchase home products—appliances, new home computers, copiers, fax machines, that display the ENERGY STAR® label - You can reduce your energy consumption by up to 30 percent and lower your utility bills! Remember, the average house is responsible for more air pollution and carbon dioxide emissions than is the average car.

- When your lights burn out, replace them with energy-efficient compact fluorescent lights.

- Lower the temperature on your hot water tank to 120 degrees.

- Tune up your furnace.

- Insulate your water heater and all water pipes to reduce heat loss.

When you remodel, build, or buy a new home, incorporate all of these energy efficiency measures—and others.

Important Point

Each of us, in the U.S., contributes about 22 tons of carbon dioxide emissions per year, whereas the world average per capita is about 6 tons.

The good news is that there are many ways you and your family can help reduce carbon dioxide pollution and improve the environment for you and your children