Debye Model For Specific Heat

- Page ID

- 311

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Debye model is a method developed by Peter Debye in 1912\(^{[7]}\) for estimating the phonon contribution to the specific heat (heat capacity) in a solid\(^{[1]}\). This model correctly explains the low temperature dependence of the heat capacity, which is proportional to \(T^3\) and also recovers the Dulong-Petit law at high temperatures. However, due to simplifying assumptions, its accuracy suffers at intermediate temperatures.

Introduction to Phonons

In 1912 Debye realized that, inconsistent with the Einstein model, low-energetic excitations of a solid material were not oscillations of a single atom\(^{[2]}\), but collective modes propagating through the material. Such vibrations can be considered to be sound waves, and their propagation speed is the speed of sound in the material\(^{[3]}\). Moreover, these modes only accept energy in discreet amounts.

Quantum theory uses the concepts of phonons, which are “quasi-particles” with definite energies and directions of motion, to treat the vibrations. The concept of phonon is analogous with photons of the electromagnetic wave. The relations between the energy of a phonon \(\varepsilon\), the angular frequency \(\omega\) and the wave vector \(\vec{q}\) are:

\[ \begin{align} \varepsilon=\hbar\omega \end{align} \label{1}\]

\[ \begin{align} \omega=\upsilon_{s}|\vec{q}| \end{align} \label{2}\]

where \(v_s\) is the velocity of the sound wave.

Phonons obey Bose–Einstein statistics. The expectation number of bosons in a state with energy \(E\) is\(^{[6]}\):

\[ \begin{align} n_{E}=\dfrac{1}{e^{E/k_{B}T}-1}=\dfrac{1}{e^{\hbar\omega/k_{B}T}-1} \end{align} \label{3}\]

where \(k_B\)= 1.380 6504(24)×10−23J/K is the Boltzmann constant.

Debye frequency and Debye Temperature

Unlike electromagnetic radiation in a box, a phonon cannot have infinite frequency. Its frequency is bound by the medium of its propagation — the atomic lattice of the solid. If there are N primitive cells in the specimen, the total number of phonon modes are N. A cut-off frequency \({\omega}_D\), known as Debye frequency, is determined by the following manner\(^{[4]}\):

In the 3 dimensional reciprocal space, the volume for each allowed wave vector \(\vec{q}\) is:

\[ \begin{align} \left(\dfrac{2\pi}{L}\right)^{3}=\dfrac{8\pi^{3}}{V} \end{align} \label{4}\]

Since there is a cut-off wave vector \(q_{D}={\omega}_{D}/{\upsilon_{s}}\), all the modes are confined within a sphere with radius \(q_D\). Thus number of modes (not number of phonons) should be (5)

\[ \begin{align} N=\left(\dfrac{4}{3}\pi{q_{D}}^{3})/({\dfrac{8\pi^{3}}{V}}\right) \end{align} \label{5}\]

or

\[ \begin{align} q_{D}=\left(6\pi^{2}\dfrac{N}{V}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}} \end{align} \label{6}\]

\[ \begin{align} \omega_{D}=\upsilon_{s}\left(6\pi^{2}\dfrac{N}{V}\right)^{\frac{1}{3}} \end{align} \label{7}\]

Debye temperature \(T_{D}\) is defined as

\[\begin{align} T_{D}=\dfrac{\hbar\omega_{D}}{k_{B}}=\dfrac{\hbar\upsilon_{s}}{k_{B}}(6\pi^{2}\dfrac{N}{V})^{\frac{1}{3}} \end{align} \label{8}\]

The significance of this physical term will be discussed below. For elements in the same group, heavier atoms have lower Debye temperatures, simply because the velocity of sound decreases as the density increases.\(^{[4]}\) The Debye temperatures of several substances are listed in Table 1.\(^{[1]}\)

| Aluminum | 428K | Iron | 470K | Silicon | 645K | Tungsten | 400K |

| Cadmium | 209K | Lead | 105K | Silver | 225K | Zinc | 327K |

| Chromium | 630K | Manganese | 410K | Tantalum | 240K | Carbon | 2230K |

| Copper | 343.5K | Nickel | 450K | Tin(white) | 200K | Ice | 192K |

| Gold | 165K | Platinum | 240K | Titanium | 420K |

Heavier atoms have lower Debye temperatures, because the velocity of sound decreases as the density increases.

Derivation for Specific Heat

In the Debye approximation, the velocity of sound \(\upsilon_{s}\) is taken as constant for each polarization type, as it would be for a classical elastic continuum. According to equation (7), the density of states is:

\[ \begin{align} D_{(\omega)} =\dfrac{dN}{d\omega}=\dfrac{V\omega^{2}}{2\pi^{2}\upsilon_{s}^{3}} \end{align} \label{9}\]

Thus, thermal energy for each polarization type is given by\(^{[4]}\):

\[ \begin{align} U=\int d\omega D(\omega) n(\omega)\hbar\omega=\int_{0}^{\omega_{D}}d\omega\dfrac{V\omega^{2}}{2\pi^{2}\upsilon_{s}^{3}}\dfrac{\hbar\omega}{e^{\hbar\omega/k_{B}T}-1} \end{align} \label{10}\]

\[ \begin{align} U=\dfrac{3V\hbar}{2\pi^{2}\upsilon_{s}^{3}}\int_{0}^{\omega_{D}}d\omega\dfrac{\omega^{3}}{e^{\hbar\omega/k_{B}T}-1}=\dfrac{3Vk_{B}^{4}T^{4}}{2\pi^{2}\upsilon_{s}^{3}\hbar^{3}}\int_{0}^{x_{D}}dx\dfrac{x^{3}}{e^{x}-1}=9Nk_{B}T(\dfrac{T}{T_{D}})^{3}\int_{0}^{x_{D}}dx\dfrac{x^{3}}{e^{x}-1} \end{align} \label{11}\]

where \(x=\hbar\omega/k_{B}T\) and \(x_{D}\equiv T_{D}/T\).

The heat capacity is:

\[ \begin{align} C_{V}=\dfrac{\partial U}{\partial T}=9Nk_{B}(\dfrac{T}{T_{D}})^{3}\int_{0}^{x_{D}}dx\dfrac{x^{4}e^{x}}{(e^{x}-1)^{2}} \end{align} \label{12}\]

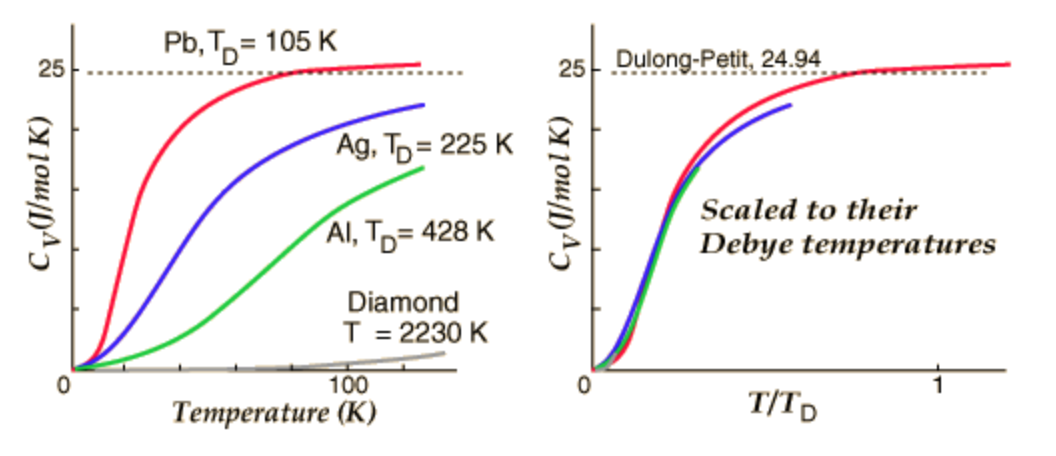

At the left of Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)\(^{[3]}\) below, the experimental results of specific heats of four substances are plotted as a function of temperature and they look very different. But if they are scaled to \(T/T_{D}\), they look very similar and are very close to the Debye theory.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Specific Heats of Lead, Silver, Aluminum and Diamond

High and Low Temperature Limits

The integral in Equation (12) cannot be evaluated in closed form. But the high and low temperature limits can be assessed.

High Temperature Limit

For the high temperature case where \(T\gg T_{D}\), the value of \(x\) is very small throughout the range of the integral. This justifies using the approximation to the exponential \(e^x \approx 1 + x\) and reduces equation (11) and (12) to

\[\begin{align} U=9Nk_{B}T \left(\dfrac{T}{T_{D}} \right)^{3}\int_{0}^{x_{D}}x^{2}dx=3Nk_{B}T \end{align} \label{14}\]

\[ \begin{equation} C_{V}=3Nk_{B} \end{equation} \label{13}\]

which is the classical Dulong-Petit result.

When the temperature is above the Debye temperature, the heat capacity is very close to the classical value \(3Nk_{B} T\). For temperatures below the Debye temperature, quantum effects become important and \(C_v\) decreases to zero. Note that diamond, with a Debye temperature of 1860K, is a “quantum solid” at room temperature. \(^{[8]}\)

Low Temperature Limit

At very low temperature where \(T\ll T_{D}\), only long wavelength acoustic modes are thermally excited. These are just the modes that can be treated as elastic continuum with macroscopic elastic constants. The energy of those short wavelength modes are too high to be populated significantly at low temperatures. We may approximate \(x_D\equiv T_{D}/T\) to infinity and make use of the standard integral

\[ \begin{align} \int_{0}^{\infty}dx\dfrac{x^{3}}{e^{x}-1}=\dfrac{\pi^{4}}{15} \end{align} \label{15}\]

to obtain

\[ \begin{align} U=\dfrac{3\pi^{4}Nk_{B}T^{4}}{5T_{D}^{3}} \end{align} \label{16}\]

\[ \begin{align} C_{V}=\dfrac{12\pi^{4}Nk_{B}T^{3}}{5T_{D}^{3}}\cong324Nk_{B}\dfrac{T^{3}}{T_{D}^{3}} \end{align} \label{17}\]

For actual crystals, the temperatures at which the \(T^3\) approximation holds are quite low, even may be below \(T_D/50\). It is easy to understand \({T/T_D}^3\) with a simple argument. Only the modes with \(\hbar\omega<k_{B}T\) will be excited to any appreciable extent at a low temperature T. Define \(\omega_{T}\equiv kT/\hbar\) as the largest frequency excited at this temperature. In the reciprocal space, the fraction occupied by the excited states is \({(q_{T}/q_{D})}^3\) or \({(w_{T}/w_{D})}^3={(T/T_{D})}^3\).

Extension: Einstein-Debye Specific Heat

This \(T\) dependence of the specific heat at very low temperatures agrees with experiment for nonmetals. For metals the specific heat of highly mobile conduction electrons is approximated by Einstein Model, which is composed of single-frequency quantum harmonic oscillators. The temperature dependence of Einstein model is just T. It becomes significant at low temperatures and is combined with the above lattice specific heat in the Einstein-Debye specific heat\(^{[3]}\).

\[ \begin{align} C_{metal}=C_{electron}+C_{phonon}=\dfrac{\pi^{2}Nk^{2}}{2E_{f}}T+\dfrac{12\pi^{4}Nk_{B}}{5T_{D}^{3}}T^{3} \end{align} \label{18}\]

Finally, experiments suggest that amorphous materials do not follow the Debye \(T^3\) law even at temperatures below 0.01\(T_{D}\)\(^{[8]}\). There is more yet to be learned.

References

- http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Debye_model

- http://www.uam.es/personal_pdi/cienc...ivos/debye.pdf

- http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu...ds/phonon.html

- C. Kittel, introduction to solid state physics, pp.117-140. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1996

- L. Landau and E. Lifshitz, Statistical Physics, Part, pp.191 -217. Elsevier, 1984

- http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Bose%E2...ein_statistics

- Zur Theorie der spezifischen Waerm, Annalen der Physik (Leipzig) 39(4)

- www.phys.unsw.edu.au/~gary/SM3_6.pdf

Contributors and Attributions

ContribMSE5317